Presentation Summaries

People with Disabilities in Computing

Presenter: Richard Ladner

Computing fields need more people with disabilities because their expertise and perspectives spark innovation. By increasing access to include more people with disabilities in postsecondary and workplace settings, we allow a substantial group—15 percent of the world’s population—the ability to participate and create these innovations. Though there are many people with disabilities already succeeding in computing education and careers, these numbers are still much lower than their representation in the general population.

The World Health Organization defines disability not as a health problem, but by an individual’s ability to interact with the environment and the social barriers that prevent these individuals from fully participating in society. While K-12 education in the US has made great strides in including people with disabilities, only ten percent of college students and four percent of graduate students have disabilities.

Innovations that allow access to people with disabilities often become technology utilized by the wider population. Examples of this include personal texting, speech recognition, and video chat. Personal texting and picture phone were both originally created in the 1960’s for deaf people to communicate over distances; speech recognition was originally created for people who could not type easily. Many people now use these technologies daily (e.g., iOS’s Siri). Disability and technology innovation are intertwined, and more mainstream technology products have accessibility features built-in.

Barriers to access can be attitudinal as well as physical. Throughout the years, people with disabilities have been excluded, institutionalized, and eventually accommodated, which is still a reactive approach. We encourage a universal design mindset, a proactive approach that considers the needs of all people with varying levels of abilities from the beginning stages of design. This can include having multiple options so each student can learn and interact in the method that works best for them, as well as information technology that works with a wide range of assistive technologies.

Accessibility should be taught in all computing classes. Within the computing industry, there is demand for this knowledge and the innovation results from being proactive with regards to accessibility. Many companies are now requiring their employees to know accessibility principles and best practices. ABET, which sets the standards for engineering departments, now includes accessibility in their criteria.

To learn more about teaching accessibility, visit teachaccess.org. To learn more about various students with disabilities already studying and working in the computing field, visit the ChooseComputing profiles at AccessComputing Profiles.

Accommodations and Universal Design

Presenter: Sheryl Burgstahler

Ability exists on a continuum, where all individuals are more or less able to see, hear, walk, read print, communicate verbally, tune out distractions, learn, or manage their health. In K-12 education in the United States, every child is ensured a free, appropriate education in as integrated of a setting as possible. However, in postsecondary education, students must meet whatever course or program requirements apply and are offered reasonable accommodations as needed.

Accommodations and universal design (UD) are two approaches to access for people with disabilities. Both approaches contribute to the success of students with disabilities in computing classes. Accommodations are a reactive process, providing access for a specific student and arise from a medical model of disability. Students might be provided with extra time on tests, books in alternate formats, note takers, sign language interpreters, or other adjustments.

In contrast, UD is a proactive process rooted in a social justice approach to disability and is beneficial to all students. UD is designing products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design. A UD approach can benefit people who face challenges related to socioeconomic status, race, culture, gender, age, language, or ability.

UD of instruction is an attitude that values diversity, equity, and inclusion. It can be implemented incrementally, focuses on benefits to all students, promotes good teaching practice, does not lower academic standards, and minimizes the need for accommodations. UD can be applied to all aspects of instruction, including class climate, interactions, physical environments and products, delivery methods, information resources and technology, feedback, and assessment. Examples include the following:

- Arranging seating so that everyone has a clear line of sight.

- Avoiding stigmatizing a student by drawing undue attention to a difference.

- Using large, bold fonts with high contrast on uncluttered overhead displays and speak aloud all content.

- Providing multiple ways to gain and demonstrate knowledge.

- Avoiding unnecessary jargon; defining terms.

- Providing scaffolding tools (e.g., outlines).

- Providing materials in accessible formats.

- Providing corrective opportunities.

- Testing in the same manner in which you teach.

- Minimizing time constraints as appropriate.

Designing websites to include text alternatives for graphics, present context via text and visuals, include captions and transcripts for all video and audio content, ensure that all content and navigation can be reached with the keyboard alone, and spell out acronyms.

Educators who effectively apply UD and provide accommodations level the playing field for students with disabilities and make instruction welcoming to, accessible to, and usable by all students. They minimize, but do not eliminate, the need for accommodations.

Presentation and Discussion: How Can We Include Topics of Accessibility in the Computing Curriculum?

Presenter: Amy Ko, UW

When we talk about curricular change, it can start with an instructor changing how they teach a course. However, this change doesn’t just happen out of nowhere—it comes from faculty members thinking about what to teach their students and finding better ways to educate. There are many barriers to change, including curriculum that doesn’t need updating, faculty not having enough time, no room for more topics in the class, no room for more classes in the curriculum, or instructors who don’t have the expertise to teach a particular topic, like accessibility.

We hired three lecturers to teach Information 343: Client-Side Web Development, and I asked them to rework the existing curriculum to include accessibility. In order to do this, we trained these lecturers on web accessibility, and asked them to think of how they could include the information in their courses. Ultimately, one instructor realized they could redesign the lesson that covered markup to include information about web accessibility. This not only incorporated the information, but also served to make the lesson on markup more compelling. This instructor committed to teaching the new markup lesson over the summer. In order to encourage him, I checked in on a regular basis. This new lesson worked well and was engaging for students. Other instructors implemented this content subsequently. As a result, a year later we have trained 200 web developers who now know web accessibility basics.

Now, it isn’t always this easy to include accessibility topics within course curriculum. We had several things working in our favor:

- The iSchool has a strong culture of continuous improvement in learning outcomes and student engagement in the iSchool.

- We had a team of instructors already in the habit of improving their instruction every quarter reinforced these values.

- We focused on reaching out to lecturers whose only job was teaching and whose course load was structured to account for course improvement efforts.

- I was incentivized by my (funded) participation in AccessComputing to champion this change.

- The instructor creatively identified a weak part of the course material that could be improved with accessibility content.

- We modified content rather than adding new content.

- We identified an existing, required, well-liked course rather than proposing a new course.

- Accessibility is already taught in other courses throughout the undergraduate and graduate curricula, so it wasn’t viewed as a “new” topic.

- The instructors already had exposure to content from their professional experiences as software developers.

- Having an in-house accessibility expert made it easy to do a quick training, giving the instructors confidence in the material.

You can facilitate change by identifying a champion (whether this is you or someone else in your department), surveying your landscape for incentives and capacity for change, creating sufficient incentives and capacity, finding the person most motivated to change and manage their change, and repeating these steps as necessary. There should also be some long term thought to including accessibility, and adding scheduled time to check that the efforts put forward are not forgotten or waylaid.

I asked participants “How can we include topics of accessibility in the computing curriculum, and what are ways to incentivize and motivate faculty to include accessibility?” Their responses included the following:

- Some people know about accessibility and some people don’t—and if a professor doesn’t know anything about accessibility, they won’t teach it. Raising awareness and providing resources can mitigate this potential barrier.

- Looking at specific courses and making small changes to include accessibility in them.

- Bringing awareness to how accessibility is newly included in ABET accreditation standards may help to motivate faculty.

- Engaging tenure-track faculty who have the most power for encouraging curricular change.

- With more computing jobs requiring accessibility, motivate faculty by showcasing what companies are looking for and the tools students need to be successful in computing careers.

IT Accessibility: What Your Institutions Are Doing, and How You Can Help

Presenter: Terrill Thompson, UW

There are barriers at each step along the way of making IT accessible in computing courses. EDUCAUSE is a national organization focused on accessible IT within postsecondary education. This last year, I led a poster discussion that focused on students with disabilities sharing their experiences related to IT accessibility. Students shared their issues including inaccessible web-based programs, programs inaccessible to screen readers, inaccessible productivity tools, uncaptioned videos, and a variety of other problems. In higher education, if many of our programs, services, and activities are inaccessible due to these IT issues, it makes it monumentally harder for these students to succeed.

Each institution has tens or hundreds of thousands of web pages, digital documents, videos, and software applications that are inaccessible. For web pages, each page should follow WCAG 2.0 Level AA success criteria as well as Accessible Rich Internet Applications (ARIA), which provide a more interactive look at accessibility; however, very few web developers actually consider these when designing their webpages.

For documents, the tagged PDF has been around since 2001 with Adobe Acrobat 5.0, which makes it possible for a document to communicate the structure happening within the text (e.g., headings, alt text). However, making accessible PDFs can be difficult and most authors don’t know many accessibility techniques.

For videos, captions are extremely important for some people to access the information. While automatic speech recognition has improved, there are still many problems with relying on them to have the correct transcription. Furthermore, captioning has other benefits, including a searchable, interactive transcript, usability in quiet areas, and greater ease of access for non-native speakers of English. Videos may also need audio description for people with visual impairments.

Lastly, software is a wide topic with a lot of tricky issues. A growing number of institutions are adding accessibility requirements to their purchasing agreements, which push software developers to create more accessible products.

There are many civil rights complaints and lawsuits that have targeted postsecondary institutions regarding the accessibility of their IT. Their resolutions have brought to light five major points to address:

- Conduct an audit of the accessibility of IT and develop a corrective action strategy to address problems identified In the audit.

- Set institutional standards related to accessible technology.

- Provide training and education about accessibility to anyone on campus who is responsible for creating or procuring IT as well as those responsible for creating content.

- Institute procedures for addressing accessibility as a requirement with the procurement process.

- Provide and publicize a mechanism by which students, faculty, and staff can report accessibility issues on campus.

How can you help? Work at any level (state, institutional, college, departmental, or personal) to enact policies and procedures around creating accessible websites, documents, videos, and software. Consider research opportunities that address any of the problems described here. For more resources, visit www.uw.edu/accessibility.

Short Presentations: Teaching About Accessibility

Teach Access

Presenter: Matt May, Adobe

Accessibility is not commonly taught in the undergraduate computing curriculum. The problem is three-fold:

- There is too little accessibility talent in the pool, meaning that companies are left to train their own accessibility team.

- There is not a clear demand for accessibility talent in job descriptions, so few individuals study it in sufficient depth.

- There is a need for better, more uniform accessibility training.

All engineers, product testers, computer programmers need to be trained in accessibility in a uniform way, and companies need to be hiring for those specific accessibility requirements.

To help address this problem, a group of us have formed Teach Access, which currently has 29 partners, from education, industry, and the accessibility field. Teach Access’s first project was adding accessibility to job descriptions. Nine organizations committed to doing this and you can find sample language from their job descriptions on the Teach Access website. Our second project is a tutorial that provides basic accessibility training for developers and designers.

Our industry needs a lot of people who know a few things about accessibility and a few people that know a lot about accessibility. The former can be accomplished by including general accessibility and inclusive design training as part of general computing curricula. The latter can be accomplished by developing a standardized, advanced curriculum for teaching accessibility and inclusive design. What can industry offer to academia that will help cultivate more people who are interested and invested in accessibility? Teach Access is creating a plan, which includes qualified speakers to talk about accessibility, partnership opportunities (including internships, research projects, and fellowships), and learning tools and videos on accessibility.

To learn more about Teach Access and how to get involved, visit teachaccess.org, or email mattmay@adobe.com.

“The Accessibility Lecture”: Should We Teach Accessibility as a Standalone Topic or Integrate Disability Throughout the Course?

Presenter: Shiri Azenkot, Cornell University

I teach a class on interaction techniques (e.g., text entry and scroll bars). When designing this course, I had to consider constraints (time, curriculum requirements, and expectations) and how my course might compare to similar courses across institutions. Would I include accessibility into this course with an “Accessibility Lecture,” where I cover everything about accessibility in one short lecture or by integrating disability throughout the course?

An “accessibility lecture” might cover things like the definition and examples of disability, models of disability, the importance of accessibility, and interaction techniques for people with disabilities. Instead of covering the same topics on accessibility in a short amount of time, I integrated assistive technology and accessibility into multiple lectures as a part of the ongoing discussion. I included readings throughout the semester that discussed interaction techniques for people with disabilities and assistive technology. Furthermore, I tried to encourage my students to think about their biases they have based on perceived disability, age, race, gender, location, and a variety of other situations or statuses.

By incorporating disability throughout the course, accessibility becomes normalized and not marginalized. Disability also becomes included in context, and not just as a specialized subject, and means that students have more exposure to accessibility and disability-related issues. That being said, there are also advantages to a stand-alone “accessibility lecture.” It allows more time for framing the topic, drawing from disability studies, and motivating the importance of accessibility. This sort of lecture could also address other disability-related issues beyond interaction techniques. A combination of both approaches can enhance the content of a course.

How Designing for Users With and Without Disabilities Shapes Student Design Thinking

Presenter: Kristen Shinohara, UW

Despite the popularity of teaching design thinking, most technologies are not made to be accessible out-of-the-box. When students design, projects do not cover accessibility unless accessibility was directly included in the course syllabus and direction. Technology is often either designed for disability or ignores accessibility.

We came to ask how we could teach design thinking to incorporate accessibility in the design process and include accessible design as a key part of design thinking rather than a “special topic.” We taught an undergraduate course where students each designed in groups for expert users who had sensory disabilities. Students often came into this project with their own preconceived perceptions. By working on a project with a person with a disability, students soon changed their perceptions and confronted their biases. Furthermore, students discovered that many prototypes are inherently inaccessible and can not be used for user testing with individuals with disabilities.

Most students learned that designing with accessibility in mind was not as hard as they had thought, and most students felt very interested in including accessibility in all of their future projects, as well as designing for a wider range of user.

For more information, consult Shinohara, K., Bennett, C.L. and Wobbrock, J.O. (2016). How designing for users with and without disabilities shapes student design thinking. Proceedings of the ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS ‘16). Reno, Nevada (October 24-26, 2016). New York: ACM Press. ACM Digital Library.

UW Accessibility Capstone Course

Presenter: Anat Caspi, UW

All computer science and engineering students at the University of Washington are required to take a capstone course. Along with that capstone come certain expectations, including writing and documentation processes that must be in place.

The course provides students with exposure, engagement, and participation and interaction:

Exposure to the engineering, design, economic and social challenges facing designers, engineers, researchers, entrepreneurs, clinicians, older adults, and individuals with disabilities in the design, development, and use of accessible technology

Engagement in a team-based project experience that exercises collaborative working skills and applies an engineering design process to tackle difficulties experienced by individuals with disabilities and older adults

Participation and Interaction with users of accessibility features and assistive technology in the local community along with health care professionals, coaches, and caregivers.

It also gives students more opportunities to

- think critically about the complex relationship between technology and diverse abilities;

- communicate effectively about diverse abilities and about design process through interviews with Need Experts, in-class discussions, report writing, project presentations and media production; and

- apply design and engineering skills to create technology solutions that increase independence and improve quality of life for people of all abilities.

Improving a Web Accessibility Class Curriculum

Presenter: Anna Marie Golden, UW

I teach a web accessibility class at Bellevue College. The first time I taught the class I questioned the curriculum’s focus. The class meets three times for three hours per session. The second session was all about legal cases. I thought we were doing students a disservice with this focus because when they go on a job interview, they won’t be asked about specific legal cases; they will be asked about creating accessible web content.

When I presented this material to my class, I told them I didn’t expect them to remember all of the cases. I told them the important thing to note is that this has been a really long process and we still aren’t there yet. When thinking about all of the cases, the thing to keep in mind is what the outcomes were. I told them to think about the issues and how the courts resolved them.

After I taught the class for the first time I went to administrators at Bellevue College and asked them about revising the curriculum. I told them the current curriculum is doing students a disservice because the focus should be on how to create accessible content and not all about legal cases. They were receptive to my ideas and I received the okay to revise the curriculum.

I also wasn’t enthused about the curriculum material for the first class session. It included empathy-building exercises. I questioned the authenticity these exercises would bring but in reading student evaluations after the class had ended, I learned students actually liked this exercise and appreciated what they had learned from it. Therefore I found value in the exercises and decided to continue with them.

So the next time I teach the course, the second session will be different. Instead of spending the full time discussing legal cases, we are actually going to talk about the things students can do to create accessible web content. These are the skills they need to ensure they are creating accessible websites.

Short Presentations: Working with Students with Disabilities

Including Students with Disabilities in Summer Programs

Presenter: Sarah Lee, Mississippi State University

Bulldog Bytes is a K-12 summer outreach program based at Mississippi State University. Through hands-on learning and industry speakers, students demonstrate knowledge of cybersecurity vulnerabilities, cybercrime, and how attention to safe online behavior is crucial to their personal safety. Last summer we had over 80 participants and a sizeable support team, including near-peers and college-age mentors, and utilized a wide variety of programming tools.

We’ve hosted interns with disabilities through the AccessComputing program. By hiring students with disabilities, we’ve provided opportunities for computing majors with disabilities and we’ve seen increased student confidence and relationship building among both the participants with disabilities and those without. Students saw people from underrepresented group in leadership positions, which helps encourage others from underrepresented groups to apply and succeed in challenging programs. Interns reported increased confidence from serving in a leadership position and learning more about conducting outreach activities.

Multi-Modal Lecturing Helps All to Learn

Presenter: Vincent Martin, Georgia Tech

People with disabilities all perceive information differently, depending on when they were born and when they developed their disability. People sense and perceive the world in multiple ways; while we are often taught there are only five senses, there are actually 12 to 15 senses. Learning can involve all of these senses.

Learning styles are different methods that people learn; the three main methods described are visual, auditory, and kinesthetic. However, people can learn to learn in a variety of ways. For example, people who think they learn only visually can actually be shown how to learn auditorily through multi-modal exercises.

All classes should use multi-modal learning because you never know how someone is engaging with the materials. Regardless of a person’s disability or where they lie on the spectrum of ability, multi-modal lecturing is an example of an application of universal design.

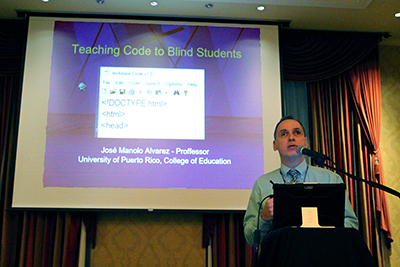

Teaching Coding to Blind Students

Presenter: Jose Alvarez, University of Puerto Rico

Most individuals who are blind access their computer with a screen reader for output and a keyboard for input. To program, they use coding editors, such as text editors or graphical user interfaces (GUIs). In order to be accessible to individuals who are blind, these applications need to work with a screen reader as well as work solely with keyboard commands. Unfortunately, this is not the case with many applications.

To be successful in computing, individuals who are blind, like individuals who are sighted, need to develop computational thinking skills. Applications and games that are designed to do this are often inaccessible to blind students as well. Video games are usually graphic, but it is possible for them to be designed to be accessible auditorily. Games can be designed so that a screen reader can read movements in the game and cue the player to what is happening. I have designed games that include an accessible blackjack game, math-based baseball, and an accessible driving game.

Accessible applications should be the norm for all educational topics to help students learn and stay engaged. Learn more at www.fundacionmanolonet.org.

Accessible Presentations

Presenter: Kyle Rector, University of Iowa

Making presentations accessible is important in multiple settings – including in the classroom and at conferences. The first thing you should do to make your presentation accessible is to submit slides a few days in advance in an accessible format to allow those who need them to view the slides beforehand. For the actual presentation itself, slides should be made with a high contrast color scheme and use more than just color to communicate information. Furthermore, text should be kept brief so viewers don’t get lost in reading bullets rather than listening to the speaker. One exception to this could be an entire quote; in that case the entire quote should be read out loud.

Graphics should be kept simple so viewers aren’t trying to figure out the meaning of the graphic. I recommend simple graphics that are black and white from thenounproject.com. Furthermore, all images should be verbally described and have a purpose within the presentation. Avoid using animations as much as possible, and all videos incorporated into presentation should have captions and verbal description.

Make sure to speak clearly when presenting. Everyone in the room needs to understand what you’re saying, including interpreters, captioners, and people who may not speak English as a first language. Speak in a proper cadence, face the audience, speak loudly, and use understandable words. A version of this presentation can be found on YouTube at www.youtube.com/watch?v=L9TxhGv91kc.

Runestone Interactive

Presenter: Jeff Rick, Georgia Tech

Runestone Interactive is an open source e-book project focused on computer science education. It supports authors with an open source, cross-platform toolkit, mark-up text authoring, and the ability to compile locally before transferring to a server. It supports students with interactive content and immediate feedback, and it supports faculty by providing tools for managing courses, tracking student performance, and providing free hosting.

The program integrates a variety of supports, including the ability to code in a browser and a tool called CodeLens that shows how code is executed. There are also the Parsons Problems, which are puzzles that allows students to drag and drop blocks of code to successfully solve a problem.

Runestone Interactive has 71,000 users, more than 730 courses run, with 240 current running courses. Over 20,000 users access these courses each day. There are 12 completely open-source books available on the site.

In the future, there will be more sophisticated administrator tools, more accessible content and platform use, and more content. To get started with your own course, visit the site at runestoneinteractive.org, or get involved by becoming a part of the community and working on the platform itself.