June 1, 2001

UW scientists say Arctic oscillation might carry evidence of global warming

For years, scientists have known that Eurasian weather turns on the whim of a climate phenomenon called the North Atlantic oscillation. But two University of Washington researchers contend that the condition is just a part of a hemisphere-wide cycle they call the Arctic oscillation, which also has far-reaching impact in North America.

Significant changes in the Arctic oscillation during the last 30 years have influenced temperature and precipitation patterns throughout the Northern Hemisphere, said John Wallace, a UW atmospheric sciences professor, and graduate student David Thompson. Those changes might well have been caused by ozone depletion over the northern polar region or a buildup of greenhouse gases, they said.

In recent years, the Arctic oscillation seems to have been stuck in its positive phase most of the time, said Wallace, who will present evidence of the phenomenon June 3 in the Charney Lecture during the American Geophysical Union‘s spring meeting in Boston.

“This Arctic oscillation seems to be doing things in the last decade or two beyond the range of what it has done earlier in the century,” he said.

In a 1995 study published in the journal Science, Wallace suggested that the global warming widely believed to be occurring could be, in part, the result of natural cycles. His work on the Arctic oscillation, paid for in part by a National Science Foundation grant, is altering his view because it includes findings that imply human-induced climate change.

“We are looking at temperature changes over Siberia in the last 30 years that are almost 10 times greater than the global mean temperature rise in the last 100 years,” he said.

In addition, significant changes in surface winds over the Arctic might have contributed to the thinning of the polar ice cap that has been reported by scientists with last year’s SHEBA (Surface Heat Budget of the Arctic Ocean) project, Wallace said.

“If it keeps going in this direction, it could be a major force for melting,” he said.

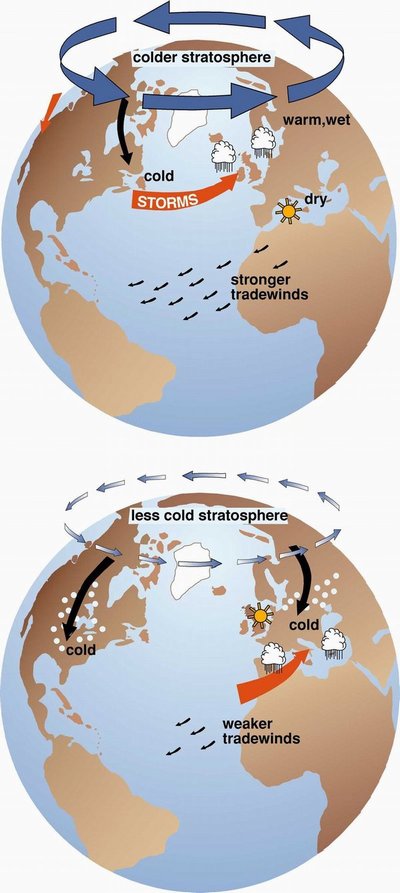

The Arctic oscillation is a pattern in which atmospheric pressure in northern latitudes switches, or oscillates randomly, between positive and negative phases. The negative phase brings high pressure over the polar region and low pressure at about 45 degrees north latitude – a line that runs through the northern third of the United States and western Europe. The positive phase reverses the conditions, steering ocean storms farther north and bringing wetter weather to Alaska, Scotland and Scandinavia and drier conditions to areas such as California and Spain.

In its positive phase, Thompson said, frigid winter air doesn’t plunge as far into the heart of North America, keeping much of the United States east of the Rocky Mountains warmer than normal. However, areas such as Greenland and Newfoundland typically are colder than usual.

One piece of the puzzle, the researchers said, is the existence of a Southern Hemisphere phenomenon, an Antarctic oscillation, which is virtually identical to its northern counterpart except that the Southern Hemisphere has a stronger vortex, or spinning ring of air, encircling the pole. That’s because, unlike in the Northern Hemisphere, there are no large mid-latitude continents like Eurasia to disrupt the circular flow, Wallace and Thompson said.

But the cooling of the stratosphere in the last few decades has caused the polar vortexes in both hemispheres to strengthen in winter. Winds at the Earth’s surface also have gained speed, sweeping larger quantities of mild ocean air across the cold northern continents. A modeling study being published in the journal Nature on Thursday by researchers at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies suggests the buildup of greenhouse gases might be contributing to colder temperatures in the polar stratosphere. If that trend continues, the colder temperatures ultimately could produce a hole in the ozone layer like that in the Southern Hemisphere, Wallace said.

The ozone layer acts as a shield against ultraviolet rays from the sun, but ozone is depleted when it interacts with chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, once common ingredients in refrigerants. International cooperation has greatly reduced the production of CFCs, but enough still linger from past decades to damage the ozone if wintertime stratospheric temperatures become cold enough to activate them.

“If the Northern Hemisphere polar stratosphere keeps getting colder, the ozone becomes more susceptible to the CFCs that are there,” Wallace said. “We may have chronic problems with ozone depletion despite curbs on CFC releases.”

###

During the AGU meeting, reporters may leave messages for Wallace at the press room, (617) 954-3094 or at his hotel, (617) 236-5800. Otherwise, contact Wallace at (206) 543-7390 or wallace@atmos.washington.edu, or Thompson at (206) 685-3775 or davet@atmos.washington.edu