October 8, 2009

A family history in letters: Graduate School’s Erika Kreger co-edits book on Salmon P. Chase correspondence with daughters

A comment Erika Kreger made in passing to a colleague 17 years ago served as the inspiration for a fascinating historical project that has just now come to fruition.

Kreger, advancement director for the Graduate School, is one of three co-editors of a new book titled Spur Up Your Pegasus: The Family Letters of Salmon, Kate and Nettie Chase, 1844-1873, published by Kent State University Press.

The idea came about, Kreger said, back in 1992 when she was earning a master’s degree and working as a research assistant for James McClure at what is now Claremont Graduate University in California. McClure was the lead editor compiling what would become a five-volume set of the letters of Lincoln-era politician Salmon P. Chase published in the late 1990s. She was transcribing Chase’s hand-written documents and correspondence.

“I started doing more of the family letters and personal letters, and … mentioned that they were more interesting and unique in a certain way — this kind of epistolary relationship between father and daughters.” It was the sort of overlap between professional and personal correspondence not often seen in that era, she said. “It was just a passing comment … and I didn’t think anything else of it.”

Kreger moved on to teach high school, earn a doctorate and become an English professor. She joined the UW’s Graduate School in 2006. After publishing the Chase papers, McClure became editor of the Thomas Jefferson papers at Princeton. Along the way he met Peg Lamphier, a lecturer in history at California State Polytechnic University, in Pomona, Calif., who published a biography of Chase’s elder daughter, Kate, and her politician husband, William Sprague.

But McClure kept Kreger’s comment in mind, and mentioned it to an editor at Kent State University Press, who agreed that a volume of Chase’s family correspondence would be a valuable addition to the historical record. McClure contacted Lamphier and Kreger and suggested they take the project on together part time. And so they began their work. This was in 1996.

“I never focused attention on the fascinating letters between Chase and his daughters until Erika talked to me about them and about scholars’ interest in studying correspondence between parents and children,” McClure said.

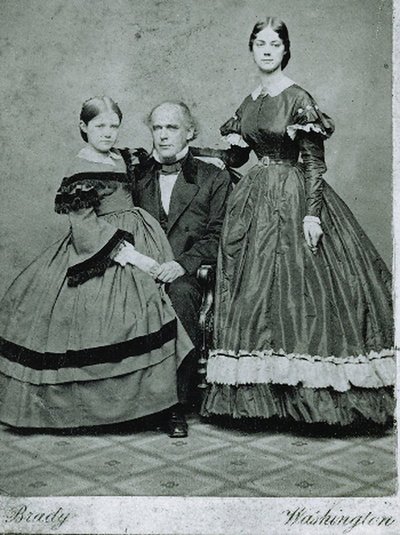

Salmon Portland Chase (1808-1873) was a consummate politician. He served as United States senator from Ohio and as that state’s governor; he was secretary of the treasury under Abraham Lincoln and chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court during Reconstruction. He had powerful presidential ambitions and a resume easily worthy of the White House.

But Chase was also a family man. He had three wives who each died young, and from them had six daughters, only two of whom — Kate and Janet, called Nettie — survived childhood. Chase exchanged letters with Kate and Nettie throughout his career in public life, until his death.

He was a loving father, and doted from afar on his girls, wishing for closeness and guiding them intellectually and spiritually. “What a pity it is,” he wrote Kate, “that one cannot establish some sort of electric communication between mind and paper of which the pen should be the conductive spirit as a wire leads electricity from its source to its reservoir.”

But he was also something of an editorial taskmaster. “I want you to write me every week, and to write just as you would talk, a full account of your doings,” he instructed Kate in 1852, when she was 12. Years later he wrote Nettie, then 16, “I send back your letter with some corrections. I hope you will find time to copy it and return it to me, together with the corrected letter, that I may see whether you understand the corrections I make.”

As the young women matured, Chase wrote to them more as confidantes, even penning letters while doing the business of his offices. “Mr. Dawson of Georgia is making a very loud speech, but it does not interest me enough to make me listen to him,” he wrote to Kate from the Senate floor in 1854. “I prefer to spend the time in the more agreeable occupation of writing you.”

Deciding which letters went in the book was a group effort, Kreger said. Letters by Chase himself were in abundance, it took some detective work to find enough letters written by his daughters to make up the volume. McClure wrote of Kreger’s assistance, “She and Peg selected the letters for the book, and Erika did a lot of long, detailed research in manuscripts and published sources, some of it at far-flung libraries, that really enhanced our understanding of the education of young women and, in particular, Kate’s and Nettie’s schooling.”

Kate and Nettie Chase’s lives took different paths. Kate became hostess for her father and a popular figure in the nation’s capital (incurring the envy and wrath of Lincoln’s troubled wife, Mary Todd). She even had a hand in managing her father’s political activities. Kate married Rhode Island Governor William Sprague and had four children.

“She was very interested and informed at a very early age,” Kreger said of Kate. “Had she been in our era she would have been a politician herself — I think she had that skillset.”

Nettie led a more quiet, conventional life as wife and mother, but satisfied her creative side by publishing children’s books later in life.

“Jim and I wanted to give Nettie her due credit,” Kreger said. “Her story is a little more traditional but also very interesting.” Several of the letters include illustrations from Nettie’s books. “It was nice the way Kent State put those in,” she said.

Spur Up Your Pegasus, Kreger admits, is not the kind of book most people would sit down and read cover to cover. But it provides a new and necessary resource, adding the voices of these bright, accomplished women to the history of a complicated and often misunderstood figure in American history.

It took 17 years from first mention to final product, but Kreger is proud of the result, and credits McClure with “doing the lion’s share of work” for the book.

McClure is quick to return the compliment, saying she was “of absolutely fundamental importance to the project.

“Erika gets huge credit for there even being such a book,” McClure wrote, noting that Spur Up Your Pegasus, now finished and in libraries nationwide, came “from the seed that Erika planted.”