March 29, 2007

‘Smart’ sunglasses and goggles let users adjust shade and color

Imagine a single pair of glasses with lenses that can be transparent or dark, and in shades of yellow, green or purple, all on command. A new lens with chameleon powers promises to dramatically improve sunglasses’ function.

Shades that can be controlled at the touch of a button would interest athletes, construction workers and anyone with sensitive eyes. The glasses are made possible by a new material uniquely suited to the task: a low-cost sheet that changes color and shade using almost no power. Prototype “smart” glasses were presented Tuesday in Chicago at the American Chemical Society’s 233rd national meeting.

“These lenses are more active, more intelligent, than today’s sunglasses,” said inventor Chunye Xu, UW research assistant professor of mechanical engineering. “But because of the materials we’re using we don’t think the price is going to be very different.”

Motorcyclists, skiers or mountain bikers might be in the shade one moment and pop into bright sunlight an instant later. Some high-end sunglasses already let athletes adjust to such changing conditions by swapping out lenses. But the new shades, which take from one to two seconds to transition, allow a much quicker switch. Current lens choices don’t simply include different levels of shading, but also different colors, such as yellow lenses, said to enhance contrasts and improve depth perception, or rose-colored glasses, which brighten low-light scenes. The new glasses would offer an wide range of options on one accessory.

Doctors already are recommending sunglasses that darken in response to the lighting conditions, known as photochromic lenses. These use incoming UV rays to trigger a chemical reaction that darkens the lens, but users can’t adjust the shade. Also, the lenses may stay bright under strong midday light or get too dark in low-level evening light due to the angle of incoming rays. And photochromic lenses have the drawback that when behind a UV-protected surface, such as a car window, the glasses won’t change color. Adjustable lenses would avoid this problem.

Researchers made the glasses using electrochromic materials that change transparency depending on the electric current. Many groups, including the UW, are developing such materials for so-called “smart windows” that could soon be used in energy-efficient homes and offices. Most smart windows use liquid-crystal technology or inorganic oxides. Those materials are expensive to produce and require a constant or frequent injection of power to hold their tint. The UW glasses are based on a new type of smart window using organic, rather than inorganic, oxides. These are cheaper to manufacture and require less power.

The prototype glasses are powered by a watch battery that attaches to the glasses frame, and the wearer spins a tiny dial on the arm of the glasses to change color or shade. The lenses were created by sandwiching a gel between two layers of electrochromic material. Applying a small voltage moves charged particles from one layer to another, and changes the transparency. Once the glasses are a certain tint they will stay that way without power for about 30 days. A single watch battery is able to power thousands of transitions, Xu said.

Organic molecules allowed the researchers to create colored lenses.

“In organic materials, the elements are simple but the structure is much more complicated,” Xu said. “We can add more branches to this structure and tune in colors.”

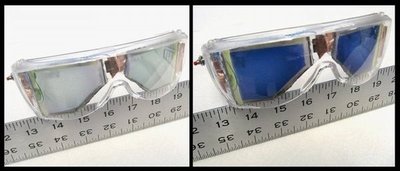

The prototype glasses change from dark blue to light blue. Xu and her colleagues have developed other adjustable lenses in red and yellow. In the future, they will layer sheets to create a range of colors in a single pair of shades.

“These are a little homemade,” Xu said of the prototype, a modified pair of lab goggles. She plans to incorporate the lenses in more fashionable frames. Xu’s group has a number of patents filed on the technology and is exploring options for commercialization. It will be a few years until these sunglasses show up on store shelves.

This research was funded by the UW’s Technology Gap Innovation Fund. Collaborators on the project are Minoru Taya, professor of mechanical engineering and director of the UW Center for Intelligent Materials and Systems, and doctoral student Chao Ma.