December 10, 2009

Class Notes: Exploring Russian science fiction

Class title: Russian 120 — Science Fiction in Russia. Taught by Jose Alaniz, associate professor in the Slavic Languages and Literature Department.

Description: (From the class syllabus.) “We will examine the roots and development of science fiction in Russian literature and cinema, with an emphasis on the Soviet era. Among the questions explored:

- What are the genre’s associations with utopian and revolutionary politics in Russian culture?

- What was its relationship to Socialist Realism?

- What distinguished Russo-Soviet sci-fi from its Western counterpart?

- How did the genre differ from other types of literature?

- What sort of readership did it attract?

- What has been the role of popular culture in Russia through the centuries?

By the end of the course you will have a solid foundation in this understudied Russian literary and cinematic genre.”

Instructor’s views: Alaniz said the class exposes students to writers and works largely unknown in the West, and who were often considered “second rate” in their own country. He said it is a course made of ideas, and that the class compares minor Russian science fiction writers “with what’s going on in the wider world of so-called high art and literature.”

Many of these center on the notion of Utopianism — “an important part of Russian religious thought” — or achieving a paradise on Earth, and come from Russian writers familiar with the utopian/dystopian works of H.G. Wells and Jules Verne.

In the atheistic Soviet vision of this, he said, “suffering is an important part of it. You see even in atheistic Soviet society the strong conviction about the perfectibility of human beings and constructing a paradise on Earth, for example in the 1950s work of Ivan Efremov. In the 1920s especially, a lot was written about the miraculous capacities of machines and the notion of creating robots and cyborgs and perfecting the human race by marrying it with machines.”

He said the course focuses on the Russia Soviet era, which for the most part did not allow free expression. They could “sort of drop hints” to evade censors, but could not be as openly critical or satirical as, say, the English writers George Orwell or Aldous Huxley.

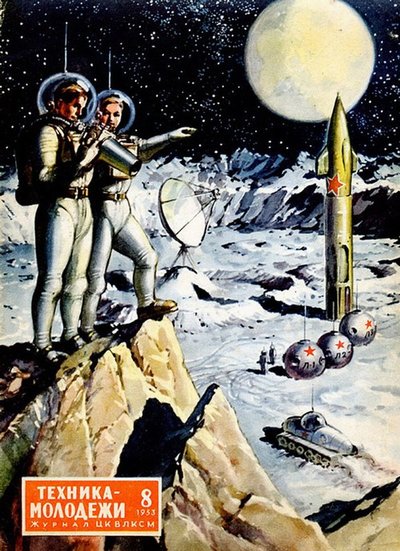

Only later, during the Cold War, he said, and after the death of Stalin, did Russian writers feel more free to openly criticize their own society. Then, he said, “you do start getting more semi-dystopian works” that dare to critique society, like the work of the Strugatsky brothers. Also, Russian science fiction of the 1950s tended to trumpet the accomplishments in the “space race” with the West.

“Science fiction was never just for entertainment,” Alaniz said. “It always reflected an ideological stance.”

Unexpected experiences: Alaniz said while nothing particularly unexpected came up, “As always, students’ insights into the literature affected how I think about it. I enjoyed seeing them question their preconceptions about the genre, especially the Western/American version of sci-fi. I think they also didn’t expect sci-fi to contain so much religious content, as it does in the Russian variant. Finally, they responded about as I expected to this genre’s ‘bad’ writing: overly expository; generally lacking in drama and psychological complexity; and representing women in stereotypical ways.”

Student views: Student Katherine Swigart-Harris wrote in an e-mail, “After hearing stories from my parents and grandparents about the cold war, I have really enjoyed learning what was going on in the minds of Russian authors about Soviet science.”

Student Erin Gustin called the class “extremely enlightening and enjoyable,” adding, “taking this class has allowed me to understand what inspired various authors in not only Russian literature, but other works of science fiction — not only books, but movies.

“Being able to understand the history behind works of literature and cinema allows for more than just entertainment,” Gustin wrote, “it allows for us to not only recognize aspects of our planet’s history, but to be able to understand the flaws in time we all share and make us who we are. I use the word ‘flaws’ because many of the works we covered were critiques of the Soviet Union. These critiques emphasized the extremes of the desire for progress, and the everyday suffering of a human who works to live and contribute to society.

“The works we covered were not all negative, of course — many were quite enjoyable and allowed the absolute sensation of engaging with science fiction to come through in the forms of exploration and discovery.”

Reading and assignments: Required texts include the novels Omon Ra by Viktor Pelevin; We by Yevgeny Zamyatin; Andromeda: A Space-Age Tale by Ivan Yefremov; A Visitor from Outer Space by several authors and the course reader. Each is discussed in class.

Eight of the 10 weeks, students are asked to write half-page papers responding to concepts discussed in the course. They are asked to bundle three of these into a portfolio to be handed in along with the final paper. These equal 30 percent of the overall grade, while class participation is 20 percent, a mid-term is 20 percent and the final paper/project is 30 percent.