October 21, 2010

Celebration of life for Paul Steven Miller planned Oct. 25

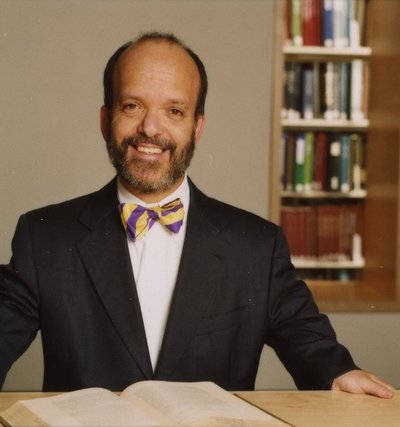

The UW School of Law will have a community gathering to celebrate the life of Paul Steven Miller, the Henry M. Jackson Professor of Law, at 3:30 p.m. on Monday, Oct. 25, in 138 William H. Gates Hall. Overflow seating will be available in room 133 and a reception will follow in room 115. Miller, an international expert in disability and employment who served two U.S. presidents, Barack Obama and Bill Clinton, died on Tuesday, Oct. 19.

Dean Kellye Y. Testy of the law school announced the dedication of the 2010-2011 academic year to Miller. “This year and beyond, we will celebrate his life by infusing his dedication to public service and to equal justice in all we do. We will miss our dear friend and colleague more than we can say,” Testy said.

Miller’s dedication to public service is well-documented. Among his many accomplishments, he was a long-time commissioner of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission who fought for the rights of people with disabilities. He was instrumental in writing the Americans with Disabilities Act, which marked its 20th anniversary several months ago.

After President Clinton appointed him to the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission in 1994, Miller spent much of his time on best ways to enforce the ADA. In the Clinton White House, Miller also served as deputy director of the U.S. Office of Consumer Affairs, White House Liaison to the Disability Community; and a director in the Office of Presidential Personnel.

On hearing of his passing, President Obama issued this statement: “I was saddened to learn of the passing of one of my staffers and a leader in the disability rights movement — Paul Miller. In a world where persons with disabilities are still too often told ‘you can’t,’ Paul spent his life proving the opposite. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and Harvard Law School, Paul went on to become a law professor, disability law expert, one of the longest-serving commissioners of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, an adviser to President Bill Clinton, and later, an invaluable adviser to me.

“But more important than any title or position was the work that drove him. He dedicated his life to a world more fair and more equal, and an America where all are free to pursue their full measure of happiness — and all of us are better off for it. My thoughts and prayers go out to his wife, Jennifer, his daughters, Naomi and Delia, and all whose lives Paul touched.”

At Miller’s professorial installation at the law school in 2008, colleague and college classmate Professor Anna Mastroianni spoke of Miller as a “human catalyst.” Mastroianni went on to describe Miller as “the rare combination of intellectual firepower along with the energy and insights to make the other people he works with better.” She also commented on Miller as a scholar. “Paul has been at the forefront of legal thinking…. While the human genome was being mapped, he immersed himself in the science and thought hard about its potential applications in the workplace.”

Interim UW President Phyllis Wise said, “I first met Paul Miller when I interviewed for the Provost’s position. I realized how much he cared about the UW. Then I got to know him better when he served on the Obama transition team, and I realized how much he cared about the country. More recently I got to know about his wife and children. I realized how much he loved his family, and I learned about his passion for life. We have lost a man of wisdom, integrity, devotion, and compassion. I feel so privileged to have known him and counted him as a friend and colleague.”

Students also recall Miller. “Having Professor Miller as our entry into law school with his patient teaching, goofy jokes, props for torts cases, and serious discussions will stay with my section mates and me for life. He was the one professor last year who took us all to his house for dinner, often went out to coffee with us; let us play with his kids…”

Julie Myers, Miller’s research assistant for nearly three years, remembers Miller as “more than a boss.” Myers, like so many others, considered him a mentor. “He was always on my side, but incredibly measured.”

She continues to describe the person behind the professor. “Music always streamed from Paul’s computer and his printer never seemed to be working properly. The disarray of the physical space was an absolute foil to his smart, self-assured, witty demeanor. Although I didn’t know about his many accomplishments yet, I was impressed. He knew as much about civil rights, as he did about South Park and other pop culture delights.”

Professor Clark Lombardi, Miller’s colleague and long-time friend recalls Miller as person with “a wicked sense of humor, and his self-confidence (which was considerable) was leavened by his ability to view himself with critical distance and to tell exceptionally funny and self deprecating stories at his own expense. I will miss all of that terribly as I think will many others.”

From 2006 to 2009, Miller served as the director of the University of Washington’s Disability Studies Program, an interdisciplinary program that examines the social, cultural, historical and personal experience of disability.

Dr. Benjamin Wilfond, Director of Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics at Seattle Children’s Research Institute and Professor in the Pediatric Department of University of Washington School of Medicine remembers his friend and his legacy. “Miller’s unique contribution to issues related to genetics and disability lie with his approach to arriving at pragmatic but principled approaches. Shortly after Miller arrived in Seattle to lead the UW Disabilities Studies Program, a controversy emerged about using medicine to limit the growth of children with profound disabilities. Miller was the co-principal investigator on a project with the Treuman Katz Center for Pediatric Bioethics at Seattle Children’s and funded by the Greenwall

Foundation and the Simpson Center for the Humanities. The project included two public symposia at the Law School and a sustained engagement of clinicians, scholars, and activists over a year that culminated in a paper to be published in a November, 2010 Hastings Center Report that navigated a course for middle ground that most of this diverse group could agree with. Miller had particular talent in helping people see beyond their own views and reaching pragmatic compromise. He emphasized process, fairness, and a willingness to give weight to all perspectives.”

Miller was born with achondroplasia, a genetic condition that results in dwarfism. After graduating from law school, he drew attention from major law firms, but after face-to-face interviews, none extended offers. According to a Seattle Post-Intelligencer story in 2004, one interviewer told Miller his firm couldn’t hire a dwarf because clients would be put off by a freak.

Miller, however, refused to give up, and eventually landed a job with a firm in Los Angeles where he became a litigator known for deep knowledge of equal-opportunity law.

Current Commissioner of EEOC, Chai Feldblum called Miller “a force of nature both within the disability rights community and generally in the world. He would use humor, strategy, and guts to push for the type of change in this world that he knew would make a real difference in people’s lives.”