March 13, 2006

Comet from coldest spot in solar system has material from hottest places

Scientists analyzing recent samples of comet dust have discovered minerals that formed near the sun or other stars. That means materials from the innermost part of the solar system could have traveled to the outer reaches, where comets formed.

“The interesting thing is we are finding these high-temperature minerals in materials from the coldest place in the solar system,” said Donald Brownlee, a University of Washington astronomer who is principal investigator, or lead scientist, for NASA’s Stardust mission.

Among the finds in material brought back by Stardust is olivine, a mineral that is the primary component of the green sand found on some Hawaiian beaches. It is among the most common minerals in the universe, but finding it in comet Wild 2 could challenge a common view of how such crystalline materials form.

Olivine is a compound of iron, magnesium and other elements, in which the iron-magnesium mixture ranges from being nearly all iron to nearly all magnesium. The Stardust sample is primarily magnesium.

Many astronomers believe olivine crystals form from glass when it is heated close to stars, Brownlee said. One puzzle is why such crystals came from Wild 2, a comet that formed beyond the orbit of Neptune when the solar system began some 4.6 billion years ago.

“It’s certain such materials never formed inside this icy, cold body,” Brownlee said.

The comet traveled the frigid environs of deep space until 1974, when a close encounter with Jupiter brought it to the inner solar system. Besides olivine, the dust from Wild 2 also contains exotic, high-temperature minerals rich in calcium, aluminum and titanium.

“I would say these materials came from the inner, warmest parts of the solar system or from hot regions around other stars,” Brownlee said.

“The issue of the origin of these crystalline silicates still must be resolved. With our advanced tools, we can examine the crystal structure, the trace element composition and the isotope composition, so I expect we will determine the origin and history of these materials that we recovered from Wild 2.”

Brownlee is among scientists presenting the first concrete findings from the Stardust sample this week at the annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in League City, Texas.

Stardust’s captured dust from comet Wild 2 in January 2004, and the sample-return capsule parachuted to the Utah desert on Jan. 15 to complete the seven-year mission. The samples from Wild 2 were taken to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, and from there they have been sent to about 150 scientists around the world, who are using a variety of techniques to determine the properties of the comet grains.

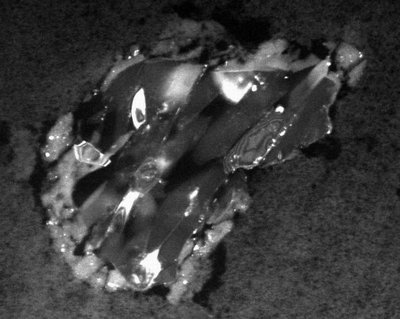

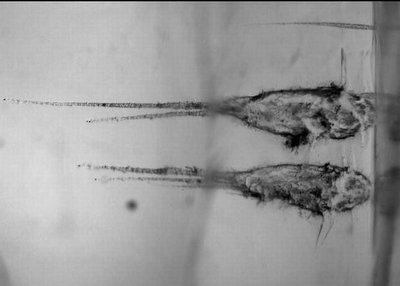

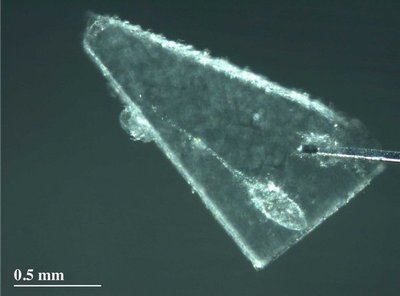

The grains are very tiny, most much smaller than a hair’s width. But there appear to be thousands of them embedded in the unique glassy substance called aerogel that was used to snare the particles propelled from the body of the comet. A grain of 10 microns — one-hundredth of a millimeter — can be sliced into hundreds of samples for scientists to study.

“It’s not much, but still it’s so much that we’re almost overwhelmed,” Brownlee said, noting that his lab has only worked on two particles so far. “The first grain we worked on, we haven’t even cut into the main part of the particle yet.”

The material, which came from the very outer edges of the solar system, has been preserved since the start of the solar system in the deep freeze of space 50 times farther away from the sun than Earth is. Brownlee believes the material will provide key information about how the solar system was formed.

“A fundamental question is how much of the comet material came from outside the solar system and how much of it came from the solar nebula, from which the planets were formed,” he said. “We should be able to answer that question eventually.”

Besides the UW, other major partners for the $212 million Stardust project are NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Lockheed Martin Space Systems, The Boeing Co., Germany’s Max-Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, NASA Ames Research Center, the University of Chicago, The Open University in England and Johnson Space Center.

###

For more information, contact Brownlee at (818) 726-5563, (206) 543-8575 or brownlee@astro.washington.edu

Stardust on the Internet, http://www.nasa.gov/stardust