Mentors Matter: Youth with Disabilities and the Pursuit of STEM

By Scott Bellman, AccessSTEM Careers, University of Washington

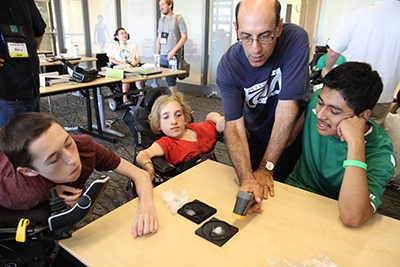

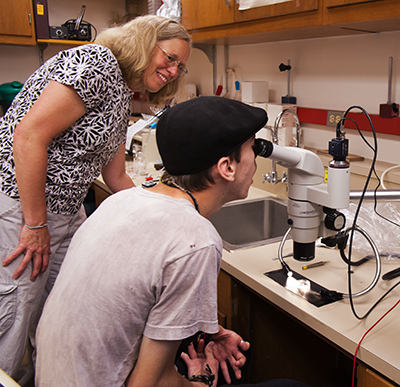

For over twenty years, staff of the University of Washington’s Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology (DO-IT) Center have worked to promote challenging academic programs and careers—especially in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), to youth with disabilities. DO-ITs AccessSTEM Careers project, funded by the Mitsubishi Electric America Foundation [www.meaf.org], provides mentors to students and recent college graduates with disabilities pursuing STEM fields. Mentoring activities occur online and in-person in the greater Seattle area.

AccessSTEM Careers mentors team up for panel presentations on the University of Washington campus, where they speak to high school and college students with disabilities about getting ready for STEM careers. Panelists, who have a variety of disabilities, work in fields such as computer programming, microbiology research, assistive technology, IT management, academic research, and engineering.

At a recent event, AccessSTEM Careers mentors spoke to a group of over 100 students with disabilities about the intersection of disabilities and the pursuit of STEM. Some of the conversation is shared here, along with resources, to empower those who would like to implement similar programs.

MODERATOR: I would like to invite the panelists to introduce themselves.

BEN: My name is Ben. I work at Boeing, where there are a lot of people who have disabilities and we have a large Deaf community as well. I have a learning disability. I worked my way through school until I got my master's degree in education from Western Washington University. I think, basically, I'm a product of hard work and a whole lot of people who helped me. I didn't get here all by myself. I think that’s important.

HADI: I'm a little older, so I need a longer introduction. (Laughter) My name is Hadi, and I'm originally from Iran. I left that country many years ago before many of you were born and went to Germany. At that time I was still sighted. I lost my eyesight over time. Ben mentioned this, and it is true for me also- when I was losing my sight, many people helped me through that process back in Germany. With support from others, I studied computer science with network management as a focus. Now my job here at the University is to work with the campus community to create more accessible applications and programs. I have experienced being a person with disability as a student, as a faculty, as a software engineer… so I think although it’s a difficult journey, it is doable if you work hard. The choice is yours.

MATT: I'm Matt. I'm a computer engineer and I write programs. Reading and writing was difficult for me because I have dyslexia. However, computers I could talk to, and they would understand me, so I got into computers. I come from a time when in school I had to type on a typewriter, which is not fun with dyslexia because I make mistakes all the time. Back when I was a student, I came to the DO-IT program and saw the diversity of the students and what they had to deal with. I met students who couldn't read or couldn't sit up or had a hard time getting around, but they were trying hard and succeeding. Looking at the amount of effort they put in really inspired me to put in more effort. I work a lot harder now. I manage software developers.

DAVID: Hi. My name is David. My degree is in microbiology. I have a minor in computer science and chemistry. I have dyslexia, dysgraphia, and ADD, which made certain aspects of high school and college extremely challenging. I'm currently employed in pharmaceutical research. I help make sure new drugs are safe before they go out in the world. When I was a student, mentors really gave me that idea that, you know, even though I had different challenges than everybody else, that I could do whatever I wanted to. In fact, within the last five years I'm actually taking up writing, which is something that most people who knew me in high school and college would not think I would do, but with the right technology, anyone can be a writer.

KELSEY: I’m Kelsey. I just finished my Ph.D. I got my degree in molecular biology on the East Coast. In terms of disability experiences, I have a neurological disability that messes with how my body functions normally and maintaining sort of homeostasis, which is very annoying. I have some connective tissue issues that cause me to have problems with mobility. I can mostly talk a lot about working hard and what it is like to sit in a lab and deal with those sorts of things.

TED: I'm Ted. I'm a software developer at Microsoft Research, and I'm deaf. I became deaf when I was 13 and it happened literally overnight. I had the mumps, and just when I thought I was over that, the next morning I was deaf. So, more about me. I am a Star Trek fan, sort of an occupational hazard for software developers…

MATT: That's more of a relationship hazard than an occupational hazard. (laughter)

TED: …I was also a wrestler, and played other sports. I went to Washington State University for four years. I worked for seven years at one software company, then I got a job at Microsoft. I started off there working in SQL Server. That was a lot of hard work. Then I went over to work on the spell checker team in Word. If you have ever used Word and seen the color squiggle, think of me. I worked on that. I'm in research right now.

MODERATOR: Let's give a round of applause for our six panelists. (applause) Who has got a question?

MENTEE: What assistive technology do you use in your everyday life?

HADI: My smart phone is one of the primary ones. I manage a lot of calling, emailing, listening to the news, finding my way with maps, and a lot of other applications. At work I use regular desktop or laptop, Braille display, and voice output.

KELSEY: So, I run Linux as my operating system and a large part of that is because Linux is functional much more easily for me without a mouse. I have trouble using a mouse because of my hands. I have a track ball for my feet and a head tracking mouse as well. For folks in lab, a lot of assistive technologies seem to be focused towards folks who do a lot of their work on computers, but there are other assistive technologies you can make use of. So I have a pipette that my employer bought for me when I was a technician. It has got multiple different programming functions. It uses much less force in the hands.

DAVID: I use dictation software. I also use the cloud technologies a lot to store notes, to access paperwork that I use. I recently started scanning in journal articles and that way I can have the screen reader read them back to me, which works with everything but science terms. But I have not found a screen reader that doesn't butcher those.

MATT: You can hire me. I'll be your screen reader. But I'll probably butcher them just as much. (Laughter)

MENTEE: I have a question for Ted. What was it like going from not having a disability to having a disability so quickly?

TED: It wasn't fun. I can tell you that. (pause) Let's see if I can remember. It was a while ago. Well, I went from being able to understand what everybody was saying and knowing what was going on, to basically feeling very alone in a crowd. It was very difficult. But I had some friends who learned sign language and that helped. I had interpreters for classes. I have interpreters now at work, too. One thing that kids have today that we didn't have back in the old days is texting. That was huge. I mean, back then if I wanted to call a girl, I had to have my friend help me call the girl. And if he thought she sounded nice, he’d say "she's not home” so he could talk to her! (laughter) At least we joked about that. I hope he was just joking. Anyway, I was very dependent on my friends to help me with that. I was always really into reading, which has helped me all the way through. If I have something I need to learn, I grab everything I can get my hands on about the subject and read it. But back to your question, yes, it was frustrating but you have to ask yourself “What am I going to do about it?” You can get as frustrated as you want, but you have to get it out of your system and get back to work.

KELSEY: I grew up in a family where I was running around as a child and playing sports and very active. And then I started having pain and I started having health issues in college and gradually came to the realization that “Okay, yep, this is my life. This is different from the life that I thought I would have as a child, but this is my life.” The thing that actually helped me was realizing that I couldn't really treat the joint condition I have. I learned to use technology, educate others, manage my situation, and so forth. Like Ted said, “what are you going to do about it?” It is what it is, right? So reframing it as an issue of disability gave me access to a community and new outlook and new ways to deal, rather than just saying "Oh, darn."

MATT: I found out I had dyslexia in the early '80s. I was in special classes. They put me with people that had behavioral problems because they just didn't know what to do with me. People just thought I wasn't that intelligent because I had a hard time communicating and I had a hard time expressing my thoughts. I also struggled with reading. And at some point I just learned that I'm different, and that's okay, and that there's going to be challenges that people are going to see or not see. I just did a job interview where I had to take a timed written test, and in my mind it took me back to college and SATs, and I'm thinking “Oh, good Lord, I'm glad I don't have to do this anymore.” But even now I still have to work through those things and figure them out.

HADI: I can talk a little bit about my transition. Remember that I'm coming from Iran in the Middle East. Being blind was taboo for the family. So I left my country at that time and went to Germany. I learned that with assistive technology, I could study all the hard stuff like math, physics, and computer science.

MENTEE: I was wondering how the workload compared from undergraduate work to graduate work and how you transitioned into your professional life.

KELSEY: When you are in grad school, there's teaching, classes, research, writing papers, reading papers, trying to get some sleep, trying to get some exercise, and you have to balance all of these things, and you have to self-manage a lot. So for people with chronic medical conditions, people with issues with executive functioning, it can be really, really hard. I found transitioning to the world of work was almost easier, because it was more predictable and there was more structure.

BEN: In an undergraduate program, the professor will say "We need you to read these specific chapters in a book." When you get into graduate school, they don't say chapters. They say books. "By the time we meet again, we would like you to have read this book!" Now, if you have a learning disability, reading might not be one of the things you really want to do, but you figure it out.

MENTEE: I have one question that I always seem to struggle with. I have a hard time sometimes socializing and personalizing. It’s like I can't figure out what social cues people are giving. Do you have any advice?

DAVID: In my experience, that gets a little easier in college because you are interacting with people who are much more understanding of what's going on, and you tend to find people with common interests. For example, biology majors tend to associate with biology majors. But it’s hard and it takes practice. There's no easy way to get better at it.

HADI: For blind people it's also very difficult to establish communication. It can be difficult to know who is around you and hard to find a familiar person, especially in crowds. My experience is that as long as you are comfortable with who you are, and you are welcoming to people, they will accept you a lot easier.

KELSEY: One thing I would say, too, is in college, you tend to interact with the same people a lot of the time, like people you live with, for example. If you have a friend that you trust, they can describe interactions from another point of view, and that can be really helpful.

HADI: You have to be patient. You will run into some people who really do not know how to deal with people with disabilities and you have to be willing to help them to understand.

MODERATOR: Matthew, I think that was a great question. I really appreciate it. I would add that you're not alone in that struggle. I'm glad you brought it up.

MENTEE: Once you explain your disability to somebody at work, do you ever have to explain it again?

KELSEY: Like many people, my disabilities are invisible, and people sometimes ask strange questions. I have lab mates who have seen me all the way from using a cane to not using a cane, to lying down on the couch, to sitting up and standing up at work. Even people that I work with on a very close basis ask me questions every day about my disability.

DAVID: Yes, people do seem to forget even if you have explained your situation to them.

MENTEE: I'm just wondering, for anyone who has a disability that might not be as apparent, in terms of getting accommodations and things like that, where you had to fight for them because maybe the person who is in charge didn't believe you when you told them that you had a disability.

BEN: If you work for a large organization like I do, they actually have their own disability management group that works with employees. We try to make as many accommodations as we possibly can to help people retain their jobs and continue to work. And so that's an ongoing process that we do. If people disclose their disability to us, then it's much easier to help them.

DAVID: I've been fairly lucky in that I haven’t experienced a lot of horror stories at work, but if you take one thing away from this panel, remember this: on your college tour, find the Disabled Student Services office and meet with them. At some point in your college career you're going to run into a college professor who questions your legal right to accommodations, and the people at disability services are the ones that will help you get through that. They also have so many other services that you wouldn't think of.

MENTEE: How did you guys apply for jobs with your disability? And was it difficult finding a job and getting accommodations?

DAVID: When you get that phone interview or the invitation to come in for an interview, you know, let them know at that time what you need to do the interview. For example, if you use a wheelchair, you need to make sure that the room is accessible.

KELSEY: I certainly never put it on the official paperwork when I am applying. But yeah, if your disability is something that needs to be accommodated in the interview process, you should ask for accommodations then. You also have the option of not mentioning it at all if you don't need accommodations during the interview process, and you may decide to have a one on one chat with your boss after you are hired. The other thing to think about too is: do you want to work with an employer if they deny you an interview because you ask for a reasonable accommodation? Maybe you don't want to work for them anyway.

Lessons Learned

Upon reflection, the high school and college students with disabilities in the audience shared lessons learned from the participants in the panel described above. They include:

- You can’t achieve success all by yourself. It’s important to find mentors.

- Although a STEM career is a difficult journey, it’s possible if you work hard.

- It’s important to adapt and learn and try different things.

- It is important to find technology that maximizes your productivity and comfort.

- Sometimes you will be frustrated, but you have to get it out of your system and get back to work.

- Sometimes you have to rediscover yourself.

- To get better at social interactions, you have to practice a lot and ask for specific feedback from people.

- Large organizations sometimes have their own disability management team that works with employees.

- On your college visits, find the Disabled Student Services office and meet with them.

- If your disability requires a reasonable accommodation to participate in a job interview, ask for it before the interview.

Replication

DO-IT maintains replication materials for AccessSTEM Careers, which can be viewed here.

Resources

The following materials are also useful to those who wish to adapt and replicate activities of AccessSTEM Careers and other projects hosted by DO-IT.

Making Science Labs Accessible to Students with Disabilities

Working Together: Science Teachers and Students with Disabilities

Video: How Can We Include Students with Disabilities in Computing Courses?

Video: STEM and People with Disabilities

The AccessSTEM Knowledge Base is a growing collection of articles related to accessibility of technology, college, graduate school and STEM careers for individuals with disabilities. This searchable resource allows users to explore a vast array of information and resources.

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the Mitsubishi Electric America Foundation (MEAF). Any opinions, findings, and conclusion or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of MEAF.

About the Authors

Scott Bellman is Program Manager of the International DO-IT Center. Scott manages programs that seek to remove barriers in postsecondary settings, prepare youth for careers, and develop resources for a wide variety of stakeholders. Scott’s training includes a baccalaureate degree in psychology and a master’s degree in rehabilitation counseling from the University of Iowa. [swb3@uw.edu]