October 4, 2001

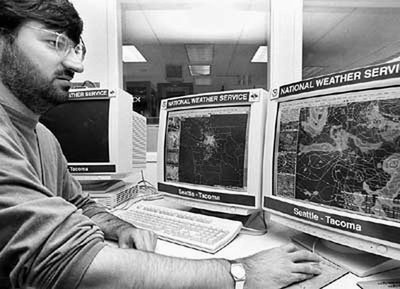

Northwest coast needs more Doppler radar installations, scientist says

Coastal Washington and Oregon are being left to the mercy of Mother Nature because federal Doppler radar installations don’t provide meteorologists with enough information to come up with more accurate short-term forecasts, a UW scientist says.

“We don’t have very much useful information offshore, and over much of the coast we are blind,” said Cliff Mass, a UW atmospheric sciences professor who leads an effort to improve Northwest forecasting using high-resolution computer predictions.

Mass says the economic and safety implications are serious. He’d like to see at least one new radar installation along the coast to give meteorologists a look at conditions up to several hundred miles offshore.

The National Weather Service upgraded its Doppler radar installations nationwide in the late 1980s and early 1990s. However, none was installed along the Washington and Oregon coast.

Instead, they were placed on Camano Island in Washington and at Portland and Medford in Oregon. However, the Olympic and coastal mountains prevent those units from providing adequate coverage along the coast, and their off-coast coverage is almost non-existent.

“We got short shrift,” Mass said. “The problem is that they put the radars in populated areas, but we have all these mountains blocking our view to the ocean.”

The lack of coastal radar seriously diminishes the ability to provide accurate short-term forecasts (covering 24 hours or less) because meteorologists don’t have precise information about weather systems that lie off the coast and are headed toward land, Mass said. That has serious implications for the fishing industry, the military, pleasure boaters and any traffic entering the Strait of Juan de Fuca or the Columbia River.

It also affects operations sensitive to rapidly changing weather conditions, such as the much publicized salvage efforts of the New Carissa, a ship that ran aground near Coos Bay, Ore., in February 1999, spilling some 70,000 gallons of heavy fuel oil.

“There have been some real forecast failures because we can’t see upstream,” Mass said. A classic example, he said, was on May 15 this year when warnings were issued for a high windstorm that never developed. Satellite images and other data gave sketchy indications of the presence of a low-pressure system and a computer model using that information indicated a strong windstorm would hit Western Washington.

However, the low-pressure system actually was moving north into Canada, and Doppler radar would have pinpointed that fact very quickly, Mass said, so the bogus warnings likely would never have been issued or would have been dropped much earlier.

“We could give very solid 6- to 12-hour forecasts,” he said. “It would basically eliminate major forecast busts caused by not being able to see where systems are and knowing when they are going to hit the coast.”

The current Weather Service Doppler radars do not cover the Long Beach Peninsula in Washington, a popular vacation spot, and it is impossible to monitor flooding on the southern flank of the Olympic Mountains, where rivers can swell quickly on their way to more populated areas, Mass said.

The problem can be solved by installation of coastal radar at Westport, Wash., and Florence, Ore., to gather reliable data offshore and along the coast. If only one can be installed, Mass would opt for Westport because that would provide coverage for both the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Columbia River.

But securing the radar is likely to require congressional action, since the Weather Service and its parent agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, do not have the spare cash in their budgets. Mass estimates each installation would cost about $5 million. But he said that is far less than what would be saved by being prepared for bad storms – fishing vessels not going out when it appears conditions will be treacherous, for instance – or by not having to bear the expense of preparing for a storm that won’t materialize.

“One bad forecast can cost what one radar installation costs,” he said. “When you really analyze the costs, a bad forecast can cost millions.”