October 21, 2010

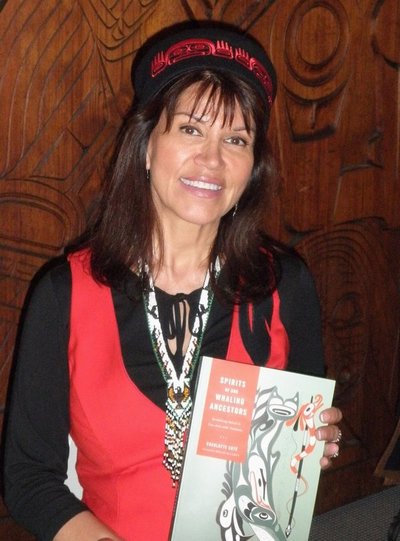

Of tribes and whales: Charlotte Cote publishes ‘Spirits of Our Whaling Ancestors’

When Charlotte Cote was growing up on the western coast of Vancouver Island, she constantly heard stories about whaling, even though no actual whaling had been done there since 1928. Cote, an associate professor of American Indian Studies, is a member of the Canadian Nuu-chah-nulth nation, which is related to the American Makah nation culturally, linguistically and geographically.

“I don’t think there’s one person at home who doesn’t have some design or some piece of art in their personal lives that links to whaling — a whale on a basket, or a piece of clothing, or a piece of art on their walls,” Cote said. “Whaling is so important to our stories and our myths and our teachings. Even the place names around us link us to our whaling tradition.”

No wonder, then, that Cote’s dissertation for her doctoral degree at UC Berkeley had to do with whaling. And now she’s written a book, Spirits of Our Whaling Ancestors, that is aimed at the general public. She’ll be reading from that book at 7 p.m. Thursday, Oct. 28, at the Burke Museum.

Whaling made the news in a big way in 1999 when the Makah conducted a successful whale hunt, their first in many years. The gray whale, hunted almost to extinction by commercial whalers, had made a recovery while on the Endangered Species List from 1970 to 1994, and both the Makah and the Nuu-chah-nulth nations declared that they would revive their whale hunts.

Cote was in Berkeley when her sister called her to tell her the Makahs had killed a whale near Neah Bay. “I was overwhelmed and ecstatic at what the Makah tribe had just achieved,” she wrote in the book.

But not everyone was ecstatic. A loose coalition of marine conservationists, animal rights activists, people from the whale-watching tourism industry and people opposed to the Indian treaties showed up at the hunt and did everything from carry signs and shout slogans to try to physically obstruct the Makah canoe. Since then, the Makah have been tied up in lawsuits that have prevented them from repeating the hunt, although five Makah men killed a whale in an unauthorized hunt in 2007.

Why would the Makah and the Nuu-chah-nulth (who have not yet attempted a modern day hunt) want so much to engage in whaling? After all, the whale is no longer needed for food. In fact, Cote said, most of the native people who shared in the Makah’s whale had never before tasted whale meat. But she said there’s more to it than the obvious.

“It [whaling] is so firmly entrenched in who we are as a people that it’s not just about a whale hunt,” Cote said. “It’s more than that. Everything we have in our physical and spiritual world centers on whales and whaling. So it’s more than just a hunt, it’s more than going out and doing this physical act. It has spiritual elements to it, it has very emotional elements and a strong cultural component that keep it very entrenched in who we are as a people.”

The whale is, in fact, one of three key creatures in the Nuu-chah-nulth and Makah oral traditions. The other two are Thunderbird and Sea Serpent. All three are depicted on the Art Thompson print that graces the cover of Cote’s book. Here’s how she explains the drawing in that book:

“T’iick’in, the great mythical Thunderbird, was the first great whale hunter. The flapping of his wings caused thunder and his flicking tongue brought lightning…. He utilized Itl’ik, Lightning (Sea) Serpent, as a kind of harpoon or spear to throw at a whale to stun it. Once he had dazed the whale, T’iick’in swooped down and picked it up in his mighty claws and took it back to the mountains, where he enjoyed a feast of succulent whale meat and blubber. T’iick’in demonstrated that the iihtuup [whale] could be caught and utilized for food and tools.”

When the Makah killed their whale, they followed many traditional processes, augmented by modern tools. The hunters involved trained for months and performed ritual cleansing to be ready for what they were to do. They chased the whale in a traditional canoe and threw a harpoon at it, but then they used a gun to kill it, because otherwise it would have taken days for it to die. After the whale was brought to the beach, there were further ceremonies, thanking the whale for giving up its life for the people. The Makah held a potlatch to celebrate the occasion.

Cote has a personal connection to whaling. Her great-great-grandfather was raised to be a whaler; it was passed down to him from both sides of his family. He saw, however, that whales were becoming scarce, and he became a sealer instead. In her book, Cote hearkens back to him and other ancestors.

“I would never say this is a book that I wrote,” she said. “It’s a book that came from the voices of my community and from the spirits of the people who have passed on who helped me and guided my heart as I wrote this.”

She’ll be joined by a number of family members at the Oct. 28 event. “We’re going to share some of our songs and dances with the people there,” Cote said. “I’m going to talk a bit about the whaling tradition, about whaling in the context of artistic expression. Then I’ll read a little bit out of the book, mainly the chapter where I focused on my personal story. I’ve done a lot of presentations on the anti-whaling discourses. But I don’t want to focus on that. I want to focus on the positive aspects in my book. So I’ll probably read about the stories I heard when I was growing up, about my grandfather passing down these amazingly rich whaling narratives and how they reinforced all our traditions and kept them alive.”

The event is free and open to the public.