|

||||||

| Forest Resources Home | News | Make a Gift | UW Alumni | ||||||

|

April 2011 | Return to issue home

Crows & Humans: Evolving Together

Professor John Marzluff has long been fascinated by the amazing feats of crows and ravens and has wondered about the ways in which they have adapted and evolved in their ongoing cohabitation with humans. Marzluff is blending biology, conservation and anthropology to understand if and how human and animal cultures have co-evolved, and in the process has made some surprising discoveries. Marzluff’s graduate (Northern Arizona University) and initial postdoctoral (University of Vermont) research focused on the social behavior and ecology of jays and ravens. He was especially interested in communication, social organization and foraging behavior. His post-doctoral work took him to Maine where he worked with Bernd Heinrich studying raven winter ecology. Marzluff, his wife, Colleen, and their team of sled dogs then moved to Boise, Idaho where he led studies on ravens of Greenland and Idaho and developed techniques for the captive breeding and reintroduction of the critically endangered Hawaiian crow. Marzluff has authored more than 100 scientific papers on various aspects of bird behavior and wildlife management. He is currently leader of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Recovery Team for the critically endangered Mariana Crow and a Fellow of the American Ornithologist's Union.His current research at the UW, where he has been on the faculty since 1997, brings a behavioral approach to pressing conservation issues including raptor management, management of pest species and assessment of nest predation. His studies have included the effects of military training on falcons and eagles in southwestern Idaho; the effects of timber harvest, recreation and forest fragmentation on goshawks and marbled murrelets in western Washington and Oregon; conservation strategies for Pacific Island crows; the effects of urbanization on songbirds in the Seattle area and the ecology and evolution of crows, ravens and jays. His recent research has included innovative studies on human face recognition in crows. For 20 years Marzluff often wondered if some of the birds in his studies could identify the researchers who trapped and banded them as part of the research—previously trapped birds seemed more wary of particular scientists and were sometimes harder to catch. He decided to test his suspicions directly in an ingenious project involving mask-wearing researchers and volunteers on the UW campus. The project is described in a New York Times article, “Friend or Foe? Crows Never Forget a Face, It Seems” and was published as an article, “Lasting recognition of threatening people by wild American crows,” in the journal Animal Behaviour. Though this is the first formal study of human face recognition in wild birds, its findings confirm the suspicions of many other researchers who have observed similar abilities in crows, ravens, gulls and other species. Collaborating with researchers in UW’s Department of Radiology, Marzluff is now peering into the brain of the crow to determine what parts of the brain enable crows to recognize dangers, including those posed by humans.

For the past 10 years, Marzluff and his students have surveyed birds on the urban fringes of Seattle. They count birds, monitor nests, record behavior and catch and band birds to track survival rates. Marzluff became interested in how urban sprawl affects bird populations immediately after moving from Boise to the Seattle area. He says, "Moving here, it was obvious that urbanization was the major issue for biodiversity in western Washington. Urbanization reduces, converts, perforates and fragments native vegetation. But it also provides food, water and shelter for birds; surprisingly, in some cases suburban sprawl can actually increase biodiversity. In the wildlife science courses I teach, I review some of these processes at national and global scales and how they affect bird demography, relative abundance and community composition in the Seattle metropolitan region." You can participate in Marzluff’s crow research by entering your crow sightings on his Seattle crow observations website. Says Marzluff: "Urbanization is a pressing environmental issue worldwide. When folks ask me what they can do to enhance biodiversity, one thing I always point out is to look in their own back yards. People typically like fancier-looking shrubs and they like things to be very neat. Birds like native shrubs and messy things. So be messy! Don’t cut all the grass. Let some of it grow up and fall over so a junco can nest under it. Keep native ferns—salmonberry especially is an important species providing food and nesting substrate for native birds."

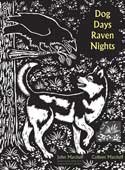

Recent books co-authored by Marzluff include In the Company of Crows and Ravens (with Tony Angell, 2005 Yale University Press), which suggests that human and crow cultures have co-evolved; and Dog Days, Raven Nights (with Colleen Marzluff, 2011, Yale University Press), chronicling the authors’ pathbreaking research on ravens in Maine’s north woods, where they also raised, trained and used sled dogs in their research. Marzluff and Angell’s second book, The Gift of the Crow, which will examine whether crows actually express emotions, is due out next year. * Photo by Keith Brust, courtesy of PBS April 2011 | Return to issue home | ||||||

|

||||||