April 23, 2009

Enter the world of melodrama — as it was really done — in School of Drama’s ‘The Two Orphans’

A villain with a black cape who twirls his moustache and leers at a victim tied to the railroad tracks — this is what most of us think of when someone says melodrama. But that’s just a caricature of the form, says Jeffrey Frace, who is directing the School of Drama’s production of the melodrama The Two Orphans, which opens next week.

“Melodramatic is a derogatory term these days because it’s come to us as a synonym for bad acting,” says Frace, an assistant professor at the school. “But that’s a misunderstanding that I think has come via bad imitation of an external form without really knowing where it came from.”

Where it came from is France, and its glory days were in the 19th century. The Two Orphans was written in 1874 by Frenchmen Adolphe d’Ennery and Eugene Cormon. Like all melodramas, it features fairly straightforward good and evil characters, with the good characters repeatedly getting into dangerous situations from which they must rescue themselves or be rescued.

“Melodrama exists to lead the characters to emotional crises, one after another, just so we can bring the actor downstage into the spotlight for their shining moment where they reveal who they are and what they’ve suffered,” Frace says.

Quite the anathema today, when the most admired actors disappear into their characters and achieve success through understatement. But 19th century France was a different kind of time and place. The spectators for melodramas were poor people who came to the theater to see the actors. And having come, they wanted to see those actors emote. As Frace puts it:

“The loud voices and exaggerated gestures of melodrama are there in order to reach the people sitting in the poorest seats in the highest balconies — the working people of Paris who have rubbed together their last pennies to come see their favorite actors on stage. The actors are reciprocating their love affair with the people by playing way up and out to them. Everything that we see as artificial now — the turns out, the big gestures, the loud speaking, the stomping across the stage — are all to make sure that the people way up there, who are a little tired after their day’s work, and maybe a little drunk too, are really following the story.”

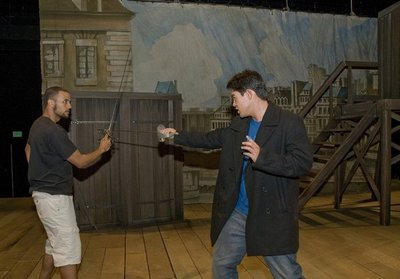

The story of The Two Orphans involves two sisters, Henriette and Louise, who travel to Paris in hopes of finding a cure for Louise’s blindness. The orphans are soon separated when Henriette is abducted by a sleazy nobleman who wants to make her his lover, and Louise is tricked by a family of beggars who promise to help her find her sister, but instead force her to sing for money on the streets. And that’s just the beginning.

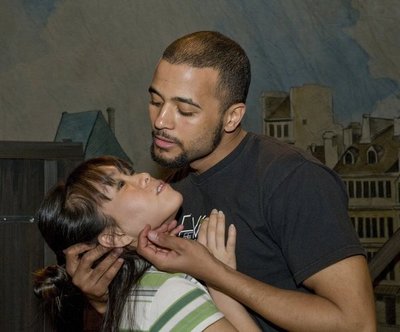

Presenting such a plot successfully requires a different style of acting than the one today’s performers are used to, Frace says. So, to prepare his actors, he offered a class in winter quarter for the first and second-year graduate students in the Professional Actor Training Program. He taught them how to enter, walk in an arc, turn out to the audience and find “fixed points” — suspended moments of stillness as they gesture.

Once in rehearsal, they had to learn how to use a series of stock gestures spelled out in a book called Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action, written by Henry Siddons and published in 1822. The book contains drawings of gestures for each emotion, many of which Frace posted in the rehearsal hall for the students.

Although it may seem silly to “strike a pose” to express an emotion, Frace says that he had “never seen actors look so beautiful” as they did when he first saw them performing in this style, during a workshop he took when he was in an MFA program at Columbia University. After he finished the program, during which he’d felt “beaten up” by a director he describes as brilliant but harsh, he sought to rediscover the joy of his profession and signed up for a workshop with French acting teacher Phillippe Gaulier, whose classes included clowning and melodrama. He found himself immediately enthralled with the style — so much so that he’s since written a musical melodrama that he’s workshopped in New York.

But it isn’t just the beauty of the gestures that has captivated Frace. He also believes that beneath the artificiality is something else.

“There’s something archetypal about [these gestures] which has become stereotype and cliche,” he says. “But I tend to think that things that have become stereotype and cliche must once have been powerful, and that’s why they were repeated and repeated and imitated so much and so badly that they eventually lost their power. I’m wondering if we can go so deeply into the stereotype of what some of these melodramatic gestures look like that we might get to something that’s more archetypal, more powerful. It’s also a great exercise for the actors because it just forces them out of their neutral, 21st century slouching body.”

Essentially, Frace says, melodrama is about acting full out, with no holding back, no worrying about whether you’re being hammy or looking foolish.

Noam Rubin, who plays Pierre, one of the heroes in The Two Orphans, says the experience has been about doing more than the actor thinks is necessary. “This doesn’t mean you have to be constantly flailing your body around the stage and mugging to the audience,” he says. “Instead, it helps to be intensely real and intensely emotional. Being sad isn’t enough. You must feel this sadness times ten in every part of your body… and you must share these emotions openly with the audience and constantly be checking in to make sure they’re with you.”

Clearly, the UW actors won’t be playing The Two Orphans for laughs, but Frace says he wouldn’t be upset if the audience laughed. “What we’re going for is a high wire act where if we’re successful, people will be a little unsure whether to laugh or cry or do a little bit of both,” he says.

Something like that happened when the melodrama he wrote was performed. “Looking around the room during the performances I saw the kind of reaction I wanted, which was heads shaking, ‘oh no, oh no,’ but then hands covering mouths giggling because they couldn’t believe we were actually going there, doing things that have been cliched. But again, if you really do them fullheartedly, there’s something delightful because of where these cliches came from originally,” he said.

Kayla Lian, who plays Louise, said she has learned a lot more from the experience than how to perform melodrama. “In melodrama,” she said, “the actor must be full of joy on stage. I think that this is a wonderful and necessary goal for all acting. We must want to be watched and seen and be excited to be onstage with our fellow actors. It’s not as easy as it sounds. It’s a great lesson.”

The Two Orphans will be presented April 29 through May 10 in Meany Studio Theater, with preview performances April 26 and 28. Tickets are $10 for students, $12 for seniors, $13 for faculty and staff and $15 for others. Preview tickets are $8 for everyone. Tickets can be purchased through the Arts Ticket Office, 4001 University Way NE, 206-543-4880 or online at http://drama.washington.edu.

If you’d like to get a preview of The Two Orphans, the UW Libraries has a copy of the movie version — a silent film titled Orphans of the Storm, directed by D.W. Griffith in 1921 and starring Lillian and Dorothy Gish.