July 11, 2000

Extra oxygen improves survival odds for climbers on Mount Everest, K2

Climbers who conquer the world’s highest peak are about one-third as likely to die during descent if they use supplemental oxygen during the journey than if they rely only on the limited oxygen in thin mountain air, a University of Washington researcher has found.

Of the 1,173 people who successfully scaled Mount Everest on the Nepal-Tibet border from 1978 through 1999, the death rate during descent was 8.3 percent for those not using supplemental oxygen, compared with 3 percent for those using extra oxygen, said Raymond Huey, a UW zoology professor. Supplemental oxygen was used by 1,077 climbers who reached Everest’s summit and 32 of them died during the descent, he found, while eight of the 96 climbers who did not use supplemental oxygen perished on the way down.

A similar, more striking, pattern emerged on K2, the world’s second-highest mountain, which is on the Pakistan-China border about 800 miles from Everest. On the steeper, more rugged K2, none of the 47 successful climbers who used supplemental oxygen died during descent. But 22 of 117, or nearly one in five (18.8 percent), of those not using bottled oxygen perished after reaching the summit. Many of those deaths came during two violent storms in 1986 and 1995.

The comparisons only used figures for climbers who successfully reached the two peaks because data on unsuccessful expeditions were not readily available.

The research by Huey and Xavier Eguskitza, a Himalaya mountaineering historian, is the first to quantify the effects of supplemental oxygen in climbing Everest and K2. It is published in the July 12 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“The finding that climbers using supplemental oxygen have higher survival rates might reflect the benefits of extra oxygen in reducing the physical and mental deterioration that is inevitable at extreme altitude,” Huey said. “But our data don’t necessarily imply cause and effect. Another explanation is that climbers using supplemental oxygen survive better because they are more careful in general or have better support teams, but that idea would be hard to test quantitatively.”

Huey has been interested in, and has read extensively about, mountaineering for much of his life. He became intrigued by the oxygen issue several years ago after hearing an address at the UW by noted mountaineer Reinhold Messner. In 1978, Messner and Peter Habeler became the first climbers to scale the 29,035-foot Everest without using bottled oxygen. Two years later Messner became the first to climb the peak alone, again without bottled oxygen.

In his presentation at the UW, Messner argued against climbing in large, military-style expeditions that were the main way of climbing in the Himalayas during the 1970s. He felt that climbing in small groups, Alpine style, should be safer and more successful, Huey said. Messner contended that such groups can move more quickly and thus spend less time on the mountain, which should make them less vulnerable to avalanches and medical problems, the leading causes of death among mountaineers.

Messner also argued against using supplemental oxygen, saying it results in downgrading Everest to a 20,000-foot mountain.

“Messner felt the use of supplemental oxygen was unsporting because, in effect, it lowers the physiological height of a peak,” Huey said.

He realized Messner’s statements could be viewed as scientific hypotheses that could be tested and he began working with Eguskitza, examining data to see whether oxygen use influenced safety. That research was conducted under a fellowship Huey was awarded from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Huey and Eguskitza also plan to measure success rates for large expeditions against those for small groups.

The danger associated with climbing Mount Everest was underscored in 1996 when eight people from two expeditions – including group leaders Scott Fischer of Seattle and Rob Hall of New Zealand – died when a sudden storm engulfed their parties. Both groups were using bottled oxygen. That incident, one of the deadliest days in the mountain’s history, became the subject of several books.

“The deaths of so many climbers during that storm raised the average death rate for climbers using supplemental oxygen,” Huey said. “Even so, their death rate is still only one third that of climbers not using supplemental oxygen. Climbing these big peaks even with supplemental oxygen is still very dangerous.”

###

For more information, contact Huey at (206) 543-1505, (206) 543-1620 or hueyrb@u.washington.edu

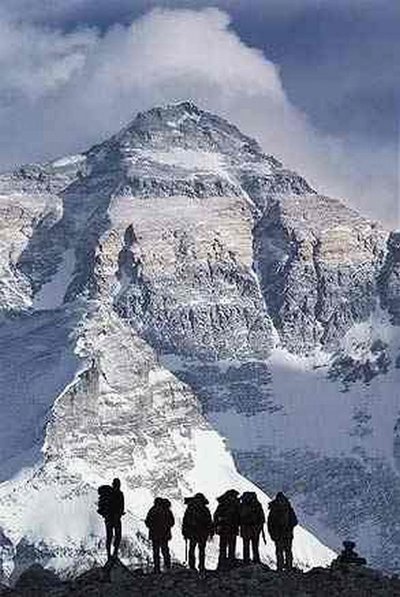

For information about using the image of Mount Everest included in this release, contact Deirdre Skillman, Research & Permissions Editor, Art Wolfe Inc., Seattle, (206) 332-0993 or skillman@artwolfe.com