May 27, 2004

UW helps students learn Arabic, set goals for future

Genevieve Shaad could be spending her Garfield High junior year taking Spanish like many of her peers. Instead, she is one of the tiny handful of high school students in America who study Arabic.

“It just seemed much more important than taking an ordinary language,” Shaad said, “because we’re over there fighting.”

With support from the UW and inspired partly by U.S. involvement in the Middle East, a nonprofit group called OneWorld Now! has been offering Arabic language classes at four Seattle high schools since September.

How unusual is that? Among America’s nearly 100,000 public schools in 1999 (the most recent year surveyed), only 15 offered Arabic.

Yet job prospects for Arabic speakers are strong, especially in humanitarian, military, academic and diplomatic fields, said Felicia Hecker, associate director of the Jackson School’s Middle East Center, which trains the OneWorld Now! teachers and provides other support.

Hecker said the need to understand the Middle East has never been more acute — and language is crucial to understanding a culture.

Or, as Garfield classmate Suzanne Hu put it: “I didn’t want to be one of those ignorant people.”

Little risk of that. Hu is one of eight from the program who will practice her new skills in Morocco this summer. The high school kids will live with host families there for three weeks while joining in public service projects with students from UW’s Comparative History of Ideas (CHID) Program.

The interaction between University scholars and high schoolers — many of whose families are low-income — is part of OneWorld Now! founder Kristin Hayden’s agenda that transcends studying an overlooked language.

“The contact with the University of Washington provides these high school kids with a long-term goal,” Hayden said. “It doesn’t do any good to give these kids amazing skills and opportunities but no long-term plan.”

Indeed, college advising and a weekly after-school leadership class are required for all 40 of the students, in addition to their twice-weekly language classes. This unique mixture of language and guidance has earned OneWorld Now! support from prestigious sources, including the Henry M. Jackson Foundation. Most recently, it received a Jack Kent Cooke Foundation grant as one of the nation’s four most innovative after-school programs.

The UW’s Middle East Center, meanwhile, supports the Morocco trip with faculty expertise and provides summer internships for the high schoolers at an Arabic-language children’s camp, said Hecker, who also serves on the OneWorld Now! board.

Return benefits to the UW, Hecker said, should include a steady stream of freshmen with a head start.

“It takes more than four years to really learn a language, especially one as difficult as Arabic,” Hecker said. “We can do so much more with students if they are coming in with some Arabic training.”

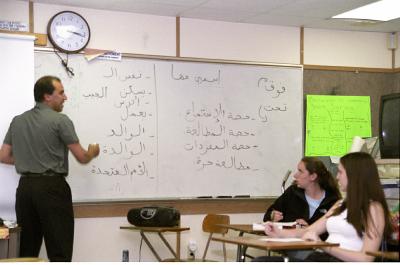

For all its national recognition, OneWorld Now! is a young start-up, just finishing its first school year of classes. The 10 Garfield students gather inside an aged-looking portable under stained ceiling tiles, where they spend two afternoons a week reciting in chorus simple Arabic phrases with their teacher, Morocco native Rachid Rhenifel.

One World Now! will send Rhenifel to the prestigious Middlebury College language teacher training institute in Vermont this summer, but he already knows how to get American teenagers to provide enthusiastic Arabic narration as he moves pens and books around a table, and counts out coins from his pocket.

The program’s goal is to expand beyond its current Seattle outposts at Garfield, Ingraham, Cleveland and Roosevelt high schools, into Portland and eventually nationwide.

There’s a large demand. University Arabic language enrollment has risen sharply since 1998, when a Modern Language Association survey found that less than 1 percent of language students took it. (The UW is considered one of the top 10 nationally in the field, offering bachelor’s and master’s studies in Near Eastern Languages and Civilization, a master’s in Middle East Studies and a doctorate in the Graduate School’s Interdisciplinary Near and Middle East Studies program).

But the UW’s first-year Arabic courses are getting increasingly crowded, Hecker said, making a high school head-start all the more advantageous.

For Hayden, OneWorld Now!’s founder, learning Russian as a kid during the Cold War was her ticket to job offers and a rewarding business career. For today’s youngsters, the ability to navigate the Middle East could prove just as useful.

“This is a skill,” she said, “that you can use for the rest of your life.”