Chapter Two

Steps to Creating an E-mentoring Community

We make a living by what we get. We make a life by what we give.

— Sir Winston Churchill —

Creating an online mentoring community requires access to technology and Internet communication tools, administrative infrastructure, and ongoing facilitation. Following are steps for setting up your own e-mentoring community for teens with examples from the successful practices employed by DO-IT. Sample forms and documents that can be modified to suit your program are provided in Chapter Thirteen.

View the video Opening Doors: Mentoring on the Internet, for an overview of DO-IT's electronic mentoring community, as well as for testimonials from participants. To understand the program context of this e-mentoring community, view the video How DO-IT Does It. These video presentations can be purchased from DO-IT in DVD format or freely viewed on the DO-IT Video page. Consider what goals, characteristics, and outcomes of DO-IT's e-mentoring community you hope to tailor to your program.

Acknowledgement: A summary of these steps is published as an Information Brief by the National Center Secondary Education and Transition (Burgstahler, 2006b).

Establish clear goals for the program.

The ultimate goal for DO-IT participants is a successful transition to adult life. In DO-IT's supported community, participants prepare for college and employment, develop social competence, learn to use the Internet as a resource, reflect on their own experiences, practice self-determination and leadership skills, and learn from others.

Decide what technology to use.

Email coupled with electronic distribution lists, message boards, web-based forums, and chat rooms are all possibilities for supporting peer and mentor interactions. Chat and other synchronous methods require that participants be on the same schedule; this condition is too restricting for most programs. In addition, these systems are not accessible to all students, in particular to those who are very slow typists. Web-based forums are a possibility, but they require that students and mentors regularly enter the message system to participate, thus all participants must have both the motivation and the discipline to regularly access the system, and this is not true of all teens.

DO-IT has been successful with using electronic mail and distribution lists to maintain its electronic mentoring community. This text-based asynchronous approach is fully accessible to everyone and results in messages appearing in participant email inboxes. As long as they regularly access their email, it is difficult for students and mentors to ignore the conversations that occur. Guidance to participants regarding how to manage email correspondence (e.g., using folders, deleting old messages) is provided as part of participant training.

If you are interested in setting up a distribution list ask your Internet service provider if it has the capability to do this. Also explore web-based options such as those provided by topica and yahoo. All of these options forward to all members of a list any email messages sent to the list address. Assign the participants to distribution list(s) that are closed; in other words, individuals cannot become part of the community without going through the application process managed by the administrator.

Select only universally-designed technology to use for communication in your community. This means that it is fully accessible to all potential participants, including those who have disabilities. Make sure that a person who is deaf or who has a speech impairment can participate in all communications. Technology you choose should also be fully accessible to individuals who are blind and using text-to-speech adaptive technology as part of their computer system. Consult DO-IT's website on Accessible Technology for more information about accessible technology.

Establish a Discussion Group Structure.

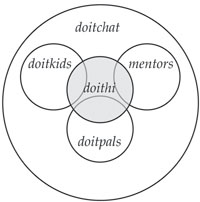

When DO-IT had only a small number of participants, there were two e-mentoring community discussion lists, doitkids@u.washington.edu for the DO-IT Scholars and mentors@u.washington.edu for the Mentors. Mentors could communicate with each other on the mentors list, and teens could communicate with each other on the doitkids list. Messages were sent to both addresses simultaneously for conversations that included all Mentors and Scholars, like those labeled E-Community Activity in the remaining chapters of this book. When the DO-IT Pals program emerged, we created a list for these participants, doitpals@u.washington.edu. To better facilitate large-group discussions we eventually set up a distribution list, doitchat@u.washington.edu, that includes all of the members of doitkids@u.washington.edu, mentors@u.washington.edu, and doitpals@u.washington.edu. Discussions that include the full e-community take place on the doitchat list.

As the DO-IT community grew in size, individuals expressed an interest in continuing with large group conversations but also communicating in smaller groups with people whose accommodation strategies are similar to their own. To address this need, we set up several more discussion lists. For example, doithi@u.washington.edu was set up for mentors, near-peers, and protégés who have hearing impairments. Members of this list discuss topics that might not interest the larger community, such as sign language interpreters, FM systems, and cochlear implants. The figure above illustrates how individuals in the doithi group are drawn from members of the other groups.

Similarly, special distribution lists were set up for individuals with visual impairments, learning issues, and other classifications. A lead mentor and at least one DO-IT staff member is included on each distribution list to facilitate communication and to assure that all messages are appropriate.

Example of the DO-IT Discussion List Structure for Participants with Hearing Impairments.

Each doithi member is also a member of doitchat and one of the groups doitkids, doitpals, and mentors.

Select an administrator for the e-mentoring community, and make other staff and volunteer assignments as needed.

The DO-IT electronic community promotes communication in group discussions that involve many mentors, near-peers, and protégés. However, to maximize participation in large communities, it is important to assign each protégé to a specific mentor who will assure the participant's regular involvement and satisfaction, but not limit his/her communication with others. For greater assurance of follow-through, it is desirable for these mentors to be paid staff. In DO-IT, for example, all DO-IT Scholars and Ambassadors are assigned to key staff members who communicate with them personally on a regular basis.

To assure supervision of lead mentors and coordination with other staff, an e-community manager was assigned. This role also includes obtaining the informed consent of parents as well as the collection and dissemination, to appropriate groups, of web resources and other information of specific interest. Other staff assignments include technical support (e.g., subscribing individuals to the distribution list and correcting email address errors) and mentoring leads for subgroups of the mentoring community.

Develop guidelines for protégés concerning appropriate and safe Internet communications.

Relationships developed with mentors become channels for the passage of information, advice, opportunities, challenges, and support, with the ultimate goals of facilitating achievement and having fun. Keep in mind that, although the majority of Internet resources and communications are not harmful to children, participants may stumble into situations or be encouraged to participate in communications that are inappropriate. They may encounter objectionable material by innocently searching for information with a search engine or mistyping a web address. On the Internet, they might:

- see materials that include content that is sexual, violent, hateful, or otherwise inappropriate for children

- be exposed to communications that are harassing or demeaning and, perhaps, even be drawn into these types of conversations themselves

- be encouraged to participate in activities that promote prejudice, are unsafe, or are illegal

- meet a predator who uses the Internet to develop trusting relationships with kids and then arranges to meet them in person

- make unauthorized purchases using a credit card

Teenagers are particularly vulnerable to being exposed to material and engaging in activities that are inappropriate. This is because they are more likely than younger children to use computers unsupervised; have the skills to conduct searches on the Internet; participate in online discussions via email, chat, instant messaging, or bulletin board systems where inappropriate communications can occur; and have access to credit card information.

If your electronic community includes young people under the age of eighteen, obtain the informed consent of parents or guardians, making the risks and benefits of using the Internet clear. Sample content for a permission form for parents or guardians to sign is included in Chapter Thirteen of this book. Seek advice from legal experts in your organization or community as you explore ways to keep participants safe.

Establish rules for participation in your community, and distribute them to the participants and mentors. Appropriate rules depend upon the ages of participants and the nature of the community. Consider adopting a set of expectations similar to Kids' Rules for Online Safety, published at SafeKids.com. Tailor them for your participants and encourage families to post them near Internet-connected computers in their homes. The guidelines should include your expectations for participation in the community (for example, check messages each week), child safety issues, and a statement that tells young participants to inform their parents and the e-community administrator if they receive email that is inappropriate or makes them uncomfortable. Sample guidelines can be found in Chapter Thirteen of this book.

Establish roles and develop guidelines, orientation, and training for mentors.

Determine what roles you desire mentors to perform in the program. Then develop guidelines for mentors, as well as program goals and operations that are consistent with these roles. The guidelines should be simple and straightforward and shared with potential applicants so that they understand mentor responsibilities.

Decide in what form(s) orientation and training should occur. The optimal amount of training depends on the complexity of your program and the expected roles of mentors. It is best if the training is interactive and engaging. Topics covered in the orientation should include

- an overview of how communication is to occur. In the case of DO-IT, an email message is sent to a specific discussion list or to an individual.

- an outline of the responsibilities, expectations, and boundaries your program has developed for both mentors and protégés.

- general mentoring tips, as well as tips designed to teach mentors how to promote success, self-determination, and problem solving skills.

- information to improve skills such as effective communication strategies and email netiquette.

- resources for mentors, such as additional mentor training, disability information, education, and career development.

See Chapter Three for more information on mentor orientation and training.

Standardize Procedures for Recruiting and Screening Mentor Applicants.

Consider what recruiting methods and screening devices will be used to choose mentors. Written applications, personal interviews, reference checks, and criminal record checks should be considered. Make sure that the application packet addresses the orientation, motivation, and skills needed to perform mentoring roles and includes established mentoring guidelines. Assign one staff member to review the application packet and to call references. Consider having a panel make final decisions on selections.

In DO-IT, mentoring opportunities are communicated by word of mouth through organizations with which DO-IT has connections. This approach helps assure the quality of mentors and the safety of participants. We provide prospective mentors with an application form that includes questions similar to those in the Sample Mentor Application in Chapter Thirteen of this book. For further suggestions on recruiting mentors, consult Recruiting Mentors: A Guide to Finding Volunteers to Work with Youth at www.ppv.org/ppv/publications/assets/28_publication.pdf.

Determine how to recruit protégés.

Decide how best to recruit participants to your program. In DO-IT, information about the DO-IT Scholars and DO-IT Pals programs is regularly distributed to schools, parent groups, and organizations that come in contact with teens who have disabilities. Teenagers submit application materials to join the competitive DO-IT Scholars program. An advisory board selects Scholars by reviewing their applications, teacher recommendations, parent recommendations, and school records. In the DO-IT Pals program, potential participants submit a short online application to doit@u.washington.edu; if they meet the basic criteria, they are included in the electronic community as DO-IT Pals. When individuals are accepted into the DO-IT Scholars and DO-IT Pals programs, their email addresses are added to appropriate distribution lists according to their program memberships and disabilities.

Provide Guidance to Parents.

Help parents understand both the benefits and risks of Internet access for their children. Encourage parents of participants to put their Internet-connected computers in high-traffic areas of their homes. If an Internet-connected computer is in the family room or other busy area, children will be less likely to engage in inappropriate activities. They should avoid having a computer with an Internet connection in a child's bedroom; this might be a better place for a computer with educational software, applications software, and games that do not require the Internet.

Encourage parents and guardians to talk to their children about both the benefits and the dangers of the Internet. They should describe scenarios in which a child could be exposed to inappropriate resources or communications. These conversations should be periodic and along the same lines as those about where it is safe for children to ride their bicycles and what to do if a friend wants to play with his dad's gun. They need to be clear about what activities their children are allowed to engage in, what types of Internet resources are and are not appropriate for them, and what they are to do if they encounter materials that they feel uncomfortable with or that they know are unacceptable to their parents. Children should also know what they should do if a friend exposes them to Internet use they know is wrong.

Parents and guardians should tell their children not to give out identifying information (for example, their last name, home address, phone number, or school name) in a chat room, on an email discussion list, or in a message to an individual that they and their children do not both know and trust. Children should never respond to messages that are harassing, threatening, of a sexual nature, or obscene or that make them feel uncomfortable in any way. Protégés should know that mentors may be valuable resources to them but that they need to take responsibility for participating only in conversations and activities that are appropriate and report concerns to parents and the e-mentoring community administrator.

Parents and guardians should be sure their children know to never arrange a face-to-face meeting with people they meet on the Internet, even if they are mentors or other program participants, without parental permission. If a parent approves of a meeting between his or her child and a person met on the Internet, they should accompany the child and arrange to meet in a public place.

Consider supporting an e-community for parents of participants. In DO-IT, we created a discussion list, doitparent@u.washington.edu to facilitate ongoing communication between DO-IT Scholar parents and DO-IT staff.

Establish a system whereby new mentors and protégés are introduced to community members.

The electronic community administrator can send messages to introduce new mentors or protégés to the group and invite new members to send messages about themselves to the group. For example, the administrator of the DO-IT online community might send the following message when a new DO-IT Mentor, Jane Smith, joins the program.

To: doitchat@u.washington.edu

Subject: Please welcome a new mentor

Hello everyone,

I would like all of you to please help me welcome Jane Smith to the DO-IT community. Jane is a new mentor who works for a local computer manufacturing plant. Please take a moment to send an email to Jane and introduce yourself. You can reach her directly at janesmith@mentor.com.

Welcome to the DO-IT community, Jane!

[name]

E-Mentoring Administrator

DO-IT also publishes DO-IT Snapshots and distributes it to all e-community members. This publication includes current bios and email addresses of participants. A version without email addresses can be found online on the DO-IT Snapshots page.

Provide Ongoing Supervision of and Support to Mentors.

Addressing the needs of mentors is key to a successful mentoring community. Most mentors experience some frustration and confusion regarding their roles, especially early on. Access to administrative staff and other mentors can help them get past the rough spots as well as provide ongoing guidance. The mentoring community administrator can model how discussion questions can be submitted to a group. When mentors send good questions to the list, the administrator can send an appreciative email to their individual email addresses.

Administrative staff should have regular communication with each mentor to address questions and identify challenges and solutions. These interactions help mentors feel appreciated, maintain a positive attitude, and maximize success in their mentoring roles. The mentoring community administrator should privately encourage individual mentors, near-peers, and protégés to participate when they have not done so in a while.

A discussion list or other electronic forum just for mentors can be used by mentors to support one another. In addition, the electronic community administrator can support the mentors by sending specific resources and guidance to this discussion list periodically, as is done with the messages labeled Mentor Tip in future chapters of this book. For additional ideas regarding the support of mentors, consult the publication Supporting Mentors at www.ppv.org/ppv/publications/assets/31_publication.pdf.

Monitor and manage online discussions.

In a perfect world you could create an electronic distribution list or a web-based forum for protégés and mentors with guidelines for their interactions, and they would automatically communicate with one another appropriately and regularly. This is the essence of how a topical listserv/listproc discussion list typically works. However, in a mentoring community you have more specific goals for the participants than simply to discuss a common interest. Someone needs to be assigned the tasks of monitoring and managing the discussions of the mentoring community and sending discussion questions when needed to promote interactions. There are no formal rules to employ, but the person with that assignment can benefit from using the content in future chapters of this book as a guide.

After providing general guidelines and training to new mentors, introducing them, and encouraging them to send messages introducing themselves, the mentoring community administrator can send one short, engaging message on one topic at a time and allow time for discussion before sending out a message on another topic. The administrator can then monitor conversations and assure a natural flow of communication. Some messages are best sent by a specific mentor or protégé. In this case, the administrator can ask a specific participant to send the message to the group. This approach assures that discussions are dominated by mentors and protégés, not program staff.

Protégés should be encouraged to send messages with a focused subject line and a question related to their current experiences. For example, the administrator could encourage a participant to submit the following question to the group: "I'm applying for a summer job and need to send a résumé and cover letter. I expect I will need disability-related accommodations to succeed in the position available. Should I inform the potential employer of my disability now, wait until I get invited for an interview, or wait until I am offered the job?"

Developing good questions to discuss is essential. This book gives you some great examples, but you will want to develop your own and have your participants do the same. Program staff should view their role as community facilitators, not the central focus. To support a discussion, administrators can do the following:

- Use questions that are short, focused, open-ended, and of interest to most participants and that solicit a variety of opinions rather than one right answer.

- Rephrase or provide an example related to a question if participants seem confused.

- Use subject lines that specify the focus of the discussion, for example, "Disclosing a disability in employment?"Avoid vague subject titles like "Question from a mentor."

- Submit comments to keep a conversation going, but back off when participants are keeping the discussion lively by themselves.

- In private email messages, encourage mentors and protégés to submit questions to the group.

- Promote communications from participants. For example, after someone's contribution you might send a message such as one of the following: "What a great story, John. What did you learn from this experience?" "Sherry, could you share with the group more about how you applied for this scholarship?" "Tell us about what accommodations you're using on your new job." "How did the reaction of that teacher make you feel?" "If you had this to do again, would you take the same action?"

- Whenever possible, let the participants resolve their own disputes, and reprimand privately those who send inappropriate messages. Rarely is it necessary to send such a message to the whole group.

Share resources

The e-mentoring community administrator or another staff member should search the Internet for useful resources and provide regular messages that point to these resources. There is no guarantee that individuals will make use of content in these electronic lessons, but participants are likely to make use of at least some of the content if it is tailored to the interests of the audience.

DO-IT staff search for and distribute to appropriate lists useful resources on college and career preparation, scholarships, internships, and other appropriate topics for the community. DO-IT has also developed a standard format for lessons to support its academic and career goals for young people in the program. One lesson is sent to the mentoring community each Friday with a standard subject line of "DO-IT Lesson: [lesson title]." For samples of these messages, consult DO-IT Internet Lessons. Permission is granted to distribute the lessons provided at this site to your participants provided the source is acknowledged. These lessons complement the interactive activities included in future chapters of this book.

Employ strategies that promote personal development.

Coordinating mentor-, near-peer-, and protégé-initiated discussions and sending out periodic lessons with useful resources are important activities for supporting an electronic community. Many other mentoring strategies can be modified for online delivery to support young people on their journeys toward successful, self-determined lives. The types of online activities for teens included in this book apply recognized strategies for self-development. Among these are role modeling, affirmations, self-assessment, self-reflection, and visualization.

Publicly share the value and content of communications in the e-mentoring community and the contributions of the mentors.

In DO-IT, we anonymously share content in discussions within the mentoring community in a column called The Thread, which regularly appears in the publication DO-IT News. We also publish Scholar, Ambassador, and Mentor profiles. You can review past issues of DO-IT News online. Articles about DO-IT participants that have appeared in the press can be found on the DO-IT Press page.

Monitor the workings of the e-mentoring community as it evolves. Adjust procedures and forms accordingly.

Formally and/or informally survey the mentors and young people in the community to assess their level of satisfaction with its workings and collect their suggestions for improvement. Assess the impact of participation in the e-mentoring community on reaching their academic, career, and independent living goals. Make appropriate adjustments.

Have fun!

Communication between participants in the electronic mentoring community should be enjoyable for everyone. Sharing humor and personal stories should be encouraged.