January 7, 2010

Crane installation a milestone in construction of Molecular Engineering Building

While many in the campus community were taking a break for the holidays, the workers building the Molecular Engineering Building passed a major milestone. On Dec. 19 a tower crane was installed on the site to speed the moving of materials as the building takes shape.

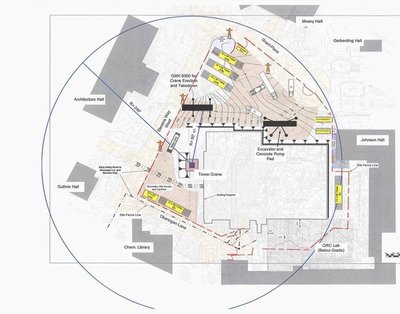

The crane on this site isn’t the tallest one around, or even the tallest on campus. It’s 193 feet — taller than the four-story building under construction (since its foundation is underground, the building’s height above the surface is 178 feet). The crane’s height, said Trevor Thies, the project manager for general contractor Hoffman Corporation, was determined by the need to clear the antennas on the nearby Atmospheric Sciences Building. The crane’s horizontal arm, or jib, has an operating radius of 248 feet, which means that it can swing out over that building, as well as the Architecture Building, the Chemistry Library, Guthrie Hall and Johnson Hall.

But according to Thies, no loads will be suspended above those buildings. “There’s never going to be any loads outside of the fence,” he said. “When the crane is suspending a load, it’s going to be over the work site.”

Cranes have gotten a bit of a bad reputation since one fell over and crashed into a residential building in Bellevue in 2006, killing a man in his apartment. That crane had been erected on an unconventional foundation — it was attached to steel I-beams in an underground parking garage left over from an earlier, unfinished construction project on the site.

The molecular engineering crane has the standard, concrete foundation recommended by its manufacturer. According to Hoffman’s project superintendent, Mike Martinez, the concrete pad is 3 feet 2 inches thick and 27 feet square. It is heavily reinforced. The foundation base was designed by a civil/structural engineer, and the design was reviewed by the UW’s Engineering Services.

According to Steve Tatge, project manager with the UW’s Capital Projects Office, the tower crane components were inspected and certified prior to shipment to the site for installation, inspected again on-site prior to erection and inspected again after erection was complete.

After the accident in Bellevue, the Washington state Legislature passed a law with new regulations for cranes, including more frequent inspections and required certification for crane operators. Thies said that Hoffman has always used certified crane operators on its projects.

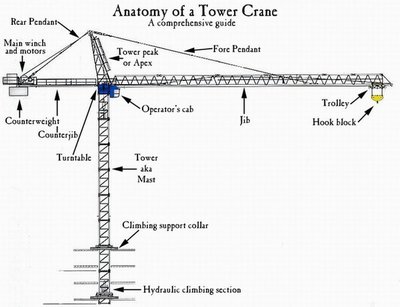

Under ordinary circumstances, operating a tower crane isn’t as dangerous as it might seem, Thies said, unless you count claustrophobia as a risk. Operators typically sit in the crane’s cab for their entire shift, with their own porta-potty for necessary breaks (a good thing, since the cab is accessed via a caged ladder). Operating the machine is done with two foot pedals and a couple of toggle switches. The crane operator also works in tandem with a worker on the ground, called the bell person. The two are connected via radio, and when the crane operator has to move a load he can’t see, the bell person directs him.

“Our bell person is a woman,” Martinez said. “If the crane operator gets sick or can’t operate the crane for some other reason, she’ll fill in.”

Erecting the crane itself required a second crane to bring in the components from trucks on Stevens Way. “It’s like an erector set,” Thies said. “There are nine sections of tower stacked individually on top of each other. They’re all bolted together.”

This particular crane does not exceed its maximum free-standing height and thus does not require a lateral connection to the building to brace it. Nor will it be lifting loads approaching its maximum. The crane has the capacity to lift 9,000 pounds at the end of the jib and 19,000 pounds at the point nearest the cab. Any load that is 75 percent of full capacity, Thies said, is considered a critical load and requires a special safety plan. He said no critical loads will be needed in this project.

Work on the Molecular Engineering Building got under way in late September. Prior to bringing in the crane, the site was excavated, the perimeter shotcrete (concrete that is sprayed-applied under pressure) walls put in place and a temporary power station built.

“The erection of a crane is one of those milestones in a construction process,” Thies said. “You’re able to be so much more efficient in moving materials around the site once you have a crane in place.”

The Molecular Engineering Building site wasn’t the only one with crane activity over the break. The tower crane at the Paccar Hall site was taken down on Dec. 21. The Molecular Engineering Building is expected to be ready for occupancy in the fall of 2011.

To see a webcam for the construction project, <a href=”http://www.atmos.washington.edu/images/webcam1/”>click here.</a>. To learn more about the building, read our earlier article <a href=”http://uwnews.org/uweek/article.aspx?id=52730″>here.</a>