By Ashley Wiggin, School of Nursing &

Melinda Young, School of Pharmacy

Imagine a pill bottle that could “talk” to you, reminding you when to take medication or how much to take.

New research being led by the UW School of Nursing is examining how talking pill bottles might improve the health, safety and health literacy of certain patients taking medications.

Seth Wolpin, research assistant professor in the Department of Biobehavioral Nursing and Health Systems (BNHS), is among a team of UW faculty members who recently received a two-year, $429,000 National Institutes of Health grant to study that technology.

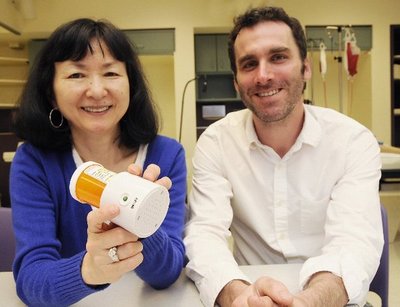

As the grant’s principal investigator, Wolpin will lead co-investigators Annie Lam, senior lecturer from the School of Pharmacy, Ann Kurth and Bill Lober, both associate professors in BNHS, and former School of Nursing faculty and current affiliate professor Donna Berry in assessing the functionality of talking pill bottles.

The pill bottles come with technology that allows pharmacists to record their prescription instructions into a chip with a 60-second recording capability. This technology is intended to help patients with low literacy levels or who are sight-impaired.

“It is very difficult to understand what health care providers are telling you at times,” Wolpin said. “It is easy to forget or misunderstand the information that they give you. This technology could help capture those instructions and make it easier for patients to adhere to their medications.”

Talking pill bottles have yet to become readily available to patients, but can be purchased online. The technology also is in use in California by Kaiser Permanente, a major national health care organization.

Although they would come with a higher price tag than standard pill bottles, their potential long-term benefits — namely an increased ability for certain patients to follow sometimes complex medication directions — might be worth it.

The UW study is in the process of recruiting participants through the Fred Meyer pharmacy in Renton, targeting people with hypertension who have limited health literacy skills. Investigators will study whether audio-assisted medication instructions can have a positive impact on health literacy and medication adherence, Wolpin said, and ultimately improve the health of underserved populations.

Research has shown that nearly half of the 50 million Americans with hypertension are unable to understand the information on their prescription medication. Those with low health literacy rates were even more likely to face challenges in understanding their prescriptions.

“This could be a little step toward overcoming barriers due to low literacy,” said Lam. “[The bottles] can address the limitations of patients who do not have the ability to manage their prescriptions well because either they forget the instructions or they can’t read them. So we’re trying to work with a population that we think will benefit from it the most.”

Added Wolpin: “This is one of the first studies on talking pill bottles in the country. These growing technologies will help to partially address a significant public health problem related to health literacy and medication adherence.”