October 8, 2009

Landscape architecture professors write book on community gardens

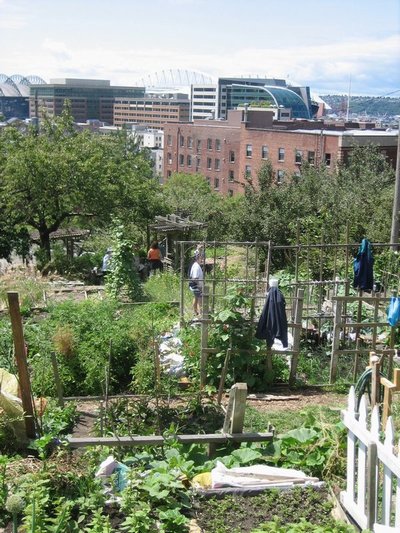

Many cities across North America have community gardens, but only Seattle and a few others include them in urban planning — and it’s helped them thrive.

A new book, Greening Cities, Growing Communities, offers not only insight about the city’s shared gardening plots but practices that could help develop and sustain community gardens elsewhere.

Published this fall by the University of Washington Press ($40, paperback), Greening Cities was written by Jeffrey Hou, associate professor and new chairman of the landscape architecture department at the UW; Julie M. Johnson, a UW associate professor of landscape architecture; and Laura J. Lawson, an associate professor of landscape architecture at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana.

Johnson and Hou will present a book reading at 7 p.m. next Wednesday, Oct. 14, at University Bookstore.

Greening Cities, Growing Communities explains how Seattle is conducive to community gardens: It has active, well-known neighborhoods, a maritime climate good for plant growth, plenty of people interested in gardening and government support for open space.

Seattle has also had various kinds of community gardens, including victory gardens during World War II, but the latest can be traced to the early 1970s, when the Picardo family let a group of students and families grow food for the Neighbors in Need program. Community gardens were subsequently named P-Patches.

The authors of Greening Cities profile six Seattle community gardens, many of which grew from planners and designers listening to needs of the stakeholders, then proposing plans that left significant room for growth and change. The profiles also show the ways community gardens become not only food producers but sources of recreation, vehicles for social justice and means of knitting people together.

First up is Interbay P-Patch, which covers one acre at 15th Avenue West and West Armour Street but has been moved twice, the result of city plans for a golf course. Gardeners got more politically savvy with each move, such that by the second time, they secured a city council resolution promising the same size plot, equal or better than the existing garden in terms of topsoil and irrigation and that the city would both help with the move and provide lumber for new raised beds.

Interbay covers one acre at 15th Avenue West and West Armour Street but it’s been moved twice, the result of city plans for a golf course. Gardeners got more politically savvy with each move, such that by the second time, they secured a city council resolution promising the same size plot, equal or better than the existing garden in terms of topsoil and irrigation and that the city would both help with the move and provide lumber for new raised beds.

The authors say that the experience, tough as it was, helped build a gardening community, and those ties are essential to development and maintenance of community gardens.

Geographic stability has been hard for a number of community gardens, so the Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation now permits P-Patches on its land.

The P-Patch Program has also developed new gardens on a range of neighborhood sites as well as food for food banks, education and job training for young people and the homeless. It has also extended services to seniors and new immigrants. P-Patch is now run by the Seattle Department of Neighborhoods.

Thistle P-Patch is an example of a community garden that primarily serves immigrants. Set on three acres in a utility easement at Martin Luther King Jr. Way and Cloverdale Street in the Rainier Valley neighborhood, it’s typical of community gardens in being an odd, underused parcel.

Asians garden many of the Thistle plots, but methods differ according to nationality. Koreans typically create neat, tidy beds whereas Hmong gardeners skip formal order. Planning thus demands clearly defined plots, and it helps to have a site coordinator with multicultural background.

One gardener talks about the importance of being able to grow Japanese vegetables. “That is a huge difference,” the gardener says, “in both taste and how far our household economy goes.”

The Danny Woo Community Garden at 620 South Main St. in the International District also has many Asian gardeners, many of them seniors. They use the garden not only for food growing but as a way to get out of small apartments. Off-season educational workshops have been organized for them and others to share gardening wisdom and learn about sustainable gardening tools such as organic fertilizer.

Danny Woo has also been a site for UW’s Neighborhood Design/Build Studio led by Steve Badanes, a professor of architecture. In a 10-week quarter, students listened to residents needs, then designed and constructed sophisticated bleacher-style seating.

The more sustainable gardens, say the authors, are hybrids. Organized and led largely by private individuals and groups, they nevertheless tap into money and other help from government entities.

But all is not Eden. “Seattle is a good model for community gardens but there are persistent challenges,” Hou said in an interview. As urban areas, the gardens sometimes face theft and vandalism. Some gardens haven’t had definable edges so attract dumping. Sometimes homeless people become garden problems. Fences solve some hassles; Bradner Gardens Parks at 29th Avenue South and South Grant Street uses artful fences to mark garden boundaries, but authors say there aren’t easy answers to any of the challenges.

In the last chapter of the book, however, they offer lists for people who want to make community gardens happen: Gardeners can lobby policy makers; designers and planners can use their expertise to advocate for such gardens but create open frameworks that allow for garden growth; nonprofits can both provide and help find funding necessary to create and sustain gardens.

Greening Cities was written under the auspices of the Landscape Architecture Foundation as part of its support of case-study research.