February 24, 2005

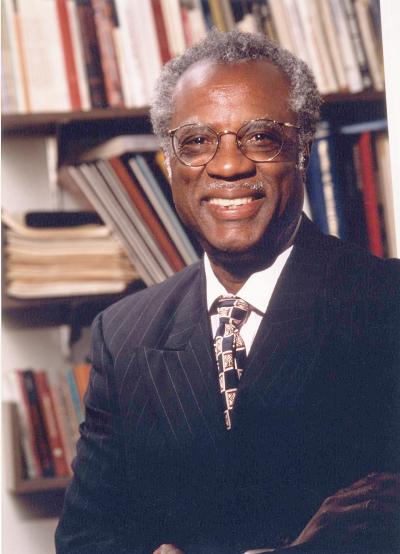

Multicultural education leader James A. Banks to give 29th Annual Faculty Lecture

As a child in the Arkansas delta in the 1940s and early 1950s, James A. Banks — who would later become an international leader in multicultural education — felt the heavy hand of racial discrimination.

As an African American, Banks was marginalized by a mainstream society badly in need of reform. He was an avid reader, but blacks were banned from the public library. He had to enter the local movie house through the “colored entrance,” which led only to the balcony, where the rattle of the projector competed with the sound of the film. Even the public drinking fountains were segregated. “We used to savor the taste of ‘white’ water when the authorities were preoccupied with more serious infractions against the racial caste system,” Banks says.

In the many years since, Banks became an elementary school teacher, then a professor, author, researcher and, in his years at the UW, a leading voice in the theory and practice of multicultural education, with some colleagues even calling him the father of that discipline.

Banks has been chosen to deliver the 2005 Annual Faculty Lecture at 7:30 p.m. Thursday, March 3, in 130 Kane, with a reception to follow in Kane’s Walker-Ames Room. His lecture will spotlight several aspects of his decades of research, writing and teaching, and is titled Democracy, Diversity and Social Justice: Education in a Global Age.

Banks’ professional activities, honors and awards fill pages. He has written or edited 20 books and more than 100 articles, has lectured and been a visiting scholar nationally and internationally. He is past president of the American Educational Research Association and the National Council for the Social Studies. He is a member of the Board of Children, Youth and Families of the National Research Council and the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Medicine. Banks also is a member of the National Academy of Education. His biography appears in several reference works, including Leaders in Education, Men of Achievement, and Who’s Who compendiums of American education, the West, America and the world.

| 29th Annual Faculty Lecture: Democracy, Diversity and Social Justice: Education in a Global Age, 7:30 p.m. Thursday, March 3, 130 Kane, free, 206-616-9733 |

Through many years and in many ways, Banks says, he has continued to pursue basic questions that struck him when he was a schoolboy in the rural South. In a 1998 paper he wrote, “One of my most powerful memories is the images of the happy and loyal slaves in my social studies textbooks … Why were the slaves pictured as happy? … Who created this image of the slaves? Why? The image of the happy slaves was inconsistent with everything I knew about the African American descendants of enslaved people in my segregated community.”

Banks said recently, “The question never ended, because it has kept taking on new forms, getting reinvented.” The childhood query, he said, has taken on the power of a metaphor for the misunderstandings and broad stereotyping that affect race relations: Why have blacks been viewed as inferior genetically? Why have they been marginalized from society and depicted as less than human?

One answer, as Banks will discuss in his lecture, lies in examining who writes the history and who constructs the knowledge that comes to be accepted as true. Banks notes one author in particular who helped to create the image of happy slaves, and postulates that the background and world views of researchers, historians and scientists can markedly affect the results of their work. He wrote, “I now believe that the biographical journeys of researchers greatly influence their values, research questions, and the knowledge they construct.”

As a leading proponent and architect of diversity in k-12 education, Banks feels strongly that the key to transcending the isolation and alienation among races is diversity, education and teacher intervention in early grades. The very nature of multicultural education, he writes, is “to Americanize America” and help it achieve its own goals of inclusion, justice and social equality. Such an approach will help close the achievement gap at home and better prepare our students for the global society. Banks will point out, however, that multicultural education is not just about ethnic minorities, but about educating all students to live in a diverse nation and world.

Banks’ lecture will focus on diversity in the world as well as within the United States. “We should educate students to be effective citizens of both the nation and the world,” he says. The goal of such a multicultural approach, Banks stresses, “is to teach students to know, to care and to act” to make their communities, the U.S. and the world more democratic and just.

Hard times at home and abroad test a nation’s values and resolve, Banks says, but he remains cognizant of how far society has come since his days on the Arkansas delta, and optimistic about the future. “It’s easy to forget the tremendous progressive forces in America and the progress our nation has made since I was a child,” he says.

“Americans have learned that out of desperation comes hope, out of oppression come possibilities.” And even in dark times, Banks says, “comes the opportunity to reaffirm our commitment to human freedom and social justice.”