January 22, 2002

Neuroscientists searching for roots of empathy find brain regions involved in learning by imitation

In a pair of pioneering studies, a French and American team of social-cognitive neuroscientists have identified a network of brain regions that are involved in human imitation and specific brain areas that enable a person to distinguish the self from others.

The research is part of a larger effort to find the neurological basis of social interaction, particularly empathy, a basic part of human nature that allows most, but not all, people to care about others.

The team is headed by neuroscientist Jean Decety of France’s Institut de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale and a visiting professor at the University of Washington’s Center for Mind, Brain & Learning, and developmental psychologist Andrew Meltzoff, co-director of the center.

“This work is important because imitation is a natural procedure. We don’t learn to imitate. It is part of our biological nature and we are born to imitate,– said Decety.

“A 3-year-old feels empathy and will pat another child on the shoulder or comfort his mom when she’s crying,– added Meltzoff. “We believe empathy has roots early in life. It may be linked to imitation, which we know babies do from a very early age.–

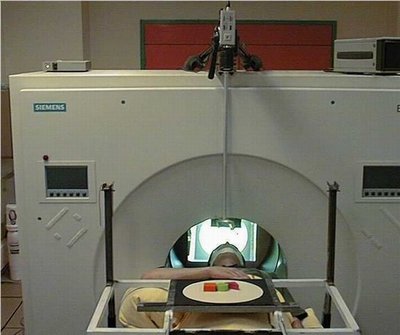

In the two studies, which are being published in the January and February issues of the journal NeuroImage, the researchers used positron emission tomography (PET) to explore the neural mechanisms of imitation by measuring increases in blood flow in the brain.

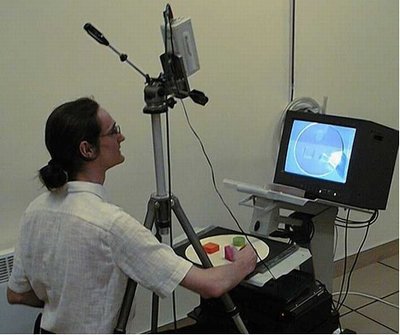

In the first study the researchers look at imitation from the point of view of a teacher (the person demonstrating a task) versus the point of view of a student (the person learning the task). Eighteen right-handed male subjects were asked to perform five tasks involving small, different colored objects. Their heads were held stationary while the PET scans made images of their brains, but they could move their right hands and watch a demonstrator’s hands reflected in a mirror.

Subjects were first asked to watch the demonstrator move the objects and then imitate the action with their hand. In the second task, they were told to move the objects first and watch the demonstrator copy them. The other three tasks were control experiments in which subjects were allowed to freely manipulate the objects any way they wanted to, just watch the demonstrator move the objects, and move the objects and then watch the other person perform different movements.

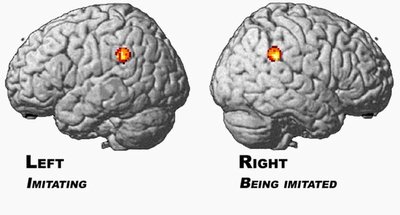

The researchers discovered a consistent pattern of increased brain activity involving the superior temporal gyrus, as well as differential activity in the two hemispheres within the inferior parietal cortex when imitation was involved. The left inferior parietal cortex showed increased activity when the subjects were imitating another person. When the subjects were being imitated by the other person, however, the right inferior parietal cortex was more activated.

Decety and Meltzoff believe the inferior parietal cortex may play a key role in whether a person attributes an action to the self or to another person.

“By imitation we may feel what another person felt, which is the very definition of human empathy,– said Decety.

“Imitation also is nature’s way of conveying culture,– said Meltzoff. “It naturally occurs in a variety of settings, such as learning to play music and sports, or when a mother teaches her daughter how to tie her shoelaces. The mother ties a shoelace and the child follows, trying to imitate the action. We would expect the same kind of lateralized brain activity in learning to tie shoelaces as there was in our experimental task.–

The second study, which involved 10 right-handed subjects, employed a physical setup that was similar to the one used in the first study. This time, however, subjects were shown video clips of another person choosing, grasping and moving a Lego block into a new position and then leaving the Lego in the new position.

In the first of six tasks, subjects had to duplicate the entire manipulation. Next they were only shown part of a video clip that showed the other person’s hand leaving the Lego in its final position and the subjects had to manipulate the block to achieve that “goal.– Subjects also viewed a clip that only showed “means,– or the manipulations of a block, and had to duplicate the movements they observed. Three control tasks also were performed. Subjects again watched the clips showing the entire manipulation, as well as just the goal and the means, and were asked to freely move their Lego in any way they choose.

This paper is unique because it is believed to be the first neuroimaging study to show that imitation can be split into two complementary components, the goal of an action and the means to achieve it.

Decety said the researchers found that not only can the components of imitation (the goal and the means) be separated, but each involves specific brain regions. Increased brain activity was detected in the medial prefrontal cortex during imitation of the means, while increased activity in the left premotor cortex was associated with imitation of the goal.

“This supports the idea that when observing someone’s action, the underlying intention is equally or perhaps more important than the surface behavior itself,– the authors write.

These findings have widespread potential applications in typical and atypical child development, educational practice and artificial intelligence.

“In child development, reading others’ goals or intentions from their actions is necessary for human interaction. If you are just literal, you will not have deep understanding of other people,– said Meltzoff. “It is also important to know what brain regions control actions and intentions. They may not develop at the same time in humans.–

“Educators sometimes pay too much attention to the means without the goal or to the goal without giving children the means, or the steps, to accomplish something,– Decety said.

The two studies were supported by funding from the French Ministry of Education and the UW’s Center for Mind Brain & Learning (CMBL). Co-authors of the papers were Thierry Chaminade and Julie Grezes, doctoral students in France.

CMBL is an interdisciplinary research center where behavioral scientists and neuroscientists are collaborating to study the links between behavior and the brain. The center is funded primarily by the Talaris Research Institute, founded by a gift from the Apex Foundation, the private family foundation created by Bruce and Jolene McCaw.

###

For more information, contact Decety at (206) 221-6473 or decety@u.washington.edu or Rose Pike at CMBL (206) 221-6473 or rosepike@u.washington.edu