December 8, 1998

First complete fossil of fierce prehistoric predator found in South Africa

Paleontologists from the South African Museum and the University of Washington have discovered what appears to be the first complete fossil of a gorgonopsid, a ferocious predator with both reptilian and mammalian characteristics that became extinct 250 million years ago.

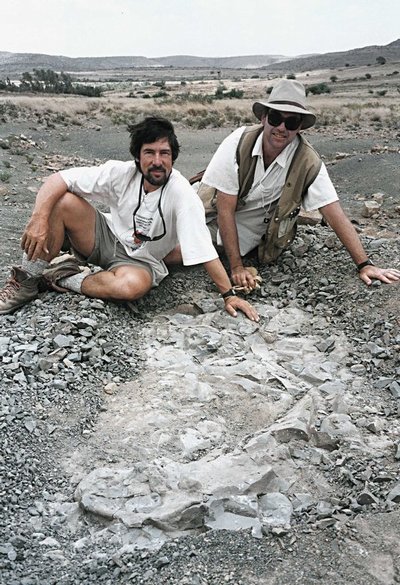

A five-person team was searching on a mile-high plateau in South Africa’s Karoo region when the discovery was made Nov. 17. Roger Smith, the museum’s curator of geology, found a small bone fragment jutting from sedimentary layer associated with the latest part of the Permian period. The layer marks the geological boundary between the Permian and Triassic periods. Smith and Peter Ward, a UW geological sciences professor, excavated the site and found a complete skeleton of a gorgonopsid – or gorgon – probably assignable to the genus Rubidgea. The skeleton was prone, head curled to the right and all four limbs tucked beneath the body. The lower parts of the skeleton, including the pelvis and lower limb bones, extended into underlying rock.

Museum scientists rate the discovery as one of the most important paleantological finds in South Africa this century. Skulls are the most common gorgon fossil discovery, Ward said. Torso bones typically have been scattered, perhaps by scavengers after the animal’s death.

The discovery is considered major because in more than 150 years of collecting in the Karoo, one of the richest fossil beds on Earth, this is the first complete gorgon skeleton found. The South African Museum’s collection of more than 12,000 skeletons from the Karoo, a desert region, includes several hundred gorgon specimens, but none approach the completeness of the latest find. Gorgon fossils also have been found in China and Russia, but none are complete, according to museum director Michael Cluver, a paleontologist.

“It’s like it just died and fell over. They never find anything like that,” Ward said.

The discovery will allow for the first time insights into the anatomy of a gorgon’s torso and limbs, and it should resolve a long debate about whether the creatures held their legs beneath them like mammals or splayed from the body like reptiles. The specimen will be given to vertebrate anatomists for study before it is prepared and mounted for display in the South African Museum in Cape Town.

Smith and Ward measured the skull at about 30 inches long, while the backbone was more than 6.5 feet long and the overall length was nearly 9.75 feet. The skeleton will be plastered and removed with jackhammers and large rock-moving equipment.

Gorgonopsids were the largest predators of the late Paleozoic, the era just before dinosaurs. They grew as large as 10 feet long and were among the most ferocious predators ever, Ward said. Their heads appeared somewhat dog-like, with large saber-tooth upper canine teeth up to 4 inches long. Though they had a somewhat mammalian appearance, their eyes were set at the sides of the head like those of a lizard, and the body was probably covered with scales rather than hair. The gorgons would have resembled a cross between a lion and a large monitor lizard – leading to the name science has given them. “Gorgons” are mythical monsters with such a horrible appearance that gazing upon them turns an observer to stone.

Gorgons are members of the Therapsida, one of the major groups of vertebrates. They shared a common descendant with reptiles, but were on a line that gave rise to mammals rather than dinosaurs, lizards, turtles or birds. They were wiped out in the world’s most severe extinction, the Permo-Triassic mass extinction of 250 million years ago that killed 80 percent to 90 percent of all species on Earth, Ward said.

The gorgon is one of 70 skeletons found by Smith and Ward on this expedition, which was paid for by the International Programs division of the National Science Foundation. The discovery came in the most recently formed rock in which such a fossil has ever been found, in sediment beds lying immediately below those marking the mass extinction. Ward said the specimen should yield valuable clues about the extinction and provide a better understanding of how the extinction took place.

“It survived until very nearly the last gasp of the Permian,” Ward said.

###

Click here for a high-resolution JPEG version of the photo.

Click here to download a high-resolution TIFF version of the photo.

Click here for a high-resolution JPEG image of a drawing by Cedric Hunter of the South African Museum of a gorgonopsid attacking a dicynodon, a tortoise-beaked herbivore. Neither creature survived the mass extinction of 250 million years ago.

Click here to download a high-resolution TIFF version of the drawing.

For more information, contact Ward after Dec. 10 by e-mail at pward@samuseum.ac.za or after Dec. 15 at (206) 543-2962 or by e-mail at argo@u.washington.edu. Smith may be reached at rsmith@samuseum.ac.za or at 011-27-21-424-3330 or 011-27-21-61-4244 (between 8 a.m. and 11 a.m. PST only). For additional comment, Ken MacLeod, a former UW research associate who worked with Ward and who will be an assistant geological sciences professor at the University of Missouri starting in January, may be reached at (206) 685-3825 or by e-mail at geosckm@showme.missouri.edu.