I taught the first online learning course at the University of Washington in 1995. My co‑instructor was Dr. Norm Coombs, at the time a professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology. We designed the course to be accessible to anyone, including students who were blind, were deaf, had physical disabilities, or had multiple learning preferences. Norm himself is blind. He uses a screen reader and speech synthesizer to read text presented on the screen. We employed the latest technology of the time—email, discussion list, Gopher, file transfer protocol, and telnet (no World Wide Web yet!). All online materials were in a text-based format, and videos, presented in VHS format with captions and audio description, were mailed to the students. When asked if any of our students had disabilities, we were proud to say that we did not know. Why? Because no one needed to disclose a disability since all of the course materials and teaching methods were accessibly designed.

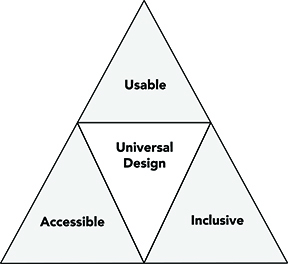

Technology has changed dramatically since I first taught online, but the basic principles that can guide the design of accessible courses have not. The term UD was coined by Ronald Mace, an architect, product designer, and wheelchair user whose work led to the creation of the Center for Universal Design (CUD) at North Carolina State University and its seven principles of UD. UD is defined as "the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design." The UD definition, principles, and guidelines were created to make any application accessible, usable, and inclusive and, thus, are a logical choice to underpin practices that ensure that online courses meet the needs of potential students with a wide variety of characteristics that include those related to gender identity, race, ethnicity, culture, marital status, age, abilities, interests, values, learning preferences, socioeconomic status, and religious beliefs.

For a history of UD, the basic principles of UD and those that later evolved to address issues specific to the design of learning activities and IT, consult my book Creating Inclusive Learning Environments in Higher Education: A Universal Design Toolkit and other resources presented in the Center for Universal Design in Education, which is hosted by DO-IT Center at the University of Washington—where DO-IT stands for Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology. For resources specific to applications of UD to online learning, including accessibility checkers, legal issues, technical details, and promising practices, consult AccessDL.

A statement about how students can request disability-related accommodations should be included in the syllabus. Then instructors can apply the 20 tips I list below, as they begin to work toward making their online courses more inclusive. The complementary video, 20 Tips for Instructors about Making Online Learning Courses Accessible, may be viewed online, along with a tutorial for further background and directions for implementing these tips.

Tips

Nine tips for course materials follow. Consult Accessible Technology at uw.edu/accessibility for details on the design, selection, and use of accessible IT as well as accessibility checkers that help you identify accessibility problems in materials you use or create:

- Use clear, consistent layouts, navigation, and organization schemes to present content. Keep paragraphs short and avoid flashing content.

- Use descriptive wording for hyperlink text (e.g., “DO-IT website” rather than “click here”).

- Use a text-based format and structure headings, lists, and tables using style and formatting features within your Learning Management System (LMS) and content creation software, such as Microsoft Word, and PowerPoint and Adobe InDesign and Acrobat; use built-in page layouts where applicable.

- Avoid creating PDF documents. Post most instructor-created content within LMS content pages (i.e., in HTML) and, if a PDF is desired, link to it only as a secondary source of the information.

- Provide concise text descriptions of content presented within images (text descriptions web resource).

- Use large, bold, sans serif fonts on uncluttered pages with plain backgrounds.

- Use color combinations that are high contrast and can be distinguished by those who are colorblind (color contrast web resource). Do not use color alone to convey meaning.

- Caption videos and transcribe audio content.

- Don’t overburden students with learning to operate a large number of technology products unless they are related to the topic of the course; use asynchronous tools; make sure IT used requires the use of the keyboard alone and otherwise employs accessible design practices.

Eleven tips for inclusive pedagogy follow; many are particularly beneficial for students who are neurodiverse (e.g., those on the autism spectrum or who have learning disabilities). Consult Equal Access: Universal Design of Instruction for more guidance.

- Recommend videos and written materials to students where they can gain technical skills needed for course participation.

- Provide multiple ways for students to learn (e.g., use a combination of text, video, audio, and/or image; speak aloud all content presented on slides in synchronous presentations and then record them for later viewing).

- Provide multiple ways to communicate and collaborate that are accessible to individuals with a variety of disabilities.

- Provide multiple ways for students to demonstrate what they have learned (e.g., different types of test items, portfolios, presentations, single-topic discussions).

- Address a wide range of language skills as you write content (e.g., use plain English, spell out acronyms, define terms, avoid or define jargon).

- Make instructions and expectations clear for activities, projects, discussions and readings.

- Make examples and assignments relevant to learners with a wide variety of interests and backgrounds.

- Offer outlines and other scaffolding tools and share tips that might help students learn.

- Provide adequate opportunities to practice.

- Allow adequate time for activities, projects, and tests (e.g., give details of all project assignments at the beginning of the course).

- Provide feedback on project parts and offer corrective opportunities.

These tips apply to both synchronous and asynchronous teaching. Additional tips for synchronous presentations (e.g., speak all content presented visually, turn on the caption feature of your conferencing software, do not require students to have their cameras on) can be found in Equal Access: Universal Design of Your Presentation.

Acknowledgments

DO-IT (Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology) serves to increase the success of individuals with disabilities. This publication was partially funded through DO-IT’s AccessCyberlearning project that is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF Grant #1550477). Any questions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF. More information about DO-IT can be found at uw.edu/doit.

Copyright © 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2015, University of Washington. Permission is granted to copy these materials for educational, noncommercial purposes provided the source is acknowledged.