January 26, 2006

The Smallest Witnesses: Odegaard exhibit features drawings by children in Darfur

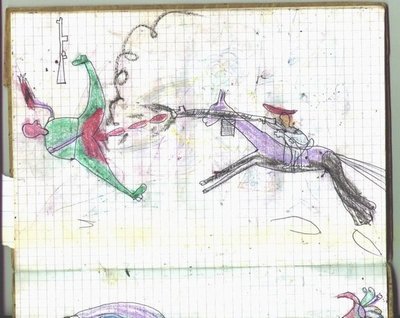

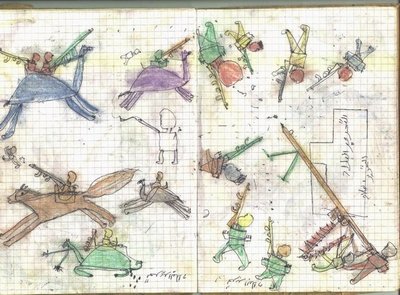

A professor and a visiting fellow from the University will be among those speaking when a new exhibit, The Smallest Witnesses: The Conflict in Darfur Through Children’s Eyes, comes to the Odegaard Library Feb. 1. The exhibit features 27 drawings by children from the Darfur region of Sudan who escaped air raids and ground attacks. The children, some as young as 8 years old, witnessed the destruction of their homes, and now live in refugee camps in Chad.

“The drawings show what children in the war have seen,” said Michael Tarlowe, from SaveDarfurWashingtonState, one of the exhibit’s co-sponsors. “We want the community to learn about the conflict, to discuss the human rights of children, and hopefully, to feel moved to act.”

Human Rights Watch researcher Olivier Bercault and his colleague gave the children crayons and paper while interviewing their parents last year in Chad. Without instruction or prompting, the children produced disturbing and vivid images of the atrocities they had seen. The drawings, with their unique visual vocabulary of war, give a forceful voice to the youngest victims of the war.

Nancy Farwell, the director of the African Studies Program in the Jackson School and a faculty member in the School of Social Work, and Amna Ibrahim, a Population Leadership Fellow who is working as youth and adolescent coordinator for UNICEF in Sudan, will be speaking at a panel to be presented at 6:30 p.m. Feb. 1 at the library, as part of the opening reception for the exhibit. Farwell studies the impact of war on children and worked in another African nation, Eritrea, during its long war with Ethiopia. Ibrahim has worked with relief organizations in Sudan, including with traumatized children.

“Children in a sense are doubly traumatized during war because they experience what happens to them individually, and they’re also affected by what happens to their families and communities,” Farwell said. “Then of course there’s a complete disruption of the support networks for both families and communities, making recovery difficult.”

Open warfare erupted in Darfur, in western Sudan, in early 2003 when the two loosely allied rebel groups, the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army and the Justice and Equality Movement, attacked military installations. This was followed closely by peace agreements to end the 20-year-old civil war in the south of Sudan which allocated government positions and oil revenue to the rebels in the south.

At that time rebels in Darfur, seeking an end to the region’s chronic economic and political marginalization, also took up arms to protect their communities against a 20-year campaign by government-backed militias recruited among groups of Arab extraction in Darfur and Chad. These “Janjaweed” militias have over the past year received government support to clear civilians from areas considered disloyal to the Sudanese government. Militia attacks and a scorched-earth government offensive have led to massive displacement, indiscriminate killings, looting and mass rape, all in infringement of the 1949 Geneva Convention that prohibits attacks on civilians.

“The situation is very complicated,” Ibrahim said. “The rebels are against the government, and all of it is overlaid by tribal loyalties. Now a few weeks ago, Chad announced that they are in a war situation with Sudan. So now the problem is transferred from Sudan to the bordering country. My worry is that the situation in Sudan will affect the whole rest of Africa.”

The war has already displaced an estimated 2.4 million people. According to the U.N., as many as 200,000 people may have died in the past two years.

Farwell and Ibrahim agree that one of the crucial things for children in such situations is to have a sense of normalcy wherever they are. “We need to pay attention to building on the resilience of the people, to resume their livelihoods after the conflict ends,” Farwell said.

The drawings that the children did can be helpful to the recovery process, although Ibrahim said that drawing isn’t the natural creative expression in her culture, which is more oriented to singing and dancing. “One important thing in resolving trauma is to tell the story and tell the story in enough ways that it comes to a new resolution,” Farwell said. “You don’t want it to be a repetitive story that remains fixed.”

The groups that sponsored the exhibit hope to raise awareness about the situation in Darfur, not just to raise money, but to inspire viewers to demand that the United States government support a stronger multinational force to protect the citizens of Darfur.

Ibrahim urges people who are interested in the situation to think long term. “This is a rooted structural problem and it’s going to require a rooted structural solution, based on an understanding of the culture,” she said. “This is not just about addressing the current emergency.”

Also speaking as part of the opening reception panel is Olivier Bercault from Human Rights Watch, who collected the drawings. Bercault has documented human rights violations in Sudan, Chad, Afghanistan and Iraq. Fred Abrahams, senior emergency researcher for Human Rights Watch, will be the moderator. The reception is free and open to the public.

The exhibit will be at Odegaard through Feb. 22. It is co-sponsored by Human Rights Watch (www.hrw.org), the American Jewish Committee (www.ajcseattle.org), the Washington State Holocaust Education Resource Center (www.wsherc.org) and SaveDarfurWashingtonState (www.savedarfur.org). For additional photos, see http://hrw.org/photos/2005/darfur/drawings/