April 29, 2010

Jose Alaniz pens history of Russian comics — ‘from the icon to the internet’

There are no comic book shops in Russia, says Jose Alaniz, assistant professor of Slavic Languages and Literature — no deep appreciation of heroic or sensational comic adventures by the mainstream. In fact, he says, there really is no mainstream.

Still, there have been comics in various forms in Russia for more than a century, “burning in the summers of relative freedom, freezing in the hard winters of official disdain,” Alaniz writes.

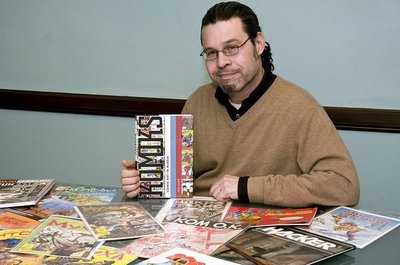

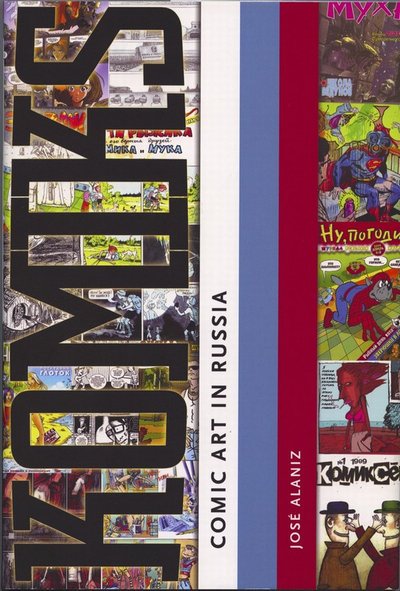

Alaniz has just released the first written history of this struggling Russian art form. Komiks: Comic Art in Russia was published in March by the University Press of Mississippi. He said his intent with the book was to shed light on comics in “a place where most people assumed they could not exist or would not exist because of communist antipathy toward the form.”

No one else was doing similar work, he said, “and most Russians themselves just don’t have any real affection for this form, for all sorts of historical reasons.”

Alaniz’s background seems to make him uniquely qualified for the job. “I grew up reading comics … in fact it was the way I learned to read, earlier than many of my peers. And it was also the way I learned drawing and the interaction of word and image.”

He brought that interest to Moscow when he worked there as a journalist in 1993 and 1994, and a fondness for Russian comics also began to bloom. He was fortunate to meet Georgy ‘Zhora’ Litichevsky, a Moscow artist who had long incorporated comics into his practice. “His work really inspired me to dig deeper into the scene in what was then a rather dark, pre-Internet period for comics in Russia,” Alaniz said. That association led to others and by 2004 the project was under way even as he finished up his dissertation at the University of California, Berkeley.

“So, it was a long, stop-and-start process, which took about 15 years from initial interest to this year’s book publication.”

First came definitions: What counts as a comic? “For me … the critical essence of comics has to do with pictures in sequence, usually to tell a narrative, to have some kind of sequential art aspect to them.” That excluded paintings, even those telling stories, because they were not sequential.

Looking for “a comics language …a sensibility,” he studied icons from the pre-revolutionary era as well as satirical journals, wood block prints called Lubok and even small, fold-out pamphlets depicting Bible scenes that clergy used as teaching tools. Russian comics, he said, entered their modern phase in 1895, about the same time as the dawn of the movies.

While comics were loved in the West, he said, they were often vilified in Russia for being “bourgeois art and pseudo-literature.” Touches like sound effects and word balloons were disparaged as too crassly American. “In fact, you might have word balloons appear but they appear to characters that are identified as American — usually as spies, or as American generals.”

The Perestroika era, with its mild warming trend toward the West, brought the beginnings of a fledgling Russian comics industry. “It happens in 1988, with the founding of KOM, the first comics studio in the Soviet Union devoted specifically and exclusively to making comics,” Alaniz said. But these were humble efforts. “Compare them to a modern comic — they are ultra cheap and they are made on cheap paper, not very good printing, black and white.” KOM folded up in 1993, unable to compete in the growing free market.

Though comics were by then slowly spreading in Russia, readers were still cool to the form. “Make no mistake,” Alaniz said, “even after they started publishing this stuff in a newspaper, Evening Moscow … they got lots and lots of hate mail” and many readers even dropped their subscriptions.

Not surprisingly, the coming of the Internet caused an explosion of Russian comics, which Alaniz dates to 1999, when Komiksolet, the first website and clearinghouse for comics, was launched. The first Russian comics festival, KomMissia, was held in Moscow in 2002. “It’s great for the art form but does nothing for the business,” he said.

Sadly, reader attitudes toward the comics don’t warm much, despite the increased availability. “That’s part of the fundamental point of the book,” Alaniz said. “When we get to the post-Soviet era, we discover that these prejudices against comics were not Soviet, they were actually Russian, they were shared by the Russian people. Because a lot of things changed after 1991 and the collapse of the Soviet Union, but that doesn’t change — people continue to hate comics.”

The Internet did little to nurture a Russian comics industry. Alaniz writes in the book, “With so much free content on the Internet, print publishers proved even more reluctant to finance large-scale projects or series, and continued to cede much of the domestic market to foreign translations of Marvel and Disney.”

And why not? “It’s much more difficult to come up with your own ideas and your own characters, pay your artists, lay it all out, write it all and then publish it. … It’s not going to look good, and you’re going to go out of business, and that’s exactly what happened with dozens of publishers in the 1990s. It’s much cheaper to pay a pittance for foreign publication rights to Spiderman, a well-known global brand that’s already drawn and laid out in an attractive package. Then just sit back and count your money.”

Alaniz divided his book into two parts. The first four chapters discuss the history of comics in Russia from their roots in religious practices to their “Soviet-era semi-exile to the margins of culture, to the promise and catastrophes of the postsocialist era of predatory capitalism.”

Then the book moves to “its proper focus,” Alaniz writes: “close readings of individual work and/or artists, from a cultural studies perspective.” He adds, “My goal … is to acquaint the reader with the enormous scope, diversity and peculiarity of Russian comic art, especially of the contemporary period, at the same time providing a sense of the cultural conditions that led to its long troubled history and continue to affect its development in the twenty-first century.”

The future of Russian comics seems to forever remain in doubt. “It’s a tragic story,” Alaniz said. “On the one hand it’s flourishing with comics online — there’s a wonderful audience and wonderful people doing amazing work. (But) most of their work appears online and they make no money off it. It’s kind of a hobby.”

An illustrated children’s journal called Just You Wait shows Alaniz a glimmer of hope, however. Cleverly named for a popular animated program from the 1960s and 1970s — “it’s like calling your journal Tom and Jerry or something,” he said — the program began in 2004 and uses the familiarity of the old program as a way of slowly introducing new characters and creating a brand.” “It’s very smart, and it’s the only way to compete with those foreign brands.”

Alaniz said, “It’s going to be ventures like that, to create an actual mainstream, and actual comics for kids — I mean real Russian comics for kids to get them interested at a young age.” He added, “That’s what happened to me. They got me at a young age.”

Komiks represents a major step in Alaniz’s career, and he said it was helpful in his achieving tenure at the UW. He’s pleased to have had a few inquiries about translating it into Russian, and said he may also start a blog about Russian comics.

“I just hope other scholars and general readers will find my book interesting and helpful,” he said. “My book is the first — by no means last! — word on Russian comics culture.”