August 4, 2003

Ultrasound imaging advance improves prostate cancer treatment

For the estimated 140,000 U.S. men diagnosed annually with localized prostate cancer, radioactive seed implantation is fast becoming a preferred alternative to standard treatments involving removal of the prostate gland or external-beam radiation therapy. Unfortunately, many patients have had to endure expensive and time-consuming medical imaging tests to determine whether they are eligible for the new treatment.

That assessment can now be made in minutes rather than days, and at a fraction of the cost, using a new ultrasound imaging technology developed by researchers at the University of Washington and Seattle Prostate Institute. The technology also will help surgeons to more accurately place the radioactive seeds according to the treatment plan in a significant number of cases, the researchers say.

“This improvement will allow physicians to make better treatment decisions and to make them immediately known to the patient,” says Dr. Peter Grimm, executive director of the Seattle Prostate Institute and a pioneer in seed implantation treatment, or brachytherapy. Grimm developed the new ultrasound imaging protocol with Yongmin Kim, professor of electrical engineering at the UW, and Sayan Pathak, a graduate student in bioengineering.

“If you can help doctors and patients, while saving time and money, it not only is a dream come true for the researchers but also benefits the entire medical establishment,” adds Kim, a leading expert in medical imaging and director of the UW Image Computing Systems Laboratory. “Our technology addresses a problem faced by thousands of patients, and we expect it to be readily embraced for clinical use.”

Every year, prostate cancer strikes 185,000 Americans and results in nearly 40,000 deaths, making it the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the second leading cancer-related cause of death among men after lung cancer. During the past decade, brachytherapy has emerged as a successful and cost-effective outpatient treatment for localized prostate cancer. About 10 percent to 15 percent of patients with localized prostate cancer currently are being treated with brachytherapy, and Grimm expects that proportion to rise steadily.

Brachytherapy involves precise placement of radioactive seeds into the prostate gland to kill cancer cells. Guided by an external template and ultrasound imaging, the surgeon uses a needle to implant the seeds according to a pre-determined plan. To be successful, however, the surgeon must be able to pass the needle under the patient’s pubic arch bone to reach all parts of the prostate gland. In 20 percent to 40 percent of cases, the pubic arch will interfere with the surgeon’s needle. Since brachytherapy provides only one chance to place the seeds correctly, Grimm says, surgeons need to know whether pubic arch interference exists before they begin the procedure.

To make that assessment, an ultrasound study is first done to determine the size and shape of the patient’s prostate gland. If the volume of the prostate is 40 cubic centimeters or less, pubic arch interference is rarely encountered. If the prostate volume is 60 cubic centimeters or greater, interference is almost always present. In cases where the prostate volume is 40-60 cubic centimeters, the position of the pubic arch bone becomes critically important. A separate X-ray computed tomography (CT) scan has been required to effectively visualize the pubic arch bone.

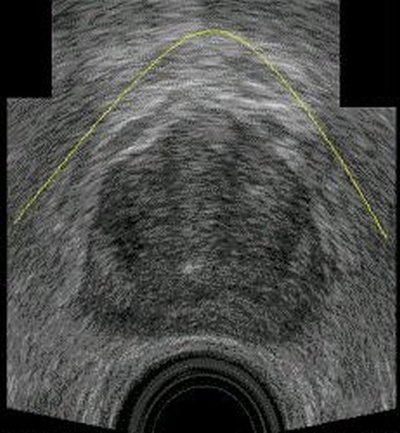

The CT scan of the pubic arch bone is overlaid with an ultrasound image of the patient’s prostate gland to determine whether a surgeon would encounter interference during the brachytherapy procedure. However, CT scans cost up to $500 and are generally available only at hospitals and large clinics that can afford the $1 million machines. Patients can wait a week or more, with their treatment plan up in the air, to have the CT study done and get the results to their doctor. In contrast, ultrasound scans cost less than $100 and can be done in most doctors’ offices, with the results available immediately. Unfortunately, conventional ultrasound technology historically has been unable to accurately detect the pubic arch bone.

“Bone tends to scatter and weaken the ultrasound waves and create a lot of visual noise in the image,” explains Kim, who has a two-decade track record of imaging innovations. “We developed image enhancement technology to reduce the visual noise and significantly increase contrast in ultrasound imaging of the public arch bone.”

The new technology enables doctors to see the prostate gland and pubic arch bone in a single ultrasound image and to assess pubic arch interference within minutes of the patient scan. In fact, most of that time is consumed transferring data from the ultrasound machine to a computer for image processing. Ultimately, Kim says, the new technology will be installed within the ultrasound machine itself so doctors can view the combined prostate gland-pubic arch image in real time as the patient is being scanned.

In addition, Grimm says, the ultrasound technology allows doctors to examine their patients in the same tucked-knee position that they will be in for the brachytherapy procedure. CT exams require patients to lie in a prone position, which changes the relationship of the pubic arch bone to the prostate and makes it more difficult to assess whether pubic arch interference will be encountered during surgery.

In pre-clinical studies at the Seattle Prostate Institute, the new ultrasound imaging technology accurately predicted whether public arch interference was present in all but two of 307 planned needle insertion points. This is well within clinically accepted limits, Kim says.

“The CT essentially offers an expensive and time-consuming guess. Obviously, as a doctor, I want to reduce guesswork as much as possible,” Grimm adds. “The obvious advantage of the ultrasound protocol is that it accurately reproduces the anatomical situation that the surgeon will encounter in the operating room. This gives surgeons better information and improves the quality of care they can provide.”

A paper describing this research has been accepted for publication in the journal IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging.

###

For more information, contact Grimm at (206) 215-2480 or peter@grimm.com, Kim at (206) 685-2271 or kim@ee.washington.edu, and Pathak at (206) 221-5169 or sayan@u.washington.edu.