Part I: Creating an Electronic Mentoring Community

PART I of this book, comprising Chapters One through Four, addresses the philosophy and purpose of online mentoring. It tells how to design an electronic mentoring community, recruit and train participants, promote online discussion, and begin to explore the topics of success and self-determination.

The entire content of this book can be found at at the titular page of this book. Use this electronic version to cut, paste, and modify appropriate content for distribution to participants in your electronic community; please acknowledge the source.

Chapter One provides an introduction to the philosophy and purpose of online mentoring and explores its benefits to participants. Along with the complementary video, DO-IT Pals: An Internet Community, this chapter shares the model of the DO-IT online community.

Chapter Two explains a step-by-step process for setting up an online mentoring community where young people are supported by caring adults. A complementary video, Opening Doors: Mentoring on the Internet, reinforces basic mentoring concepts and methods and documents the value of online mentoring for both mentors and protégés. How DO-IT Does It provides the context in which an electronic mentoring community is employed as a strategy to promote the success of people with disabilities.

Chapter Three addresses orientation and training to help new mentors prepare for the unique challenges of online mentoring. It includes email messages for mentors, as well as guidelines to send to new protégés regarding communication and Internet safety.

In Chapter Four mentors and protégés begin to explore the topics of success and self-determination. Five stories of success and self-determination are presented in the video series Taking Charge: Stories of Success and Self-Determination. This chapter introduces the content explored in depth in PART II of the book.

Chapter One

An Introduction to E-mentoring and E-communities

No country, however rich, can afford the waste of its human resources.

— Franklin D. Roosevelt —

Individuals with disabilities experience far less career success than their peers who do not have disabilities; however, differences in achievement diminish significantly for those who participate in postsecondary education (Blackorby & Wagner, 1996; Stodden & Dowrick, 2000; Yelin & Katz, 1994). College graduates with disabilities achieve success in employment close to that achieved by those without disabilities. Although the rate of participation in higher education is lower for people with disabilities than it is for people without disabilities, this difference is diminishing (Henderson, 2001; National Council on Disability, 2000).

A bachelor's degree or higher is a prerequisite for many challenging careers, including high-tech fields in science, engineering, business, and technology. Few students with disabilities pursue postsecondary academic studies in these areas, and the attrition rate of those who do is high (National Science Foundation, 2000; Stodden & Dowrick, 2000).

Lack of job skills and related experiences also limit career options for people with disabilities (Colley & Jamieson, 1998; Unger, Wehman, Yasuda, Campbell, & Green, 2001). They also have little contact with other people with disabilities and, thus, limited access to positive role models with disabilities (Seymour & Hunter, 1998).

Low expectations of and lack of encouragement from those with whom they interact can impede the realization of the full potential of people with disabilities in challenging fields. Support systems in high school are no longer available after graduation, and many students with disabilities lack the self-determination, academic, and independent living skills necessary to make successful transitions to college and careers (National Information Center for Children and Youth with Disabilities, 1999).

Youth with disabilities more often continue to live with their parents or in other dependent living situations after high school than their peers without disabilities. They also engage in fewer social activities. The effect of social isolation can be far-reaching, affecting not only personal well-being but also academic and career success (Seymour & Hunter, 1998).

The lives of some people with disabilities demonstrate that they can overcome challenges imposed by inaccessible facilities, curriculum materials, equipment, and electronic resources; lack of encouragement; and inadequate academic preparation and support (American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2001; National Center for Educational Statistics, 2000; National Council on Disability and Social Security Administration, 2000). Steps to careers for students with disabilities include preparing for, transitioning to, and completing a college education; participating in relevant work experiences; and transitioning from an academic program to a career position.

Research studies have identified successful practices for bringing students from underrepresented groups into challenging fields of study and employment. They include the provision of:

- technology

- programs that bridge between academic levels and between school and work

- work-based learning opportunities

- peer support

- mentoring

In this chapter, strategies developed in DO-IT's award-winning online mentoring community are shared so that you can apply successful practices in your program.

Acknowledgement: Much of the content of this chapter is published in earlier work (Burgstahler, 1997, 2003b, 2006a; Burgstahler & Cronheim, 1999, 2001; DO-IT, 2005).

Peer, Near-Peer, and Mentor Support

Most of us can think of people in our lives who supplied information, offered advice, presented a challenge, initiated a friendship, or simply expressed an interest in our development as a person. Without their intervention we might have remained unaware of a resource, neglected to consider an exciting opportunity, progressed toward a goal at a slower pace, or given up on a goal altogether.

Supportive relationships with peers and adults can positively impact the transition period following high school when a student's structured environment ends and precollege support systems are no longer in place. Within social support systems, participants provide what has been defined as communication support behavior, "whereby individuals within a formal social system offer and receive information and support from one another in a one-way or reciprocal manner" (Hill, Bahniuk, Dobos, & Rouner, 1989, p. 356).

Mentor Support

The term mentor comes from Homer's Odyssey, in which a man named Mentor was assigned the task of educating the son of Odysseus. Protégé (or mentee) refers to the person who is the focus of the mentor's efforts. Mentoring has long been associated with a variety of activities including counseling, role modeling, job shadowing, advice-giving, and networking.

Young people with disabilities can be positively influenced by observing role models with similar disabilities successfully pursuing education and careers that they might otherwise have thought impossible for themselves. Mentors can help their protégés explore career options, set academic and career goals, examine different lifestyles, develop social and professional contacts, identify resources, strengthen interpersonal skills, achieve higher levels of autonomy, and develop a sense of identity and competence. Information, guidance, motivation, resources, and emotional support provided by mentors can help young people successfully transition from high school into the less structured environments of postsecondary education, employment, and community living.

Protégés report benefits of mentoring to include

- better attitudes toward school and the future,

- decreased likelihood of initiating drug or alcohol use,

- greater feelings of academic competence,

- improved academic performance, and

- more positive relationships with friends and family (Campbell-Whatley, 2001).

Protégés are not the only ones who benefit from mentoring relationships. Adults can also find satisfaction in their helping roles. Common positive effects for mentors include

- increased self-esteem,

- feeling of accomplishment,

- insights into childhood and adolescence, and

- personal gain, such as increased patience, a sense of effectiveness, and the acquisition of new skills or knowledge (Rhodes, Grossman, and Resch, 2000).

In summary, "mentoring is a win-win situation. Young people win, adult volunteers win. It is, quite frankly, society at large that is eventually the real winner" (Saito & Blyth, 1992, p. 60).

Group Mentoring

At least in part because of a shortage of available adult mentors, group mentoring programs have emerged. Typically, in this model one mentor is assigned to a small group of young people. In group mentoring, mentors cannot provide as much individual attention to each young person as they might in the traditional one-to-one model, but positive outcomes can also be achieved as a result of participant interactions. Although, as with one-to-one mentoring, most group mentors want to develop personal relationships with protégés, they also promote positive peer interactions. Participants report that group mentoring helps them improve social skills, relationships with individuals outside of the group, and, to a lesser extent, academic performance and attitudes (Herrera, Vang, & Gale, 2002; Sipe & Roder, 1999).

Peer and Near-Peer Support

Peers can offer some of the same benefits to young people as mentors. Like mentors, peers can coach and counsel, offer information and advice, provide encouragement, act as sounding boards, function as positive role models, and promote a sense of belonging. Peers of the same age offer unique opportunities for sharing, are easier for participants to approach than adult mentors, and typically develop relationships that are longer lasting than those established with adults. While mentoring relationships are primarily one-way helping relationships, peer relationships offer a higher degree of mutual assistance, with both individuals giving and receiving support. Peers facing similar challenges related to their disabilities can share strategies to overcome disability-related barriers.

Relationships with individuals who are a year or two older than protégés, sometimes called near-peers, offer a powerful combination of the benefits of peer and mentor relationships. Near-peers and protégés can discuss issues such as whom on campus to tell about a disability, how to communicate with professors about accommodations, how to live independently, and how to make friends. In addition, near-peers can become empowered as they come to see themselves as contributors and role models.

Computer-Mediated Communication

Mentor, peer, and near-peer relationships have the potential to provide students with disabilities with psychosocial, academic, and career support, thereby lessening or eliminating some of the unique challenges they face. However, these types of relationships can be limited by physical distance, time, and schedule constraints and, in some cases, disability-related communication barriers (e.g., speech impairments, deafness).

For these relationships to be successful, it is often necessary to match young people and mentors who are in close geographic locations. Even if such relationships can be established, communication, transportation, and scheduling problems must be resolved. In short, arranging traditional in-person mentoring and peer support for this population is problematic.

Computer-mediated communication (CMC), wherein people use computers and networks to communicate with one another, makes communication across great distances and different time zones convenient, eliminating the time and geographic constraints of in-person communication. CMC facilitates the development of communities for people with common interests, regardless of their physical locations. Using electronic mail, text messaging, chat rooms, web-based forums, and other technology to sustain meaningful relationships between people who are geographically disconnected allows us to reconsider the concept of community as a physical location. The lack of social cues and social distinctions like gender, age, disability, race, and physical appearance in CMC can make even shy participants willing to share their views.

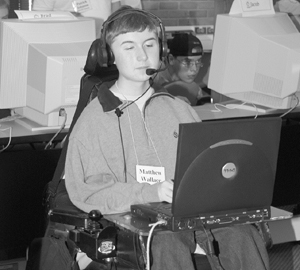

The development of computers and assistive technology makes electronic communication possible for all individuals, regardless of disability. For example, a person who is blind or has a disability that makes reading difficult can use text-to-speech software to read aloud text presented on a computer screen. An individual with limited use of his hands can use a trackball, a headstick, speech input, or an alternative keyboard to control the computer; and a person with a speech or hearing impairment may be able to participate more fully in communications when they are conducted electronically.

E-Mentoring Communities

Online discussion groups, chat rooms, web-based forums, and other CMC vehicles have emerged as popular tools for interaction between individuals within groups. When CMC is the mode for communication between mentors and their protégés, it has been called e-mentoring, online mentoring, or telementoring. As in traditional on-site mentoring, the mentor, often an adult, develops a close relationship with a younger person in order to promote his or her well-being and success.

One advantage of an online mentoring community (or electronic mentoring community, or e-community), as compared to more traditional one-to-one electronic mentoring, is that mentors observe the communications of other mentors as well as the responses of all of the young people in the community. In this format, once basic guidelines are provided, mentors learn effective mentoring techniques on the job. They can also more effectively and efficiently share their expertise and insights, since no individual is responsible for providing all mentoring communications with a specific protégé in the community. With this approach, each participant benefits from the expertise of a group of mentors, peers, and near-peers.

DO-IT's E-Mentoring Community

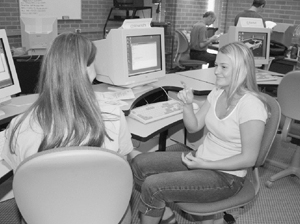

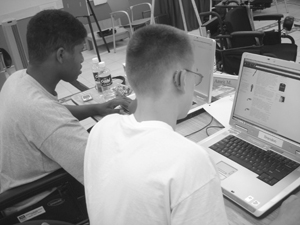

In DO-IT programs, mentor, peer, and near-peer support sometimes occurs in person, but most of the time is delivered through its e-mentoring community. Participants are mentored within a group, and many contributors are included in interactions. Participants also disseminate academic and career-enhancing resources that benefit all community members. Positive aspects of DO-IT's e-community approach include the following:

- Individuals benefit from the experiences of a large group of mentors, peers, and near-peers.

- Mentors can specialize in the areas of their strongest expertise.

- The program performs successfully even though some mentors are less available and skilled than others.

- Using asynchronous, text-based communication on the Internet eliminates barriers faced by other forms of communication that are imposed by location, schedule, and disability.

- The program administrator views all group communications that take place, thus finding it easy to guide and contribute to conversations.

- Mentors learn techniques from each other by attending to the communications that take place.

Most DO-IT Mentors are college students, faculty, engineers, scientists, or other professionals who have disabilities. Protégés are participants in the DO-IT Scholars and DO-IT Pals programs (DO-IT, 2006a,c; Burgstahler, 2007). These students are making plans for postsecondary education and careers. They all have disabilities, including vision, hearing, mobility, and health impairments and specific learning disabilities. Frequent electronic communications and personal contacts bring DO-IT protégés, near-peers, and mentors together to facilitate academic, career, and personal achievements.

Introducing protégés to DO-IT Mentors with similar disabilities is a strength of DO-IT's program. One protégé reported she had never met an adult with a hearing impairment like hers before getting involved in DO-IT: "But when I met him, I was so surprised how he had such a normal life, and he had a family, and he worked with people who had normal hearing. So he made me feel a lot better about my future."

DO-IT's E-Mentoring Participants

DO-IT Scholars

High school students with disabilities who are accepted into the DO-IT Scholars program communicate electronically with Mentors and other DO-IT participants using computers and, if necessary, assistive technology. DO-IT Scholars who do not have the necessary technology are loaned equipment and software. DO-IT Scholars attend summer programs at the University of Washington in Seattle where they participate in academic lectures and labs, live in residence halls, and practice skills that will help them succeed in college and career settings.

DO-IT Ambassadors

When DO-IT Scholars graduate from high school and move on to postsecondary studies, they can become DO-IT Ambassadors, sharing their experiences and advice with DO-IT Scholars and DO-IT Pals and otherwise promoting DO-IT goals.

DO-IT Pals

Teens with disabilities who want to go to college and who have access to the Internet can apply to become DO-IT Pals. DO-IT Pals come from all over the world and use the Internet to explore academic and career interests and communicate with DO-IT Scholars, Ambassadors, and Mentors. To become a DO-IT Pal, a teenager with a disability who already has access to the Internet must send email to doit@u.washington.edu.

DO-IT Mentors

Adult Mentors are an important part of the DO-IT team. DO-IT Mentors are college students, faculty, and professionals in a wide variety of career fields. Many DO-IT Mentors have disabilities themselves. Mentors support DO-IT Scholars, Ambassadors, and Pals as they transition to college, careers, and self-determined lives.

DO-IT Staff

The e-mentoring community administrator monitors discussions, introduces new members to the group, and sends messages with mentoring tips to the mentors and lessons and activities to all members of the community. Other staff join in discussions, particularly during times of low participation by others, and send useful information and resources.

DO-IT e-community participants learn strategies for success in academics and employment. Mentors provide direction and motivation, instill values, promote professionalism, and help protégés develop leadership skills. As one DO-IT Scholar noted, "It feels so nice to know that there are adults with disabilities or who know a lot about disabilities, because I think that people who are about to go to college or start their adult life can learn a lot from mentors . . ." As DO-IT Scholars move from high school to college and careers, they too, as DO-IT Ambassadors, become mentors and role models, sharing their experiences with younger participants.

There are probably as many mentoring styles as there are personality types, and no one can be everything to one person. Each DO-IT participant benefits from contact with many mentors, peers, and near-peers. One-to-one relationships develop naturally as common interests are identified by pairs of mentors, protégés, peers, and near-peers. DO-IT also facilitates communication in small groups through the use of electronic discussion lists. For example, one group includes Mentors, protégés, and near-peers who are blind. Participants in this group discuss common interests and concerns such as independent living, speech and Braille output systems, and options for displaying images and mathematical expressions.

While most communication occurs electronically, some Mentors and near-peers meet DO-IT Scholars during DO-IT Summer Study programs on the University of Washington Seattle campus and at other DO-IT activities across the United States. In-person contact strengthens relationships formed online.

DO-IT has been studying the nature and value of electronic mentoring since 1993. Thousands of electronic mail messages were collected, coded, and analyzed; surveys were distributed to DO-IT Scholars and Mentors, and focus groups were conducted (Burgstahler & Cronheim, 2001).

Findings suggest that computer-mediated communication can be used to initiate and sustain peer-peer and mentor-protégé relationships and alleviate barriers to traditional communications due to time and schedule limitations, physical distances, and disabilities of participants. Both young people and mentors actively communicate on the Inter-net and report positive experiences in using the Internet as a communication tool.

The Internet gives these young people support from peers and adults otherwise difficult to reach, connects them to a rich collection of resources, and provides opportunities to learn and contribute. Participants note benefits over other types of communication. They include the ability to communicate over great distances quickly, easily, conveniently, and inexpensively; the elimination of the barriers of distance and schedule; the ability to communicate with more than one person at one time; and the opportunity to meet people from all over the world. Many report the added value that people treat them equally because they are not immediately aware of their disabilities. Negative aspects of electronic communication include difficulties in clearly expressing ideas and feelings, high volumes of messages, and occasional technical difficulties.

DO-IT's online program has received national recognition with its 1997 Presidential Award for Excellence in Mentoring "for embodying excellence in mentoring underrepresented students and encouraging their significant achievement in science, mathematics, and engineering." It also received the National Information Infrastructure Award in 1995 "for those whose achievements demonstrate what is possible when the powerful forces of human creativity and technologies are combined." Research results suggest the success of the DO-IT electronic community in promoting positive college and career outcomes (e.g., Burgstahler, 1997, 2001, 2002b, 2003a; Burgstahler & Cronheim, 2001; Kim-Rupnow & Burgstahler, 2004). But more importantly, the DO-IT electronic mentoring community has documented its value in the successful lives of its participants and the willingness of those who were once protégés to support young people in the community as they were supported in their youth.

The findings of research on DO-IT's e-mentoring community suggest that peer-peer and mentor-protégé relationships on the Internet perform similar functions in providing participants with psychosocial, academic, and career support. However, each type of relationship has its unique strengths. For example, peer-peer communication includes more personal information than exchanges between mentors and protégés.

Building on the successes of DO-IT and other online mentoring programs, practitioners should consider using the Internet as a vehicle for developing and supporting positive peer and mentor relationships.

Contributions of DO-IT Participants

Everyone in the DO-IT electronic mentoring community benefits from participation. DO-IT Mentors and near-peers in their mentoring role offer protégés

- Information—Mentors share their knowledge and experiences.

- Contacts—Mentors introduce their protégés to valuable academic, career, and personal contacts.

- Challenges—Mentors stimulate curiosity and build confidence by offering new ideas, strategies, and opportunities.

- Support—Mentors encourage growth and achievement by providing an open and supportive environment.

- Direction—Mentors help protégés discover their talents and interests and devise strategies to attain their goals.

- Advice—Mentors make suggestions to help protégés reach academic, career, and personal goals.

- Role Modeling—Mentors let protégés know who they are and how they have reached their goals.

DO-IT protégés offer Mentors

- Challenge—Mentors develop their own personal styles for sharing their skills and knowledge via electronic communication.

- Opportunities to Help Set Goals—Mentors encourage DO-IT participants to listen to their hearts and think about what they really want to do.

- A Chance to Share Strategies—Mentors pass on hard-earned experiences.

- New Ideas—Mentors join an active community of talented students and professionals with a wide range of disabilities who are eager to share their own strategies for problem solving and success.

- Fun—Mentors share in the lives of motivated young people, listening to them, hearing about their dreams, helping them along the road to success—it's fun!

Joining an Existing Online Mentoring Program

As is apparent by the size of this book, it takes a great deal of time and effort to develop and support your own electronic mentoring community. Steps involved are outlined in the following chapter. If you do not have the resources to make this commitment, consider finding an existing community to join. For example, DO-IT hosts an electronic community for teens with disabilities, near-peers, and mentors. DO-IT Scholars, Ambassadors, and Mentors are members. In addition, any teen with a disability who plans to go to college can apply to join the community as a DO-IT Pal. DO-IT Pals receive peer, near-peer, and mentor support, as well as access to a rich collection of resources. Teens with disabilities can simply send an email message to doit@u.washington.edu to join DO-IT Pals. More information about this program can be found in the video DO-IT Pals: An Internet Community, and the accompanying brochure, DO-IT Pals. They can be found on the DO-IT Pals page or purchased from DO-IT.

Other online mentoring options for students with disabilities can be found in the DO-IT Knowledge Base article Are there electronic mentoring programs for students with disabilities?

Just DO-IT!

Whether you mentor a young person, connect one child with a caring adult, create a small mentoring group in your church or school, develop an elaborate electronic mentoring community, or encourage young people to join an existing online mentoring program, find ways to make mentoring a part of the lives of the young people with whom you interact.

The next chapter tells you how to create an electronic mentoring community. The chapters that follow provide mentoring tips and activities that can be adapted for any mentoring environment.

Chapter Two

Steps to Creating an E-mentoring Community

We make a living by what we get. We make a life by what we give.

— Sir Winston Churchill —

Creating an online mentoring community requires access to technology and Internet communication tools, administrative infrastructure, and ongoing facilitation. Following are steps for setting up your own e-mentoring community for teens with examples from the successful practices employed by DO-IT. Sample forms and documents that can be modified to suit your program are provided in Chapter Thirteen.

View the video Opening Doors: Mentoring on the Internet, for an overview of DO-IT's electronic mentoring community, as well as for testimonials from participants. To understand the program context of this e-mentoring community, view the video How DO-IT Does It. These video presentations can be purchased from DO-IT in DVD format or freely viewed on the DO-IT Video page. Consider what goals, characteristics, and outcomes of DO-IT's e-mentoring community you hope to tailor to your program.

Acknowledgement: A summary of these steps is published as an Information Brief by the National Center Secondary Education and Transition (Burgstahler, 2006b).

Establish clear goals for the program.

The ultimate goal for DO-IT participants is a successful transition to adult life. In DO-IT's supported community, participants prepare for college and employment, develop social competence, learn to use the Internet as a resource, reflect on their own experiences, practice self-determination and leadership skills, and learn from others.

Decide what technology to use.

Email coupled with electronic distribution lists, message boards, web-based forums, and chat rooms are all possibilities for supporting peer and mentor interactions. Chat and other synchronous methods require that participants be on the same schedule; this condition is too restricting for most programs. In addition, these systems are not accessible to all students, in particular to those who are very slow typists. Web-based forums are a possibility, but they require that students and mentors regularly enter the message system to participate, thus all participants must have both the motivation and the discipline to regularly access the system, and this is not true of all teens.

DO-IT has been successful with using electronic mail and distribution lists to maintain its electronic mentoring community. This text-based asynchronous approach is fully accessible to everyone and results in messages appearing in participant email inboxes. As long as they regularly access their email, it is difficult for students and mentors to ignore the conversations that occur. Guidance to participants regarding how to manage email correspondence (e.g., using folders, deleting old messages) is provided as part of participant training.

If you are interested in setting up a distribution list ask your Internet service provider if it has the capability to do this. Also explore web-based options such as those provided by topica and yahoo. All of these options forward to all members of a list any email messages sent to the list address. Assign the participants to distribution list(s) that are closed; in other words, individuals cannot become part of the community without going through the application process managed by the administrator.

Select only universally-designed technology to use for communication in your community. This means that it is fully accessible to all potential participants, including those who have disabilities. Make sure that a person who is deaf or who has a speech impairment can participate in all communications. Technology you choose should also be fully accessible to individuals who are blind and using text-to-speech adaptive technology as part of their computer system. Consult DO-IT's website on Accessible Technology for more information about accessible technology.

Establish a Discussion Group Structure.

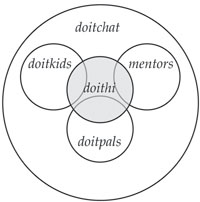

When DO-IT had only a small number of participants, there were two e-mentoring community discussion lists, doitkids@u.washington.edu for the DO-IT Scholars and mentors@u.washington.edu for the Mentors. Mentors could communicate with each other on the mentors list, and teens could communicate with each other on the doitkids list. Messages were sent to both addresses simultaneously for conversations that included all Mentors and Scholars, like those labeled E-Community Activity in the remaining chapters of this book. When the DO-IT Pals program emerged, we created a list for these participants, doitpals@u.washington.edu. To better facilitate large-group discussions we eventually set up a distribution list, doitchat@u.washington.edu, that includes all of the members of doitkids@u.washington.edu, mentors@u.washington.edu, and doitpals@u.washington.edu. Discussions that include the full e-community take place on the doitchat list.

As the DO-IT community grew in size, individuals expressed an interest in continuing with large group conversations but also communicating in smaller groups with people whose accommodation strategies are similar to their own. To address this need, we set up several more discussion lists. For example, doithi@u.washington.edu was set up for mentors, near-peers, and protégés who have hearing impairments. Members of this list discuss topics that might not interest the larger community, such as sign language interpreters, FM systems, and cochlear implants. The figure above illustrates how individuals in the doithi group are drawn from members of the other groups.

Similarly, special distribution lists were set up for individuals with visual impairments, learning issues, and other classifications. A lead mentor and at least one DO-IT staff member is included on each distribution list to facilitate communication and to assure that all messages are appropriate.

Example of the DO-IT Discussion List Structure for Participants with Hearing Impairments.

Each doithi member is also a member of doitchat and one of the groups doitkids, doitpals, and mentors.

Select an administrator for the e-mentoring community, and make other staff and volunteer assignments as needed.

The DO-IT electronic community promotes communication in group discussions that involve many mentors, near-peers, and protégés. However, to maximize participation in large communities, it is important to assign each protégé to a specific mentor who will assure the participant's regular involvement and satisfaction, but not limit his/her communication with others. For greater assurance of follow-through, it is desirable for these mentors to be paid staff. In DO-IT, for example, all DO-IT Scholars and Ambassadors are assigned to key staff members who communicate with them personally on a regular basis.

To assure supervision of lead mentors and coordination with other staff, an e-community manager was assigned. This role also includes obtaining the informed consent of parents as well as the collection and dissemination, to appropriate groups, of web resources and other information of specific interest. Other staff assignments include technical support (e.g., subscribing individuals to the distribution list and correcting email address errors) and mentoring leads for subgroups of the mentoring community.

Develop guidelines for protégés concerning appropriate and safe Internet communications.

Relationships developed with mentors become channels for the passage of information, advice, opportunities, challenges, and support, with the ultimate goals of facilitating achievement and having fun. Keep in mind that, although the majority of Internet resources and communications are not harmful to children, participants may stumble into situations or be encouraged to participate in communications that are inappropriate. They may encounter objectionable material by innocently searching for information with a search engine or mistyping a web address. On the Internet, they might:

- see materials that include content that is sexual, violent, hateful, or otherwise inappropriate for children

- be exposed to communications that are harassing or demeaning and, perhaps, even be drawn into these types of conversations themselves

- be encouraged to participate in activities that promote prejudice, are unsafe, or are illegal

- meet a predator who uses the Internet to develop trusting relationships with kids and then arranges to meet them in person

- make unauthorized purchases using a credit card

Teenagers are particularly vulnerable to being exposed to material and engaging in activities that are inappropriate. This is because they are more likely than younger children to use computers unsupervised; have the skills to conduct searches on the Internet; participate in online discussions via email, chat, instant messaging, or bulletin board systems where inappropriate communications can occur; and have access to credit card information.

If your electronic community includes young people under the age of eighteen, obtain the informed consent of parents or guardians, making the risks and benefits of using the Internet clear. Sample content for a permission form for parents or guardians to sign is included in Chapter Thirteen of this book. Seek advice from legal experts in your organization or community as you explore ways to keep participants safe.

Establish rules for participation in your community, and distribute them to the participants and mentors. Appropriate rules depend upon the ages of participants and the nature of the community. Consider adopting a set of expectations similar to Kids' Rules for Online Safety, published at SafeKids.com. Tailor them for your participants and encourage families to post them near Internet-connected computers in their homes. The guidelines should include your expectations for participation in the community (for example, check messages each week), child safety issues, and a statement that tells young participants to inform their parents and the e-community administrator if they receive email that is inappropriate or makes them uncomfortable. Sample guidelines can be found in Chapter Thirteen of this book.

Establish roles and develop guidelines, orientation, and training for mentors.

Determine what roles you desire mentors to perform in the program. Then develop guidelines for mentors, as well as program goals and operations that are consistent with these roles. The guidelines should be simple and straightforward and shared with potential applicants so that they understand mentor responsibilities.

Decide in what form(s) orientation and training should occur. The optimal amount of training depends on the complexity of your program and the expected roles of mentors. It is best if the training is interactive and engaging. Topics covered in the orientation should include

- an overview of how communication is to occur. In the case of DO-IT, an email message is sent to a specific discussion list or to an individual.

- an outline of the responsibilities, expectations, and boundaries your program has developed for both mentors and protégés.

- general mentoring tips, as well as tips designed to teach mentors how to promote success, self-determination, and problem solving skills.

- information to improve skills such as effective communication strategies and email netiquette.

- resources for mentors, such as additional mentor training, disability information, education, and career development.

See Chapter Three for more information on mentor orientation and training.

Standardize Procedures for Recruiting and Screening Mentor Applicants.

Consider what recruiting methods and screening devices will be used to choose mentors. Written applications, personal interviews, reference checks, and criminal record checks should be considered. Make sure that the application packet addresses the orientation, motivation, and skills needed to perform mentoring roles and includes established mentoring guidelines. Assign one staff member to review the application packet and to call references. Consider having a panel make final decisions on selections.

In DO-IT, mentoring opportunities are communicated by word of mouth through organizations with which DO-IT has connections. This approach helps assure the quality of mentors and the safety of participants. We provide prospective mentors with an application form that includes questions similar to those in the Sample Mentor Application in Chapter Thirteen of this book. For further suggestions on recruiting mentors, consult Recruiting Mentors: A Guide to Finding Volunteers to Work with Youth at www.ppv.org/ppv/publications/assets/28_publication.pdf.

Determine how to recruit protégés.

Decide how best to recruit participants to your program. In DO-IT, information about the DO-IT Scholars and DO-IT Pals programs is regularly distributed to schools, parent groups, and organizations that come in contact with teens who have disabilities. Teenagers submit application materials to join the competitive DO-IT Scholars program. An advisory board selects Scholars by reviewing their applications, teacher recommendations, parent recommendations, and school records. In the DO-IT Pals program, potential participants submit a short online application to doit@u.washington.edu; if they meet the basic criteria, they are included in the electronic community as DO-IT Pals. When individuals are accepted into the DO-IT Scholars and DO-IT Pals programs, their email addresses are added to appropriate distribution lists according to their program memberships and disabilities.

Provide Guidance to Parents.

Help parents understand both the benefits and risks of Internet access for their children. Encourage parents of participants to put their Internet-connected computers in high-traffic areas of their homes. If an Internet-connected computer is in the family room or other busy area, children will be less likely to engage in inappropriate activities. They should avoid having a computer with an Internet connection in a child's bedroom; this might be a better place for a computer with educational software, applications software, and games that do not require the Internet.

Encourage parents and guardians to talk to their children about both the benefits and the dangers of the Internet. They should describe scenarios in which a child could be exposed to inappropriate resources or communications. These conversations should be periodic and along the same lines as those about where it is safe for children to ride their bicycles and what to do if a friend wants to play with his dad's gun. They need to be clear about what activities their children are allowed to engage in, what types of Internet resources are and are not appropriate for them, and what they are to do if they encounter materials that they feel uncomfortable with or that they know are unacceptable to their parents. Children should also know what they should do if a friend exposes them to Internet use they know is wrong.

Parents and guardians should tell their children not to give out identifying information (for example, their last name, home address, phone number, or school name) in a chat room, on an email discussion list, or in a message to an individual that they and their children do not both know and trust. Children should never respond to messages that are harassing, threatening, of a sexual nature, or obscene or that make them feel uncomfortable in any way. Protégés should know that mentors may be valuable resources to them but that they need to take responsibility for participating only in conversations and activities that are appropriate and report concerns to parents and the e-mentoring community administrator.

Parents and guardians should be sure their children know to never arrange a face-to-face meeting with people they meet on the Internet, even if they are mentors or other program participants, without parental permission. If a parent approves of a meeting between his or her child and a person met on the Internet, they should accompany the child and arrange to meet in a public place.

Consider supporting an e-community for parents of participants. In DO-IT, we created a discussion list, doitparent@u.washington.edu to facilitate ongoing communication between DO-IT Scholar parents and DO-IT staff.

Establish a system whereby new mentors and protégés are introduced to community members.

The electronic community administrator can send messages to introduce new mentors or protégés to the group and invite new members to send messages about themselves to the group. For example, the administrator of the DO-IT online community might send the following message when a new DO-IT Mentor, Jane Smith, joins the program.

To: doitchat@u.washington.edu

Subject: Please welcome a new mentor

Hello everyone,

I would like all of you to please help me welcome Jane Smith to the DO-IT community. Jane is a new mentor who works for a local computer manufacturing plant. Please take a moment to send an email to Jane and introduce yourself. You can reach her directly at janesmith@mentor.com.

Welcome to the DO-IT community, Jane!

[name]

E-Mentoring Administrator

DO-IT also publishes DO-IT Snapshots and distributes it to all e-community members. This publication includes current bios and email addresses of participants. A version without email addresses can be found online on the DO-IT Snapshots page.

Provide Ongoing Supervision of and Support to Mentors.

Addressing the needs of mentors is key to a successful mentoring community. Most mentors experience some frustration and confusion regarding their roles, especially early on. Access to administrative staff and other mentors can help them get past the rough spots as well as provide ongoing guidance. The mentoring community administrator can model how discussion questions can be submitted to a group. When mentors send good questions to the list, the administrator can send an appreciative email to their individual email addresses.

Administrative staff should have regular communication with each mentor to address questions and identify challenges and solutions. These interactions help mentors feel appreciated, maintain a positive attitude, and maximize success in their mentoring roles. The mentoring community administrator should privately encourage individual mentors, near-peers, and protégés to participate when they have not done so in a while.

A discussion list or other electronic forum just for mentors can be used by mentors to support one another. In addition, the electronic community administrator can support the mentors by sending specific resources and guidance to this discussion list periodically, as is done with the messages labeled Mentor Tip in future chapters of this book. For additional ideas regarding the support of mentors, consult the publication Supporting Mentors at www.ppv.org/ppv/publications/assets/31_publication.pdf.

Monitor and manage online discussions.

In a perfect world you could create an electronic distribution list or a web-based forum for protégés and mentors with guidelines for their interactions, and they would automatically communicate with one another appropriately and regularly. This is the essence of how a topical listserv/listproc discussion list typically works. However, in a mentoring community you have more specific goals for the participants than simply to discuss a common interest. Someone needs to be assigned the tasks of monitoring and managing the discussions of the mentoring community and sending discussion questions when needed to promote interactions. There are no formal rules to employ, but the person with that assignment can benefit from using the content in future chapters of this book as a guide.

After providing general guidelines and training to new mentors, introducing them, and encouraging them to send messages introducing themselves, the mentoring community administrator can send one short, engaging message on one topic at a time and allow time for discussion before sending out a message on another topic. The administrator can then monitor conversations and assure a natural flow of communication. Some messages are best sent by a specific mentor or protégé. In this case, the administrator can ask a specific participant to send the message to the group. This approach assures that discussions are dominated by mentors and protégés, not program staff.

Protégés should be encouraged to send messages with a focused subject line and a question related to their current experiences. For example, the administrator could encourage a participant to submit the following question to the group: "I'm applying for a summer job and need to send a résumé and cover letter. I expect I will need disability-related accommodations to succeed in the position available. Should I inform the potential employer of my disability now, wait until I get invited for an interview, or wait until I am offered the job?"

Developing good questions to discuss is essential. This book gives you some great examples, but you will want to develop your own and have your participants do the same. Program staff should view their role as community facilitators, not the central focus. To support a discussion, administrators can do the following:

- Use questions that are short, focused, open-ended, and of interest to most participants and that solicit a variety of opinions rather than one right answer.

- Rephrase or provide an example related to a question if participants seem confused.

- Use subject lines that specify the focus of the discussion, for example, "Disclosing a disability in employment?"Avoid vague subject titles like "Question from a mentor."

- Submit comments to keep a conversation going, but back off when participants are keeping the discussion lively by themselves.

- In private email messages, encourage mentors and protégés to submit questions to the group.

- Promote communications from participants. For example, after someone's contribution you might send a message such as one of the following: "What a great story, John. What did you learn from this experience?" "Sherry, could you share with the group more about how you applied for this scholarship?" "Tell us about what accommodations you're using on your new job." "How did the reaction of that teacher make you feel?" "If you had this to do again, would you take the same action?"

- Whenever possible, let the participants resolve their own disputes, and reprimand privately those who send inappropriate messages. Rarely is it necessary to send such a message to the whole group.

Share resources

The e-mentoring community administrator or another staff member should search the Internet for useful resources and provide regular messages that point to these resources. There is no guarantee that individuals will make use of content in these electronic lessons, but participants are likely to make use of at least some of the content if it is tailored to the interests of the audience.

DO-IT staff search for and distribute to appropriate lists useful resources on college and career preparation, scholarships, internships, and other appropriate topics for the community. DO-IT has also developed a standard format for lessons to support its academic and career goals for young people in the program. One lesson is sent to the mentoring community each Friday with a standard subject line of "DO-IT Lesson: [lesson title]." For samples of these messages, consult DO-IT Internet Lessons. Permission is granted to distribute the lessons provided at this site to your participants provided the source is acknowledged. These lessons complement the interactive activities included in future chapters of this book.

Employ strategies that promote personal development.

Coordinating mentor-, near-peer-, and protégé-initiated discussions and sending out periodic lessons with useful resources are important activities for supporting an electronic community. Many other mentoring strategies can be modified for online delivery to support young people on their journeys toward successful, self-determined lives. The types of online activities for teens included in this book apply recognized strategies for self-development. Among these are role modeling, affirmations, self-assessment, self-reflection, and visualization.

Publicly share the value and content of communications in the e-mentoring community and the contributions of the mentors.

In DO-IT, we anonymously share content in discussions within the mentoring community in a column called The Thread, which regularly appears in the publication DO-IT News. We also publish Scholar, Ambassador, and Mentor profiles. You can review past issues of DO-IT News online. Articles about DO-IT participants that have appeared in the press can be found on the DO-IT Press page.

Monitor the workings of the e-mentoring community as it evolves. Adjust procedures and forms accordingly.

Formally and/or informally survey the mentors and young people in the community to assess their level of satisfaction with its workings and collect their suggestions for improvement. Assess the impact of participation in the e-mentoring community on reaching their academic, career, and independent living goals. Make appropriate adjustments.

Have fun!

Communication between participants in the electronic mentoring community should be enjoyable for everyone. Sharing humor and personal stories should be encouraged.

Chapter Three

Orientation and Training for Mentors

A person's mind, once stretched by a new idea, never regains its original dimensions.

— Oliver Wendell Holmes —

The increased use of mentoring in youth programs can be, at least in part, attributed to the success of this type of intervention, particularly during the adolescent years of great change, risk, and opportunity. Research on traditional one-to-one mentoring has shown that protégés make significant gains in academic achievement and relationships with peers and parents as a result of frequent interactions with volunteer mentors who are primarily expected to provide support and friendship. Mentors help protégés solve problems they are currently facing, as well as avoid potential problems in the future.

Key to forming effective relationships within a mentoring program is the development, over time, of trust between the individuals involved, just as it is in naturally-forming mentoring relationships. Effective mentors:

- involve youth in deciding how they will spend time together

- are good listeners

- give protégés a great deal of control of topics for discussions

- are understanding and patient

- make a commitment to being dependable, maintaining a steady presence in the young people's lives

- recognize that relationships with protégés may be fairly one-sided for some time and may involve periods of unresponsiveness from the protégés

- take responsibility for keeping relationships with protégés alive

- pay attention to protégés' needs for fun and understand that enjoyable activities can provide valuable mentoring opportunities

- respect the viewpoints of youth

- point out various viewpoints regarding a situation and the people involved, propose various solutions, and facilitate discussions of alternatives

- offer expressions of confidence and encouragement even when talking about difficult situations

- find ways to show approval of young people and some of their ideas

- are sensitive to the different styles of communication of young people

- seek and utilize the help and advice of the mentoring program staff

Less effective mentors tend to:

- try to transform or reform young people by setting specific goals early on

- emphasize behavior changes more than the development of mutual trust and respect

- do not communicate with protégés on a regular basis

- demand that youth play an equal role in initiating contact

- act as authority figures or make judgmental statements about the attitudes of the young people involved

- attempt to instill a set of values that may be inconsistent with those the young people are exposed to at home

- preach to participants, telling them the one best solution to their problems

- ignore the advice of program staff about how to respond to difficulties in the mentoring relationship (Sipe, 1996)

Mentoring is a challenging job. Mentors can benefit from instruction and support in their efforts to build trust and develop positive relationships with young people.

The concept of mentoring is simple; the implementation of a mentoring program is challenging. Successful programs standardize procedures for the screening, orientation, training, and support of participants, including the mentors. Providing young people with mentors without giving sufficient direction to the mentors is unlikely to generate the long-term positive impact you desire.

Administrators of mentoring programs should consider including the following content and activities to train mentors:

- Provide information about program goals, requirements, staff roles, and other resources.

- Inform mentors of characteristics of the young people who are in the program.

- Make sure mentors understand that mentoring takes ongoing time and effort.

- Encourage mentors to ask questions of the administrator and of other mentors.

- Help mentors understand the scope and limits of their role as mentors.

- Help mentors understand that they are responsible for building relationships with participants; focus on establishing a bond with a feeling of attachment, trust, and mutual enjoyment; and that trust building is a gradual process.

- Build the confidence of mentors, and help them understand the value of their unique contribution to the lives of young people in the program.

- Inform mentors of how their support can nurture internal qualities that guide choices and create a sense of purpose. For example, Search Institute (Scales & Leffert, 1999) has identified twenty internal assets for young people as characteristics of people on the road to personal, academic, and professional success. These assets are grouped into four categories—commitment to learning, positive values, social competencies, and positive identity—that can be used in training mentors.

- Introduce mentors to general strategies for positive youth development and support. Help them focus on the overall development of young people and value the diverse backgrounds, experiences, attitudes, and abilities of participants.

- Help mentors develop the communication skills and attitudes they need to perform well in their roles.

- Prepare mentors for the frustrations they may encounter and the limitations of their impact on the young participants; help them have realistic expectations.

- Encourage mentors to find ways to have fun with their protégés as a way to help young people relate to them and feel that they value their company. Enjoyable activities include talking about interesting topics, sharing humorous experiences, pointing to interesting online resources, talking about current events and community service opportunities, sharing challenges in succeeding in college and getting a job, and talking about personal goals.

For additional guidance in this area, consult the publication Training New Mentors at www.ppv.org/ppv/publications/assets/30_publication.pdf.

Since many of the DO-IT Mentors are not local to the DO-IT Center in Seattle, orientation and training occurs online. When applicants are accepted as Mentors, they are sent a series of orientation email messages designed to introduce them to mentoring goals and strategies and to the workings of the DO-IT electronic community. We include in the training specific rules and procedures of the program; responsibilities and expectations for mentors; the background, characteristics, and needs of the young people involved; relationship skills; email communication skills; and typical challenges mentors encounter. DO-IT Mentors are encouraged to read Building Relationships: A Guide for New Mentors at www.ppv.org/ppv/publications/assets/29_publication.pdf.

As you begin to develop your own mentor orientation and training program, you may wish to use some of the following messages whose titles begin with Mentor Tip. They can be sent to an individual new mentor or to a discussion list or web-based forum for mentors to help them develop strategies for working with protégés. They are designed to provide guidelines to mentors before their full participation in the online community with protégés. Note that some of this content is published in Taking Charge: Stories of Success and Self-Determination (Burgstahler, 2006c).

Mentor Tip: Orientation

Send this message to the mentors only.

Subject: Mentoring orientation

Welcome to the [program name] program. I am the administrator of our electronic mentoring community. If you have any questions or concerns, please contact me at [email address].

To help you transition into your new mentoring position, read the publication titled Opening Doors: Mentoring on the Internet. If your computer has the capability, also view the video at the same location.

[name of e-mentoring administrator]

Mentor Tip: Discussion Lists/Forums

Send this message to the mentors only.

Subject: Mentoring discussion [lists/forums]

As a mentor you are encouraged to communicate with both mentors and teenage participants (protégés) in our mentoring community. I will post some messages to stimulate discussion, but both mentors and protégés are encouraged to share resources and pose questions of interest to the group.

The electronic community is composed of several [discussion lists/forums], each with a specific audience.

- To communicate with fellow mentors only, send a message to [list/forum address].

- To communicate with the entire community of mentors and protégés, send a message to [list/forum address].

I hope you enjoy your experience as a mentor. If you have any questions about being a mentor, how the discussion [lists/forums] work, or other issues or concerns, please contact me at [email address].

[e-mentoring administrator name]

Mentor Tip: Mentoring Guidelines

Send this message to the mentors only.

Subject: Mentoring guidelines

Here are a few guidelines to follow as you begin mentoring the teens in our program.

- Periodically introduce yourself to the group. Share your personal interests, hobbies, academic interests, and career path.

- Read messages and communicate with other mentors and/or protégés at least once per week (time commitment: up to about one hour).

- Engage protégés in conversations. Set the tone and model appropriate interactions.

- Get to know the protégés. What are their personal interests? academic interests? career interests?

- Explore interests with protégés by asking questions, promoting discussion, and pointing to Internet and other resources.

- Facilitate contact between protégés and resources (professors, professionals, service providers, etc.).

- Remember that developing meaningful relationships takes time. Give yourself and the protégés time to get to know one another.

- Encourage protégés to set and reach high goals in education and employment.

- Maintain appropriate, clear boundaries with protégés.

- Never arrange to meet a protégé in person without the approval of program staff and parents. If such a meeting is desired, please share your interest with me at [email address].

- Tell me of any inappropriate email you receive from protégés or mentors and/or inappropriate activities protégés or mentors are involved in.

Mentor Tip: Communication of Emotions

Send this message to the mentors only.

Subject: Mentoring tips on communication of emotions

There are many advantages to mentoring via the Internet. Electronic messages can eliminate the barriers imposed by time, distance, and disability that can occur in face-to-face mentoring. However, electronic messages do not include the nonverbal cues people rely upon to communicate effectively. Nonverbal cues include facial expressions, eye contact, intonation, posture, and gestures. Without these cues we can fail to properly interpret the feelings and subtle meanings behind words that are spoken. The intended message in electronic correspondence can be misinterpreted by the person reading the message.

In order to make sure the meaning behind the words in your messages is clear, consider these tips:

- Start a message with a friendly greeting ("Hello," "Hi," "Dear [name]," etc.).

- Place "(grin)" at the end of a sentence to tell recipients that your comment is meant to be humorous. Similarly, insert appropriate "emoticons" to take the place of facial expressions or gestures. You can find many collections of emoticons by searching for "emoticons" on the Web, however, it's best to use text-based content rather than graphic images so that participants who are blind can access the content with their text-to-speech systems.

- Rarely use all capital letters in a message. Capitalizing all letters in one word infers strong emphasis, but capitalizing all letters in an entire message is like yelling at someone in person.

Mentor Tip: Positive Reinforcement

Send this message to the mentors only.

Subject: Mentoring tips on positive reinforcement

Find ways to have fun with protégés and your fellow mentors. Talk about interesting topics. Share humorous experiences. Such communications help young people relate to you and feel that you value their company. Enjoyable online activities include talking about your experiences in college and employment, interesting online resources, current events and community service opportunities, and your personal goals.

Be positive and offer expressions of confidence and encouragement even when talking about difficult situations. Find ways to show approval of our young participants and their ideas and to celebrate their successes. There are many ways to do this. Here are examples of positive comments that show approval and interest.

- Great idea.

- Right on! Fantastic! Terrific!

- Great job.

- Exactly right!

- Nice going.

- Good work.

- Outstanding!

- Great! Way to go!

- Perfect.

- Excellent!

- I bet you're happy about that.

- I can tell how pleased you are about this.

- I knew you could do it.

- Wow! All your hard work paid off.

- I bet you'll celebrate this accomplishment.

- I know exactly what you mean.

- I feel the same way at times.

- Keep trying—you'll get it.

- I'd like to hear more about your thoughts on this.

- What do you recommend to other teens who wish to accomplish something like this?

- How can you build on this successful experience?

Mentor Tip: Listening Skills

Send this message to the mentors only.

Subject: Mentoring tips on listening skills

Careful "listening" is an important skill for a mentor. When you read a protégé's message, try to interpret both the meaning and the potential emotion attached to the content. Sometimes it is appropriate to let the protégé know that you are aware of strong emotions that he seems to be expressing.

Empathy lets the protégé know you not only understand the words used but also are sensitive to the feeling expressed. Statements like "You sound really discouraged" can let the protégé know that you care about more than the factual content of his message, that you care about how he feels.

When participants in our electronic community convey to one another that they hear both the content of what was said and the feelings that were expressed, close relationships with high levels of trust develop.

When communicating with protégés, it is important to

- read through a protégé's entire message carefully and ask questions about anything you don't understand, before composing your reply.

- be clear and specific in your questions, requests, and answers.

- ask open-ended questions rather than questions that can be answered with a "yes" or "no."

- understand that a protégé's view of the world may be different from your own and remember that everyone is entitled to his/her opinions and beliefs.

- provide guidance that is supportive and positive.

- avoid lecturing or passing judgment.

- guide protégés through a problem-solving process rather than state a solution to a problem for them.

Mentor Tip: Questions for Protégés

Send this message to the mentors only.

Subject: Mentoring tips on turning questions back

Sometimes an effective way to encourage communication and reflection is a question to the protégé. For example, you might ask:

- What do you think?

- Can you tell me how to do that?

- What choices do you have?

- How did you do that?

- Who helped you make that decision?

- Do you have any role models (teachers, family members, friends, historical figures, etc.) who have handled this type of situation in a positive way?

- Are you happy with how things turned out?

- What would you do differently if you were presented with the situation again?

Mentor Tip: Disabilities

Send this message to the mentors only.

Subject: Mentoring tips on disabilities

Do not ask participants about their disabilities unless they choose to disclose their specific disabilities to you. If they choose to share this information with you, encourage them to describe their disabilities in functional terms and share strategies and accommodations that help them succeed. Such practice is important since the ability for them to describe their disabilities and request accommodations is critical for their success in college and careers.

If you would like to know more about different types of disabilities and typical accommodations students with disabilities receive in educational settings, link to The Faculty Room. This extensive resource is specifically designed for postsecondary faculty and, therefore, is most relevant to the college environment. For examples of accommodations for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, link to AccessSTEM.

For further exploration of disabilities, consult the publication Disability-Related Resources on the Internet.

A glossary of disability-related terms can be found at online on the DO-IT website.

Mentor Tip: Guiding Teens

Send this message to the mentors only.

Subject: Mentoring tips on guiding teens

Reflecting on the following questions can guide you in helping young people with disabilities create definitions of success for themselves and begin to develop strategies for achieving success.

- How is your definition of success similar to or different from the definitions of young people you are mentoring? How do these differences impact your relationships?

- How do you model your own definition of success yet support a young person in defining success for himself/herself?

- What's the best advice or guidance you have ever given regarding success? What made it the best?

- Think of a time when you wished you had given different advice or guidance. What could you have said or done differently?

- How can you help teens take incremental steps toward leading a successful, self-determined life?

Mentor Tip: Conversation Starters

Send this message to the mentors only.

Subject: Mentoring tips on conversation starters

A challenge faced by any electronic mentoring community is getting conversations started. As a mentor you have the responsibility to engage protégés in conversations that promote growth and build trust. Here are a few discussion ideas to get you started.

- Introduce yourself and ask protégés about themselves.

- Talk about your hobbies, favorite movies, books, music, family, community where you live, etc.

- Ask protégés about their hobbies, favorite books, music, family, school, academic and career plans, etc.

- Talk about your education (favorite classes, teachers, school).

- Talk about your first job.

- Talk about how you secured your current job. What specialized training have you had?

- Talk about how to locate an internship or job opportunity.

- Offer to help protégés develop or improve their résumés.

- Talk about interviewing techniques, such as dressing for success, answering specific questions, and disclosing disabilities.

- Talk about disability-related accommodations in school or on the job.

- Offer to help protégés locate summer employment or make career contacts.

- Talk about balancing school, work, and social life.

- Share websites you think protégés might find useful or interesting.

Mentor Tip:"Dos" when Mentoring Teens

Send this message to the mentors only.

Subject: Tips on"dos" when mentoring teens

Since becoming self-determined is a lifelong process, you can be a co-learner as you help young people develop self-determination skills. Successful individuals with disabilities offered the following advice as part of an electronic mentoring community discussion.

- Allow them to reach for their dreams, regardless of how impossible it may seem. Encourage them when the going gets rough, let them work at it themselves to achieve their dreams, and be there to say, "Job well done!" when they make it! I thank God daily for those teachers, my family, and friends who didn't give up on me or my goals. They made my success possible!! (college student who is deaf)

- Help a disabled student accept the fact that they are disabled. Some disabled students do not want to admit their disability. Some blind students, for example, don't want to use a cane because they fear that people might look at them differently. Every child wants to be like everyone else. I remember when I was declared legally blind I didn't have the self-esteem to admit that I was blind. I didn't want to use the adaptive materials that my vision teacher provided. My grades started to slip, and I didn't feel good at all. The day that I got over the self-esteem issue was the day that I could see that adaptive materials could actually help me out in the classroom. (college student who is blind)

- Allow young people to keep their door of opportunity open, and remind them that the door will always be open as long as they allow it to be open. (college student who had a stroke)

- Caring adults can impact and shape the self-esteem of a kid, especially one who is disabled. When a kid is supported by someone outside of the their family, they feel special and valued. This"mentor" can let the child know that they believe in them. A belief is one step on the road to success. (high school student with dyslexia and attention deficit disorder)

- Give children with disabilities responsibilities at a young age, similar to those given to other children. (college student who is blind)

- Everyone should always try to reach their full potential, and they should expect nothing more and nothing less. (college student with low vision)

- If a student is having a difficult time in one academic area, gently point out to them what their strengths are, what they are better at. (college student who had a stroke)

- Instill self-confidence, self-esteem, and self-advocacy at a very young age. Allow children to learn how to be independent so that they don't have to learn how to do it when they become adults. I think when parents do everything for their children it hinders their ability to develop and be able to make their own judgments. Instill information into children that will allow them to make good judgments. (graduate student with a hearing impairment)

- Parents, teachers, and society need to come to understand that disabilities are merely factors of life, not life itself. Parents of disabled children should reinforce, from the time their children are young, that disabilities are circumventable. They must help their children accept their disabilities and then encourage them to lead their lives to the utmost normalcy. As for teachers, they must come to understand that disabled children are, in most instances, capable of achieving the same levels of academic success as any other child. Teachers must come to see disabilities as superficial qualities but simultaneously realize that disabled children may need some special accommodations. Last, society must be educated as to the capabilities of disabled individuals. While there have been vast shifts in societal thought concerning the abilities of the disabled, too many individuals still hold outdated and ignorant views about people with disabilities. It is not enough that laws exist to protect the interests of the disabled. Society must learn to take those laws to heart to ensure that all children, disabled or not, are able to form and maintain high expectations for themselves. The change will be gradual but well worth it! (adult who is blind)

- Teach your child about right and wrong. Encourage him to stand up for what is right. (college student with a mobility impairment)

- What really helps kids with disabilities is being treated just like everyone else. If they get special treatment, then they will expect to be treated like that all their lives. (high school student with speech, hearing, and mobility impairments)

Keep these words of wisdom in mind as you mentor protégés.

Mentor Tip: "Don'ts" when Mentoring Teens

Send this message to the mentors only.

Subject: Tips on "don'ts" when mentoring teens

Successful individuals with disabilities offered the following advice as part of an electronic mentoring community discussion.

- Don't disregard their beliefs or feelings. Be supportive of kids' beliefs. (college student with mobility and health impairments)

- Don't let children sit and feel sorry for themselves. Find activities of interest that they are able to take part in. Find community partners to take them places if they are unable to go on their own. (college student with cerebral palsy)

- Don't polarize disabilities and abilities. They are not two ends of a spectrum. For example, my deafness gives me access to sign language and typing skills that I might never have learned if I had not gone deaf. So in many ways the disability (if you call it that) is an ability. At the same time, my physical disability gave me an opportunity to do dance. Something I NEVER did as a nondisabled person. It's as important to identify parts of life as a disabled person that give us skills as identifying other abilities/disabilities. (adult who is deaf and has a mobility impairment)

Chapter Four

Introduction to Mentoring for Success and Self-Determination

Don't walk in front of me, I may not follow. Don't walk behind me, I may not lead.

Just walk beside me and be my friend.— Albert Camus —

A primary goal of the DO-IT electronic mentoring community is to support the participants in their transitions to successful, self-determined adult lives. In this context, being successful does not mean that you are successful in all that you do but rather that you are satisfied with your overall progress toward the goals you have established for yourself. Everyone experiences success; everyone experiences setbacks and even failure. In this chapter, mentors and protégés begin to explore the topics of success and self-determination.

The multifaceted topic of success can be approached in a variety of ways. Some professionals have looked at characteristics that successful adults have in common. For example, positive attitude has been found to be a common characteristic of successful adults. As shared by a college student who is blind: