Access to Computers

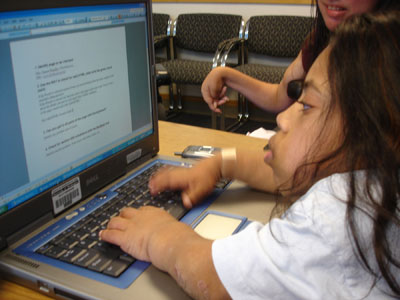

Using computing resources can increase the independence, capabilities, and productivity of students with disabilities. Computers can benefit people with low vision, blindness, hearing impairments, speech impairments, specific learning disabilities, mobility impairments, and health impairments.

Background

Access to computing resources for students with disabilities involves two issues: access to the computers themselves and access to electronic resources. Electronic resources include applications and programs (e.g., word processors and spreadsheets) and information resources (e.g., online encyclopedias and databases). In this section we will look at the solutions that adaptive technology provides in enabling access to computers for people with disabilities.

View the video and read the publication Working Together: People with Disabilities and Computer Technology for an overview of computer access challenges. The video highlights some of the special advantages access to computers, adaptive technology, software, and the Internet provide to people with specific disabilities. For more information about technology access issues in the workplace view the video Access to Technology in the Workplace: In Our Own Words.

As the individuals in the videos demonstrate, computers help reduce many barriers faced by people with disabilities. There are various technologies that make it possible for people who have disabilities to use computing resources. The videos highlight several examples, since abilities, disabilities, and learning styles are unique to each person. Many accommodations are simple, creative alternatives to traditional ways of doing things. Teachers and students can generate other effective strategies.

Access challenges and solutions for students with a variety of disabilities are described in the following sections. Disability categories covered include sensory impairments, specific learning disabilities, mobility impairments, and health impairments.

Sensory Impairments

The appearance of personal computers twenty years ago heralded new education and employment opportunities for people with disabilities, including those with sensory impairments. Because sound was rarely used, people with hearing impairments experienced few limitations in operating the early personal computers. Not long after the introduction of the personal computer, software and hardware systems for reading on-screen text aloud were developed for people with visual impairments.

As computers and operating systems have become increasingly sophisticated, adapting computers for use by people with sensory impairments has posed increasing challenges. The advent of graphical interfaces (e.g., Microsoft Windows and the Apple OS) complicates computer access for people who cannot see the screen, since their speech output systems read only text. Multimedia output that uses audio is not accessible to people who cannot hear. And people who cannot feel a keyboard cannot type effectively. Fortunately, specialized hardware and software can make computer systems usable by anyone with a sensory impairment.

Types of Sensory Impairments

A person with a sensory impairment has a reduced ability or lack of ability in using one or more of three senses—vision, touch, and hearing. The effects of a sensory impairment can range from slight to complete loss of ability to use the sense. It may have a mild or severe impact on daily living. Sensory impairments may be present along with other disabilities such as mobility impairments or learning disabilities.

Visual impairments include low vision and blindness. Low vision is used to describe a loss of visual acuity while retaining some vision. It may be combined with light sensitivity and can vary in its effect. Some people with visual impairments have uniform vision loss. Others might have visual field limitations that result in tunnel vision or alternating areas of total blindness and vision. Some people experience loss of color vision. Blindness usually refers to a complete lack of vision; however, people who are legally blind may have some useful vision.

Hearing impairments include partial or complete hearing loss. People who are deaf have very little useful hearing ability. Those who have more functional hearing ability are referred to as hard of hearing.

Nerve damage associated with diabetes may result in peripheral neuropathy. This condition is manifested in numbness or a lack of sensitivity in limbs, including fingertips.Sometimes it is obvious that a person has a sensory impairment—for example, a person who uses a guide dog. Other disabilities are less apparent. For example, someone who is deaf or who has neuropathy may have no obvious impairment. Someone with a sensory impairment may not require any special technology, while others require significant enhancements to a standard computer in order to access all features.

It is useful for assistive technology practitioners to know about specific disabilities and how they might affect successful computer use, but it is not essential to be a disability expert. It is less important to know how a sensory impairment was acquired than it is to know what abilities a person has and what tasks they need to perform.

Although the use of assistive technology does not remove a sensory impairment, it can remediate its effects so that a person is able to use a computer with full or nearly full functionality. With appropriate computing tools and well-defined strategies for their use, the person with a sensory impairment is able to demonstrate and apply his or her knowledge.

The person with a sensory impairment should play a key role in determining his or her goals and needs in selecting adaptive technology. Once basic tools and strategies are initially selected, they can be test-driven, discarded, adapted, or refined. The end user should ultimately determine what works best. The appropriateness of specific adaptive technology for a person with a sensory limitation is usually easy to determine after a brief trial period.

View the video Working Together: Computers and People with Sensory Impairments and then read the following paragraphs for descriptions of some types of computing tools that have been used effectively by individuals with sensory impairments. The handout Working Together: Computers and People with Sensory Impairments provides further details, as well as suggested products. This list is not exhaustive; people with sensory impairments and practitioners should consider other approaches as well. New hardware and software are constantly under development and promise to continually improve access options.

Visual Impairments

The most common access approach for a computer user with a visual impairment is to enlarge the display of a monitor. This accommodation can be accomplished by using screen enlargement software. Various screen enlargement packages offer a variety of features. The most popular features enlarge the display from two to sixteen times the normal view and invert or change screen colors for those who are sensitive to the usual display of black text on a white background. Some enlargers also incorporate speech output to reduce the strain associated with reading large blocks of text.

Screen enlargement technology combined with a scanner can be used to magnify printed text. Once a page is scanned with a standard desktop scanner, the results are displayed in large print on the computer screen. Dedicated devices such as closed-circuit televisions (CCTVs), also called video magnifiers, magnify printed materials, photographs, and other objects.

People who are blind access computer output with speech or Braille output systems. Speech output is the most popular form of access. Most people who are blind use a standard keyboard as an input and navigation device, since using a mouse pointer requires accurate eye-hand coordination. Screen reader software uses predefined key combinations for review and navigation of the computer screen and is usually compatible with most standard software, including word processing, web browsing, and email.

Refreshable Braille displays are devices that echo information from the screen to a panel with Braille cells. Within the cells are pins that move up or down according to the text transmitted. Braille displays can provide very effective accommodations for users who require precise navigation and editing, such as when creating computer program code that isn't conveyed easily in speech. Some displays also provide navigation and orientation information to the computer user who is blind.

For novice screen reader users who need access to the Internet, consider dedicated web-browsing software that incorporates speech or large print. These browsers ease the process of navigating complicated websites and simplify web searching and reading online. Inaccessible web design (e.g., embedding content in graphical images without providing text alternatives) presents a significant barrier to individuals who are blind and using speech or Braille output devices.

Hearing Impairments

There are few adaptations available (or necessary) for people with hearing impairments using standard computer productivity software. Sound is used little in mainstream applications such as word processing or email, and when it is used, there is often a visual alternative. Built-in operating system features found in the control panels of software applications provide visual displays for system-generated alerts.

The increasing use of streaming media is a concern for those who cannot hear. Content developers rarely include captioning in video presentations or transcribe the audio into text.

Limited Sensitivity

Loss of sensitivity in hands or fingers due to peripheral neuropathy or other causes can make it difficult or impossible to use a standard keyboard and mouse. People with this type of sensory impairment can benefit from the use of speech-input software to control a computer and enter text. Because neuropathy may be accompanied by vision loss, use of speech output may also be required. Sometimes middleware—software that serves as a go-between for two other programs—is required for screen-reading software to work with speech output software.

Specific Learning Disabilities

A specific learning disability is in most situations a hidden disability. Because there are no outward signs of a disability, such as a white cane or a wheelchair, people with a learning disability are often neglected when adaptive computer technology is considered. However, many people with learning disabilities can benefit from mainstream and specialized hardware and software to further their academic and career goals.

View the video Working Together: Computers and People with Learning Disabilities for an overview of how computers can benefit students with specific learning disabilities.

Definitions and Terminology

A specific learning disability is unique to the individual and can appear in a variety of ways. It may be difficult to diagnose, to determine impact, and to accommodate.

Generally speaking, someone may be diagnosed with a learning disability if they are of average or above-average intelligence and there is a lack of achievement at age and ability level or a large discrepancy between achievement and intellectual ability.

An untrained observer may conclude that a person with a learning disability is lazy or just not trying hard enough. They may have a difficult time understanding the large discrepancy between reading comprehension and proficiency in verbal ability. The observer sees only the input and output, not the processing of the information. Deficiencies in the processing of information make learning and expressing ideas difficult or impossible tasks. Learning disabilities usually fall within four broad categories:

- spoken language—listening and speaking

- written language—reading, writing, and spelling

- arithmetic—calculation and concepts

- reasoning—organization and integration of ideas and thoughts

A person with a learning disability may have discrepancies in one or more of these categories. The effects of a learning disability are manifested differently for different individuals and range from mild to severe. Learning disabilities may also be present along with other disabilities such as mobility or sensory impairments. Often people with AD/HD also have learning disabilities. Specific types of learning disabilities include the following:

- Dyscalculia—A person with dyscalculia has difficulty understanding and using math concepts and symbols.

- Dysgraphia—A person with dysgraphia has a difficult time with the physical task of forming letters and words using a pen and paper and has difficulty producing legible handwriting.

- Dyslexia—A person with dyslexia has difficulty recognizing and decoding written words rapidly and automatically, making it difficult to read and spell. They often have difficulty converting letters and words presented in print into the sounds and meaning of language.

- Dyspraxia—A person with dyspraxia has difficulty with the motor planning necessary to execute purposeful, voluntary movement. A person with dyspraxia of speech or verbal dyspraxia has an impairment of speech production but language comprehension is not impacted.

- Nonverbal learning disorder—A person with a nonverbal learning disorder generally has below-average motor coordination, visual-spatial organization, and social skills with verbal skills that are average or above.

- Auditory processing disorder—A person with an auditory processing disorder intermittently experiences an inability to process verbal information

Accommodations

Assistive and adaptive technologies do not cure a specific learning disability. These tools compensate rather than remedy, allowing for a demonstration of intelligence and knowledge. Adaptive technology for the person with a learning disability is a made-to-fit implementation. Trial and error may be required to find a set of appropriate tools and techniques for a specific individual. Ideally, the person plays a key role in selecting the technology, determining what works and what does not. Once basic tools and strategies are selected, they can be test driven, discarded, adapted, or refined.

Following are descriptions of some computing tools that have been used effectively by individuals with specific learning disabilities. Further details, including product and company names, can be found in the handout Working Together: Computers and People with Learning Disabilities. This list is not exhaustive and should not limit the person with a learning disability or the adaptive technology practitioner from trying something new. Today's experimental tinkering could lead to tomorrow's commonly used tool.

Word Processors

Computer-based accommodations for dyslexia may not require specialized hardware or software. For example, a person with dyslexia can benefit from using built-in word processor features such as spelling checking, grammar checking, and adjustments to font size and color.

The use of spelling checkers can allow the person with learning difficulties to remain focused on the task of communication, rather than getting bogged down in the process of trying unsuccessfully to identify and correct spelling errors. Many word processing programs also include tools for outlining thoughts and providing alternative visual formats that may compensate for difficulty in organizing words and ideas. Additionally, color-coded text options and outline capabilities present in many word processing programs are useful tools for those with difficulty sorting and sequencing thoughts and ideas.

A word processor can also be used as a compensatory tool for a person with dysgraphia. Simply using a keyboard may be a viable alternative for an individual who has difficulty expressing his thoughts in longhand.

Reading Systems

An individual who can take in information by listening much better than by reading may benefit from using a reading system. These systems allow text on screen (document, web page, or email) to be read aloud through the computer's sound card. A scanner and optical character recognition (OCR) software add the feature of reading printed text. Hard-copy text is placed on the scanner and converted into a digital image. This image is then converted to a text file, making the characters recognizable by the computer. The computer can then read the words back with a speech synthesizer and simultaneously present the words on screen.

Reading systems include options such as highlighting a word, sentence, or paragraph in a contrasting color. The reader may elect to have only one word at a time appear on the screen to improve his or her grasp of the material. Increasing the size of the text displayed on the screen can increase reading comprehension for some people with specific learning disabilities. Changing the text or background color can also benefit some people.

Concept Mapping

Some individuals have difficulty organizing and integrating thoughts and ideas while writing. Concept mapping software allows for visual representation of ideas and concepts. These representations are presented in a physical manner and can be connected with arrows to show the relationship between ideas. These graphically represented ideas can be linked, rearranged, color-coded, and matched with a variety of icons to suit the need of the user. Concept mapping software can be used as a structure for starting and organizing such diverse writing projects as poetry, term papers, resumes, schedules, or computer programs.

Word Prediction

Spelling words correctly while typing can be a challenge for some people with dyslexia. Word prediction programs prompt the user with a list of most likely word choices based on what has been typed so far. Rather than experiencing the frustration of not remembering the spelling of a word, the user can refer to the predictive list, choose the desired word, and continue with the expression of thoughts and ideas.

Phonetic Spelling

People with dyslexia often spell phonetically, making use of word prediction or spelling checker software less useful. Software that renders phonetic spelling into correctly spelled words may be a useful tool.

Speech Recognition

Speech recognition products provide appropriate tools for individuals with a wide range of learning disabilities. Speech recognition software converts the spoken word into a machine-readable format. The user speaks into a microphone, either with pauses between words (discrete speech) or in a normal talking manner (continuous speech). The discrete product, although slower, is often the better choice for those with a learning disability, because errors can be identified as they occur. Speech recognition technology requires that the user has moderately good reading comprehension to correct the program's text output.

Organizational Software/Smart Phones

Organizing schedules and information is difficult for some people with dyslexia or a nonverbal learning disorder. They may find smart phones or other organizational software helpful because they provide centralized and portable means of organizing schedules and information. These tools can assist in keeping on task and may help provide visual alternatives to represent what work needs to be done and what has been accomplished. However, they may also put some students learners at a disadvantage by requiring yet another program and interface to learn and remember to use. Some individuals lack the attention skills to regularly check the device.

Talking Calculators

A talking calculator is an appropriate tool for a person with dyscalculia. The synthesized voice output of a talking calculator provides feedback that helps the user identify any input errors. Additionally, hearing the calculated answer can provide a check against the transposition of numbers common in reading by people with dyslexia or dyscalculia.

Low-Tech Tools

Not all assistive technology for people with learning disabilities is computer-based. Common office supplies such as sticky notes and highlighter pens provide simple means of sorting and prioritizing thoughts, ideas, and concepts. Often tools of one's own making are the most effective and comfortable accommodations for learning difficulties.

Mobility Impairments

Just as an elevator or ramp provides access to spaces when a staircase is insurmountable for someone who uses a wheelchair, specialized hardware and software, called assistive or adaptive technology, make it possible for people with mobility impairments to use computers. These tools allow a person with limited, uncontrollable, or no hand or arm movement to successfully perform in school and job settings. Adaptive technology can allow a person with a mobility impairment to use all of the capabilities of a computer.

While some mobility impairments are obvious to the observer, others are less apparent. For example, individuals with repetitive stress injuries (RSI) may have no visible impairments yet require adaptive technology in order to use a computer without experiencing pain. However, people who use wheelchairs or crutches may require no special technology to access a computer. Although it may be helpful for adaptive technology practitioners to know details about specific disabilities such as muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, or RSI, it is not essential to be an expert on these conditions. People with the same medical condition, such as muscular dystrophy, may require different adaptive technology. On the other hand, an accommodation for someone with cerebral palsy may also be used by someone with RSI. Learning, sensory, and other disabilities may coexist with a mobility impairment and can create additional computer access challenges.

Although it is helpful to recognize the specific limitations of an individual, it is more important to focus on the task to be completed and how the person's abilities, perhaps assisted with technology, can be used to accomplish the goal or task. Trial and error may be required to find a set of uniquely appropriate tools and techniques. Once basic tools and strategies are identified, the end user should test-drive the technology and choose what works best. View the video Working Together: Computers and People with Mobility Impairments for an overview of how computer access can be accomplished for students with mobility impairments.

Accommodations

In the following sections are descriptions of several strategies and computing tools that have been effectively used by individuals with mobility impairments. Further details, including product and company names, can be found in the handout Working Together: Computers and People with Mobility Impairments. This list is not exhaustive; the person with a mobility impairment or the adaptive technology practitioner are encouraged to try other approaches.

Facility Access

Before a person can use a computer, they need to get within effective proximity of the workstation. Aisles, doorways, and building entrances must be wheelchair-accessible. Other resources, such as telephones, restrooms, and reference areas, should be accessible as well. Don't overlook a simple barrier such as a single step or a narrow doorway. Work with architectural accessibility experts to ensure physical accessibility.

Furniture

Proper seating and positioning are important for anyone using a computer, perhaps even more so for a person with a mobility impairment. Specialized computer technology is of little value if a person cannot physically activate these devices because of inappropriate positioning. A person for whom this is an issue should consult a specialist in seating and positioning—such as an occupational therapist—to ensure that correct posture and successful control of devices can be achieved and maintained.

Flexibility in the positioning of keyboards, computer screens, and table height is important. As is true for any large group, people with mobility impairments come in all shapes and sizes. It is important that keyboards be positioned at a comfortable height and monitors be positioned for easy viewing. An adjustable table can be moved higher or lower, either manually or with a power unit, to put the monitor at the proper height. Adjustable trays can move keyboards up and down and tilt them for maximum typing efficiency. Be sure to consider simple solutions to furniture access. For example, wood blocks can raise the height of a table, and a cardboard box can be used to raise the height of a keyboard on a table.

Keyboard Access

The keyboard can be the biggest obstacle to computing for a person with a mobility impairment. Fortunately, those who lack the dexterity or range of motion necessary to operate a standard keyboard have a wide range of options from which to choose. Pointers can be held in the mouth or mounted on a hat or headgear and used to press keys on a standard keyboard. Repositioning the keyboard on the floor can allow someone to use his or her feet for typing.

Before purchasing a complex keyboard option, evaluate the accessibility features that are built into current popular operating systems. For instance, the accessibility options control panel in Microsoft Windows contains a variety of settings that can make a standard keyboard easier to use. For a person who has a single point of entry (a single finger or mouth-stick), use of StickyKeys allows keystrokes that are usually entered simultaneously to be entered sequentially. FilterKeys can eliminate repeated keystrokes for a person who tends to keep a key pressed down too long. Check the settings for these features and experiment with different time delays for optimum effect. The Apple operating systems have similar features.

Consider using the features common in popular word processors to ease text entry. For example, the AutoCorrect feature of Microsoft Word allows sentences or blocks of text, such as an address, to be represented by unique and brief letter sequences. Entering "myaddr" could be set to automatically display one's address in proper format. Long words can be abbreviated and entered into the AutoCorrect settings to increase typing speed and accuracy.

A keyguard is a plastic or metal shield that fits over a standard keyboard. Holes are drilled into the guard to help an individual with poor dexterity or hand control press only the desired key without inadvertently pressing other keys.

Alternative keyboards can be considered for a person who cannot effectively operate a regular keyboard despite changing settings or use of a keyguard. For people who have limited range of motion, a mini-keyboard may be considered. If a person has good range of motion and poor dexterity, a keyboard with extra-large keys (e.g., IntelliKeys) can offer a good solution. Several vendors offer an array of alternative keyboards, including those that are configured to relieve the effects of RSI.

When physically activating a keyboard by either changing the operating system settings or switching to an alternative keyboard is not possible, evaluate the utility of a virtual keyboard. A virtual keyboard appears on the computer screen as a picture of a keyboard. A mouse, trackball, or alternative pointing system activates the keys on the screen and inserts the appropriate keystrokes into the desired program. A person can enter text by clicking on specific keys on the keyboard image. Modifier keys, such as CONTROL and ALT, can also be accessed, as can the function keys. Some virtual keyboards incorporate word prediction (see below) to increase entry speed and may include alternate layouts in addition to the traditional QWERTY layout found on standard keyboards.

Word Prediction

Typing words correctly and quickly can be a challenge for some people with mobility impairments. Word prediction programs prompt the user with a list of likely word choices based on words previously typed. Word prediction is often used with a virtual keyboard to increase accuracy and typing speed. For those who type much faster than 13–15 words per minute, use of word prediction can actually decrease typing speed because of the time it takes the user to select a word.

Alternative Pointing Systems

With graphically oriented operating systems, it is vital to have access to a mouse or an alternative pointing device. For those who lack the dexterity or coordination to use a standard mouse, there are many alternatives to consider. Trackballs are a good first choice; the control surface can be easier to manipulate, and the buttons can be activated without affecting the pointer position. Some trackballs offer additional buttons that add functionality, such as double clicking, click and hold, and other commands, and can be programmed to a person's specific needs. A simple accommodation for use of a pointer by someone who can't use her hands but can move her feet is to place a standard mouse or trackball on the floor.

Other alternative pointers can be found in many mainstream computer stores and supply catalogs. External touchpads, similar to those built into many laptops, offer ideal pointing systems for some. A handheld pointing device with a small control surface area may be useful for someone with very limited hand mobility.

A person with good head control who cannot operate a mouse or alternative pointing device with any limb should consider using a head-controlled pointing system. These pointing systems use infrared detection and a transmitter or reflector that is worn on the user's head and translates head movements into mouse pointer movement on the computer screen. Use of an additional switch (see below) replaces the mouse button. Combining a head-controlled pointing system with an on-screen keyboard allows full computer control for someone who cannot use a standard keyboard and mouse.

Switch Keyboard and Mouse Access Using Scanning or Morse Code

When a person cannot use a standard keyboard or mouse, using a switch may be a possibility. Switches come in a nearly limitless array and can be controlled with nearly any body part. Switches can be activated with a kick, a swipe of the hand, sip and puff by mouth, head movement, an eyeblink, or touch. Even physical closeness can activate a proximity switch. These switches work in concert with a box or emulator that sends commands from the keyboard or mouse to the computer. Although switch input may be slow, it allows for independent computer use for some people who could not otherwise access a computer.

There are a variety of input methods that rely on switches. Scanning and Morse code are two of the most popular. Upon activation of a switch, scanning will bring up a main menu of options on the screen.

Additional switch activations allow a drilling down of menu items to the desired keystroke, mouse, or menu action. Morse code is a more direct method of control than scanning and with practice can be a very efficient input method. Most learners quickly adapt to using Morse code and can achieve high entry speeds.

Switch systems should be mounted with the assistance of a knowledgeable professional, such as an occupational therapist. It is important that switch mounting on a wheelchair does not interfere with wheelchair controls. Seating and positioning specialists can also help determine optimum placement for switches, reduce the time required for discovering the best switch system, and maximize positive outcomes.

Speech Recognition

Speech recognition products provide an input tool for individuals with a wide range of disabilities. Speech recognition software converts words spoken into a microphone into machine-readable format. The user speaks into the microphone either with pauses between words (discrete speech) or in a normal talking manner (continuous speech). The discrete speech system, although slower, allows the user to identify errors as they occur. In continuous speech systems, corrections are made after the fact. Speech recognition technology requires that the user have moderately good reading comprehension in order to correct the program's text output. Voice and breath stamina should also be a consideration when speech recognition is evaluated as an input option.

Reading Systems

An individual who has a difficult time holding printed material or turning pages may benefit from a reading system. These systems are typically made up of hardware (scanner, computer, monitor, and sound card), optical character recognition (OCR) software, and a reading program. Hard-copy text is placed on the scanner, where it is converted into a digital image. The image is then converted to a text file, making the characters recognizable by the computer. The computer can then read the words back with a speech synthesizer and simultaneously present the words on screen. Use of such a system may require assistance, since a disability that limits manipulation of a book may also preclude independent use of a scanner.

Low-Tech Tools

Not all assistive technology for people with mobility impairments is computer-based. The use of common items, such as adhesive velcro to mount switches or power controls, can provide simple solutions to computer access barriers. Often, tools of one's own making provide the most effective and comfortable accommodations for mobility impairments.

Health Impairments

Some health conditions and medications affect memory or energy levels. Additionally, some students who have health impairments may not be able to visit the lab facility because of conditions that limit their exposure to traditional forms of instruction. Providing class information or course content online and facilitating email correspondence can benefit students who access the Internet from their homes or the hospital.

Tip: Access to Computers

In the Presentations section of this notebook, you will find guidelines and materials for delivering a presentation on access to computers.

Planning for Assistive Technology

Computer and network technologies can play a key role in increasing the independence, productivity, and participation of students with disabilities in academic programs and careers. Adaptive technology comes in many forms with many different characteristics. It comes as hardware, software, or a combination of the two. Some is easy to install, and some requires long-range planning, analysis of needs and options, and funding for implementation. For example, a trackball is inexpensive and can be easily added to a workstation for assisting people who have difficulty using a standard mouse. On the other hand, text-to-speech software combined with a speaker, a scanner, Braille translation software, and a Braille printer require a significant financial investment, technical expertise, and long-term planning. Adaptive software solutions, such as screen enlargement programs, can be installed on one machine or networked so that they are available from more than one computer workstation.

Adaptive technology can be easy to use or difficult to learn, requiring a great deal of commitment on the part of the individual user. For example, an expanded keyboard plugs into a standard keyboard holder on the computer and operates like a regular keyboard, whereas a speech input system requires training to use: each user must train the system to recognize his or her voice.

Adaptive technology can be generic or unique to the individual. For example, screen enlargement software serves people with a variety of levels of visual and learning impairments; a head-controlled system is more specialized.

Given these characteristics of adaptive technology, educators should consider multiple approaches to providing accessible technology. For example, at a workstation in a computer lab, it is desirable to provide options that address the needs of a variety of students. It is best if students who use assistive technology can work side by side with their nondisabled peers. There should also be procedures in place to deal in a timely manner with specific needs that these general solutions cannot address. Lab staff can start small and add to their collection of adaptive technology as they receive requests and as they gain skills in providing training and services for them. Some of the adaptive technology they might want to purchase initially includes the following.

- Having at least one adjustable table for each type of electronic resource provides access to students who use wheelchairs or are short in stature.

- Large-print key labels assist students with low vision.

- Software to enlarge screen images provides access for students with low vision and learning disabilities.

- Large monitors of at least seventeen inches assist students with low vision and learning disabilities.

- A speech output system can be used by students with low vision, blindness, and learning disabilities.

- Trackballs provide an alternative for those who have difficulty controlling a mouse.

- Wrist and forearm rests assist many students.