March 8, 2007

Lessons from Rita: How hurricane intensity change happens

Hurricanes can gain or lose intensity with startling quickness, a phenomenon never more obvious than during the historic 2005 hurricane season that spawned the remarkably destructive Katrina and Rita.

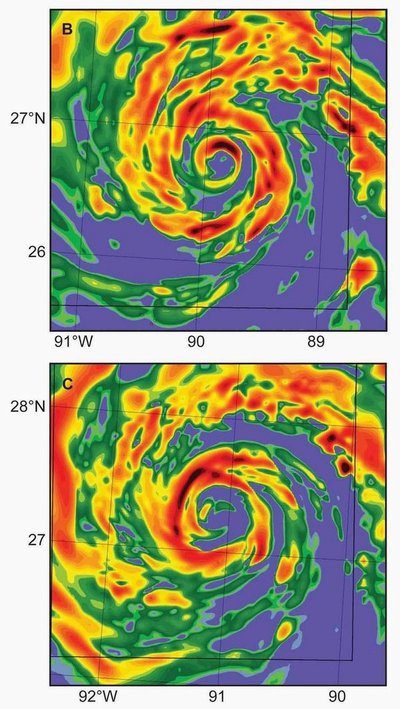

Researchers flew through Rita, Katrina and other 2005 storms trying to unlock the key to intensity changes. Now, data from Rita is providing the first documented evidence that such intensity changes can be caused by clouds outside the wall of a hurricane’s eye coming together to form a new eyewall.

“The comparison between Katrina and Rita will be interesting because we got excellent data from both storms. Rita was the one that showed the eyewall replacement,” said Robert Houze Jr., a UW atmospheric sciences professor and lead author of a paper detailing the work in the March 2 edition of the journal Science.

“The implication of our findings is that some new approaches to hurricane forecasting might be possible,” he said.

Houze and Shuyi Chen, an associate professor of meteorology and physical oceanography at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, lead a scientific collaboration called the Hurricane Rainband and Intensity Change Experiment. The project is designed to reveal how the outer rainbands interact with a hurricane’s eye to influence the storm’s intensity. Chen is a co-author of the Science paper, as are Bradley Smull of the UW and Wen-Chau Lee and Michael Bell of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo.

The project is the first to use three Doppler radar-equipped aircraft flying simultaneously in and near hurricane rainbands. The project also uses a unique computer model developed by Chen’s group at the Rosenstiel School.

“The model provided an exceptionally accurate forecast of eyewall replacement, which was key to guiding the aircraft to collect the radar data,” Chen said.

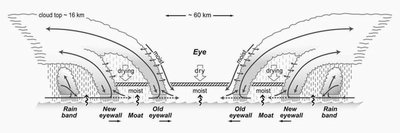

A hurricane’s strongest winds occur in the wall of clouds surrounding the calm eye. The researchers found that as the storm swirled into a tighter spin, a band of dry air developed around the eyewall, like a moat around a castle. But while a moat protects a castle, the hurricane’s moat eventually will destroy the existing eyewall, Houze said. Meanwhile, outer rainbands form a new eyewall and the moat merges with the original eye and the storm widens, so the spin is reduced and winds around the eye are slowed temporarily, something like what happens as a figure skater’s arms are extended. But the storm soon intensifies again as the new eyewall takes shape.

“The exciting thing about the data from Rita is that they show that the moat is a very dynamic region that cuts off the old eye and establishes a wider eye,” Houze said. “It’s not just a passive region that’s caught in between two eyewalls.”

Hurricane forecasters in recent years have developed remarkable accuracy in figuring out hours, even days, ahead of time what path a storm is most likely to follow. But they have been unable to say with much certainty how strong the storm will be when it hits land. This work could provide the tools they need to understand when a storm is going to change intensity and how strong it will become.

Scientists already knew that intensity can change greatly in a short time — in the case of Rita the storm grew from a category 1, the least powerful hurricane, to a category 5, the most powerful, in less than a day. Aircraft observation of the moat allowed scientists to see Rita’s rapid loss of intensity during eyewall replacement, which was followed by rapid intensification.

“Future aircraft observations focused in the same way should make it possible to identify other small-scale areas in a storm where the processes that affect intensity are going on, then that data can be fed into high-resolution models to forecast storm intensity changes,” Houze said.

That understanding could prove valuable for coastal residents deciding whether a storm is powerful enough to warrant their seeking safety farther inland. Rita and Katrina, among the six most intense Atlantic hurricanes ever recorded in terms of the barometric pressure within the core of the storm, struck just three weeks apart in August and September 2005, together resulting in some 2,000 fatalities and more than $90 billion in damage along the Gulf of Mexico coastline. The most intense Atlantic storm ever recorded, Wilma, also struck in the record-setting 2005 hurricane season, which produced 15 hurricanes, including a fourth category 5 storm, Emily, and a category 4 storm, Dennis.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration provided two research aircraft for the project and the third was provided by the U.S. Navy and funded by the National Science Foundation, which provided most of the funding for the project.

The planes flew several novel flight paths, including a circular track in Rita’s moat, to gather information from the edges of rainbands and other structures in the hurricane.

“We used a ground-control system with a lot of data at our fingertips to focus the aircraft into places in the storm where there were processes happening related to intensity changes,” Houze said.