August 3, 2006

Arctic magic draws writer in: Thomas weaves tale of shamanism

Lesley Thomas went to live in the Arctic at the age of 11 fresh from a tour of Europe with her grandmother. Dropped off in early winter by a bush plane, she rode into the village where her immediate family had settled on a dogsled pulled by a snow machine, with half the town’s population of 200 gawking at her.

“Here,” her mother said when she arrived. “Put on this parka and these mukluks and go out and play.”

Thomas obeyed, whereupon she was pelted with ice balls by the village boys, who must have thought she’d be an easy mark.

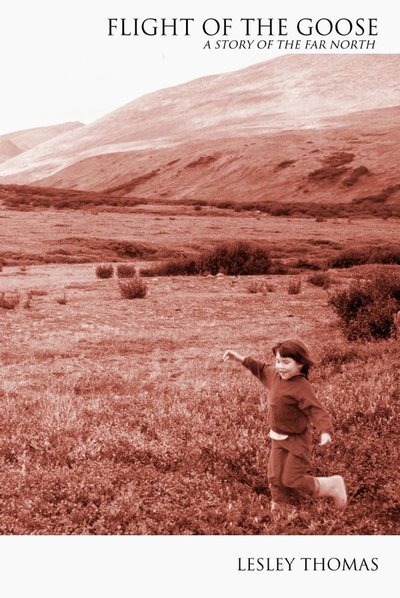

With such a shaky beginning, one might think Thomas would grow up hating the Arctic, but the opposite is true. Her love for the region oozes from the pages of her first published novel, Flight of the Goose, which is set in a village based on the one where she lived and others in the Bering Strait region.

“I have close ties to the Arctic. I return frequently,” Thomas says.

Contrary to the vision most of us have of a barren expanse of snow and ice, Thomas says her youthful home is teeming with life. Steep and rolling hills climb up into mountains with lots of rock formations. There are valleys with rivers, lakes and ponds. When you look closely, she says, there are millions of little plants — many species crowded together, like the Amazon jungle, only on the size of a postage stamp. So the willow trees that could be hundreds of years old are only a few inches high. And the tundra and salt marshes are prime breeding ground for migratory birds from all over the world.

Thomas, who now teaches in the UW’s English as a Second Language Program, lived in the Alaskan village of Shishmaref and the Arctic town of Nome from that inauspicious beginning at age 11 until her departure for college. Her parents were schoolteachers and fishers, her stepfather a native Inupiat. And although Thomas says the plot of the book isn’t her life story, all the background details are authentic to its place and time (1971).

Flight of the Goose deals with a young Inupiat woman, an orphan who — against her Lutheran adoptive family’s wishes — wants to be a shaman. The tale becomes a love story when she meets a bird biologist who comes to the area to study an endangered goose and also to look at the effects of oil spills on the salt marshes. But along with the romance there is cultural conflict, as science clashes with mysticism, Lutheranism with shamanism and environmentalism with economics.

Thomas worked on a study very like that of her biologist character while she was an undergraduate at Western Washington University. And like the Inupiat character, she’s drawn to shamanism, and has been since she was quite young.

Shamans in the Arctic, she explains, did their work through soul flight — going into a trance state and visiting other realms to bring back lost souls. They also struggled with evil spirits that were affecting the community. But there was a dark side to their work, as some shamans abused the power they had accumulated.

“Sometimes I think the book’s two main characters are based on my own two opposing mentalities and the love story is a Jungian integration of my two sides — the scientist vs. the mystic,” Thomas says.

She says her main intention in writing Flight of the Goose was simply to tell a good story. But the book also traces a time period in which global warming is ravaging her home village. Shishmaref has been eroded by increasingly fierce storm surges. No longer protected by pack ice, which is retreating, the village is literally falling into the sea.

“The building I lived in with my family is pretty much gone now,” Thomas says. “The people will have to be evacuated from all the little villages that have been there for thousands of years.”

So if the novel opens some eyes about the real effects of global warming, that will be satisfying for her.

A number of scientists, native Alaskans and eminent anthropologists of the Arctic who know the ecosystem, the cultures and the shamanic tradition and also the modern situation have endorsed Flight of the Goose as authentic. And they aren’t the only ones who admire the novel. It took first place in fiction in the National Federation of Press Women, the Washington Press Association, and the Alaska Press Women 2006 Communication Contests. It was nominated for the 2006 Pacific Northwest Booksellers Book Award, and became a top finalist.

That many honors are unusual for a book that was essentially self published. Thomas says there was interest in her manuscript 10 years ago when her agent showed it to New York publishers. But back then, “Editors thought nobody had heard of shamanism, nobody was interested in the Arctic.”

The publishers also put pressure on her to change the ethnicity of the main character because, Thomas explains, since she is not herself an Alaskan native, the book couldn’t be classified as ethnic writing. And Editors worried that an authentic native village woman as protagonist would not appeal to mainstream America. Some wanted the character’s personality to be more feminine.

Rather than give in to the pressure, Thomas decided to publish the book herself. Temporarily laid off from teaching when the number of UW international students dipped after Sept. 11, she used the time to promote the book through readings at bookstores. Over time, she sold more than 1,000 copies, a threshold that commands respect in the publishing world. That, combined with the awards, has led New York publishers to reconsider the book.

Meanwhile, Thomas is at work on a second book, also set in the Arctic and dealing with shamanism. But in this case it’s the European Arctic in ancient times and the conflict is between Vikings and Lapplanders (also known as Saami).

“I just seem to be irresistibly drawn to the Arctic,” Thomas says. “The Arctic fills me with a very ancient feeling of connection with the Earth.”