June 3, 2004

Study: Zoning to protect forests, rural land may do reverse

More than 25 years of zoning policies intended to preserve the nature of Eastern King County’s wild and rural lands may be encouraging the very sprawl land-use planners want to avoid.

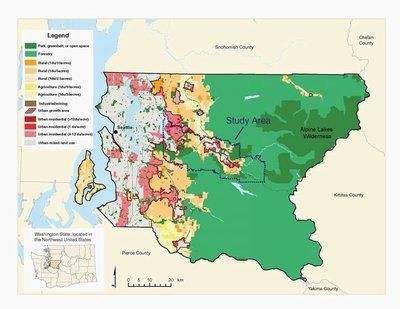

A UW study of a 180-square-mile swath of land east of Lake Sammamish shows that the low-density zoning that was intended to maintain the rural character and protect the natural environment could instead be altering forests in dramatic and unintended ways.

“It has converted, fragmented and isolated forests and rural lands,” said Lin Robinson, UW graduate student in forest resources and lead author of a paper in the journal Landscape and Urban Planning.

Nearly three-quarters of the land consumed to build single-family houses in the study area since 1974 has been in rural and forested areas governed by low-density zoning and not in more suburban areas where growth was to be concentrated. It’s the amount of land being consumed and the resulting changes in the landscape when homes are built on lots of 2.5 to 80 acres that no one has considered before, Robinson says. Most studies look only at the number of homes constructed.

The study area, which includes urban growth areas around the cities of Issaquah, North Bend and Snoqualmie, is typical of what’s considered urban fringe, an area sandwiched between a city on one side and forest and rural lands on the other.

Between 1974 and 2001, researchers found, some 4,840 homes were built outside the urban growth areas and 11,830 were built inside. The homes outside the boundaries, however, consumed more than double the acreage than those inside — 25,620 acres compared with 10,930.

Among the conversions was 17,400 acres of land classified as wildlands, which now have too many houses to still be considered as such, and 9,890 acres of agricultural lands. Meanwhile, the amount of land considered suburban increased by 12,480 acres or 765 percent.

Outside urban growth boundaries, many homes are still surrounded by forestlands but the nature of those forests can be changed, according to John Marzluff, co-author and UW professor of forest resources. It’s like taking a bite out of an apple — even a small one swiftly alters the fruit.

Widely-spaced homes, Marzluff says, can fragment the forest in ways that don’t leave room for animals that dislike being near humans such as winter wrens and Wilson’s warblers. Even a handful of homes punched into what researchers call “interior forests” — areas at least one-eighth of a mile from any road, building or cleared area — can drive away or starve out spotted owls, some amphibians and some small mammals such as the unique shrew-mole.

“If the goal is to maintain interior forests and the animals that need them, then the low-density housing formula alone isn’t working,” Robinson said of the study area, where interior habitat on wildlands decreased 41 percent since 1974.

As an additional option — it shouldn’t be all one or the other, the researchers said — policy makers might consider clustering some dwellings on smaller lots. A diversity of settlement types may allow a greater diversity of animals to survive.

The authors say King County isn’t the only entity to use low-density zoning, the well-meaning approach has been used widely by other counties and states across the nation.

Considering another prong of King County’s growth management, the authors say great foresight was shown in 1985 by forming agricultural and forest-production districts, where virtually no housing was allowed. The forest production districts in particular, along with forests preserved as wilderness, parks and federal, state and county forests, mean that more than half the county still consists of natural or second-growth forests protected from unmanaged growth.

“Given the amount of privately owned forest-production land, it is likely that some of these areas would have already been developed without these long-term designations, thereby increasing the extent of sprawl,” the authors write.

“Such landscapes are the pressure point now and for the next 50 years,” Marzluff said.

The article, “Twenty-five years of sprawl in the Seattle region: Growth Management Responses And Implications For Conservation,” is currently in press at Landscape and Urban Planning, and also includes UW geography graduate student Joshua Newell as a co-author. Funding came from the National Science Foundation and the UW.

Besides considering King County single-family building permits between the years of 1974 and 2001 — single-family homes being the largest consumers of land of any type of building — the researchers also used aerial photographs from the Washington Department of Natural Resources. Images from 1974 and 1998 (the most recent year available when the study started) were digitized and compared for changes in land-use and vegetation during a 1,000-hour effort by a five-person team of graduate and undergraduate students in the UW’s new Urban Ecology Program.