October 28, 2010

A life to be remembered: ‘Dr. Sam’ tells story of UW’s Samuel E. Kelly

Samuel E. Kelly led an extraordinary life. He served the U.S. Army with distinction through two wars and joined the UW at a turbulent time to create and run its Office of Minority Affairs. Kelly had a commanding presence and promoted equality and minority studies with powerful strength of conviction.

All of which made it a pleasant challenge for History Professor Quintard Taylor — who says he acted as a sort of “modern-day scribe” — to get Kelly’s life story told on paper in the man’s own voice. “I wrote every word, but I wrote his words,” Taylor said. “I’m conveying his words and ideas.”

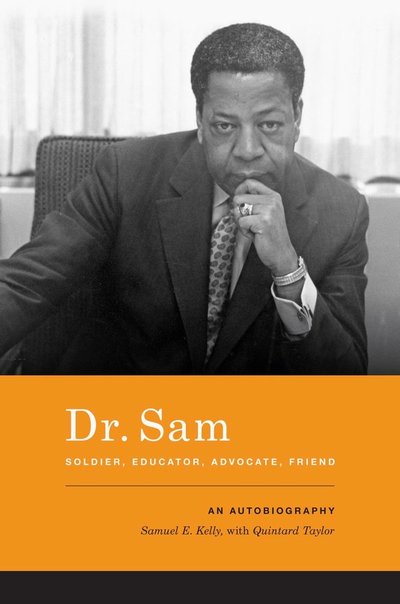

That story, titled Dr. Sam: Soldier, Educator, Advocate, Friend — Kelly’s assisted autobiography — was published this month by University of Washington Press. Warmly and smoothly told, it follows Kelly from his birth “to a poor family in one of the wealthiest towns in the nation,” Greenwich, Conn., through service in World War II and Korea — where he was among the first black officers to command both black and white troops in combat — through his years building respected minority studies programs at Shoreline Community College and the UW.

Along the way, Kelly was inspired by the people he met — especially Paul Robeson, the great African American actor whom a teenage Kelly took a date to see play Othello in 1943. “(H)e came out and greeted each of us, shaking our hands with his gigantic hand, very affectionately. Before we could sit down, he bellowed in his deep voice, ‘Now, what are you going to do for the race?'”

Taylor said, “That as much informed who he was, what he did and what he was about at 86 as when he first heard it — and he was just as committed to that idea the day he died,” Taylor said. “It was very important for him. That’s what animated his entire life.”

Kelly also questioned authority throughout life — even when he became part of that authority.

Kelly served in the army in post-World War II Japan, and his selfless leadership under fire in Korea earned him medals for bravery. “The greatest accolade, however, came from my men,” Kelly remembered. “My platoon gave me the nickname ‘Combat Kelly.'”

Retiring from the army at 40 in 1966, Kelly summed up that career with pride: “During my 22 years of active service, I rose from the rank of private to lieutenant colonel, served as part of the occupying army in Japan, saw combat in Korea, joined and led an elite airborne unit, and crafted plans and operations for upward of 50,000 soldiers.” He added, “This was not a bad career for a Connecticut kid who had dropped out of high school.”

By then, Kelly had BA and BS degrees from West Virginia State College and an MA from Marhsall University. He taught awhile at what was then Everett Junior College, and in time took a position at Shoreline Community College, teaching African American history and acting as special assistant to President Richard White.

There he helped create Shoreline’s first Minority Affairs Program. The four components of that program would later be the model for similar work at the UW: academic courses, academic and social counseling, financial aid to minority students and recruitment of faculty and students of color.

Even while working at Shoreline, Kelly was pursuing a doctorate with the UW College of Education, and this was awarded in December of 1971, making him truly Dr. Sam.

Kelly was hired at the UW in the spring of 1970, to officially start that fall. “At that point,” he wrote, “the administrators who ran the (UW), a campus of 33,000 students and a faculty and staff of 12,000, were all white males.”

But his role was challenged before he even started work. Protests over the Vietnam War and civil rights were simmering nationwide, and grew worse that spring with America’s invasion of Cambodia. The UW closed for a day in April to honor four Kent State University students shot dead by National Guard troops. In May when two black students were killed at Jackson State University, angry black students demanded the UW close to honor those lives as well. Odegaard called Kelly in to investigate — and Kelly agreed with the students, and told Odegaard so. The UW closed its doors a second time on Monday, May 18, 1970.

It was Kelly’s talent at bringing together different sides of an issue that won the day, Taylor said. “He was the kind of person who could at least understand the militants, and he could sympathize with them and could teach them in his class … And in fact, he saw these ideas in context with the longer civil rights struggle that he had been engaged in most of his life.”

Kelly felt he was taking Paul Robeson’s advice even as he was building up the Office of Minority Affairs at the UW. Asking for substantial funding, he told Odegaard, “We are, through this program, in a small way attempting to atone for centuries of slavery and racial discrimination, for Western imperialism. We are making a modest down payment on a debt we owe to millions of people.” He also insisted, surprising some, that benefits be extended not only to students of color, but also to low-income white students.

Kelly went on to serve in later years as special assistant to the UW president and director of the UW’s Black Studies Program, before leaving the UW in 1980 and going on to several other positions in the 1980s and 1990s before his retirement.

Taylor said the book came from “hours and hours” of taped interviews with Kelly, who had a “fascinating attention to detail … 97 percent of the time, he was uncannily accurate in terms of the various events he would recall.”

Kelly died just weeks after the two finished the manuscript in 2009, and was content with the book, Taylor said. “He was in great spirits after we turned in the manuscript and he was proud of the job that we had done together.” Taylor also said Kelly was delighted to live to see the first African American in the White House.

Taylor added, “This is a guy who grew up in a time when most black folks couldn’t vote … and he remembered his parents’ stories from all the people who came up from the south, and that was very important to him. I tried to express that in the book — I mean, his whole life has been a battle against discrimination.

“Even though he is no longer with us, I remain in awe of Sam Kelly,” Taylor said.