October 18, 2007

Earliest evidence for modern human behavior found in South African cave

Evidence of early humans living on the coast in South Africa, harvesting food from the sea, employing complex small stone tools and using red pigments in symbolic behavior 164,000 years ago, far earlier than previously documented, is being published in the Oct. 18 issue of the journal Nature. The international team of researchers reporting the findings includes Tom Minichillo, an affiliate assistant professor of anthropology at the UW and the King County Department of Transportation archaeologist.

“Our findings show that 164,000 years ago in coastal South Africa humans expanded their diet to include shellfish and other marine resources, perhaps as a response to harsh environmental conditions,” said Curtis Marean, a paleoanthropologist with the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University who headed the research team “This is the earliest dated observation of this behavior.”

Further, the researchers report that also occurring with this diet expansion is a very early use of pigment, likely for symbolic behavior, as well as the use of bladelet stone tool technology, previously dating to 70,000 years ago.

These new findings not only move back the timeline for the evolution of modern humans, they show that lifestyles focused on coastal habitats and resources may have been crucial to the evolution and survival of these early humans.

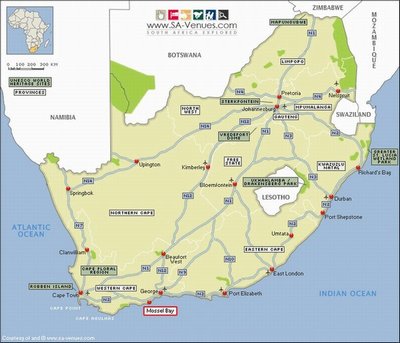

After decades of debate, paleoanthropologists now agree the genetic and fossil evidence suggests that the modern human species, Homo sapiens, evolved in Africa between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago. Yet, archaeological sites during that time period are rare in Africa. However, the researchers found a rich site about 250 miles east of Cape Town, South Africa, near the town of Mossel Bay along the Indian Ocean.

The Middle Stone Age, dated between 35,000 and 300,000 years ago, is the technological stage when anatomically modern humans emerged in Africa, along with modern cognitive behavior. When, however, within that stage modern human behavior arose is currently debated, added Marean, who is a professor of human evolution and social change.

The material found in one of the caves at Pinnacle Point is beyond the range of radiocarbon dating. But firm dates were obtained using two advanced and independent techniques — uranium series that dated speleothem, the material of stalagmites, and optically stimulated luminescence that dates the last time individual grains of sand were exposed to light.

“Generally speaking, coastal areas were of no use to early humans — unless they knew how to use the sea as a food source,” said Marean. “For millions of years, our earliest hunter-gatherer relatives only ate terrestrial plants and animals. Shellfish was one of the last additions to the human diet before domesticated plants and animals were introduced.”

Before, the earliest evidence for human use of marine resources and coastal habitats was dated about 125,000 years ago. “Our research shows that humans started doing this at least 40,000 years earlier. This could have very well been a response to the extreme environmental conditions they were experiencing,” he said.

The researchers also found a variety of stone tools including what archaeologists call bladelets — tiny blades fashioned from quartzite and quartz. They are smaller than the width of the nail on a human little finger and a little longer than one inch. The bladelets could be attached to the end of a stick to form a point for a spear, lined up like barbs on a dart or used independently as a cutting tool like a pen knife, according to Minichillo.

“These tools were not made accidentally, because we found so many of them, as well as the cores from which they were manufactured. This supports the idea that the tool kits of the earliest Homo sapiens had more variety than they are traditionally given credit for,” said Minichillo. “Ordinarily older things, such as tools, are bigger than newer ones. Bladelets are the first small objects recognizable as a tool.

The researchers also found evidence that the people occupying the cave were using pigments, especially red ochre, in ways that appear to be symbolic. Archaeologists view symbolic behavior as one of the clues that modern language may have been present. The modified pigments are the earliest securely dated and published evidence for pigment use.

“Coastlines generally make great migration routes,” Marean said. “Knowing how to exploit the sea for food meant these early humans could now use coastlines as productive home ranges and move long distances.”

Results reporting early use of coastlines are especially significant to scientists interested in the migration of humans out of Africa. Physical evidence that this coastal population was practicing modern human behavior is particularly important to geneticists and physical anthropologists seeking to identify the ancestral population for modern humans.

“This evidence shows that Africa, and particularly southern Africa, was precocious in the development of modern human biology and behavior. We believe that on the far southern shore of Africa there was a small population of modern humans who struggled through the glacial period 125,000 to 195,000 years ago using shellfish and advanced technologies, and symbolism was important to their social relations. It is possible that this population could be the progenitor population for all modern humans,” Marean said.

“The oldest view that early Homo sapiens didn’t have full modern behavior was built largely on an absence of evidence,” added Minichillo. “Now we have data that doesn’t match that idea. It may be that early modern humans had that ability when they first appeared on the landscape.”

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation’s Human Origins: Moving in New Directions (HOMINID) program.

In addition to Marean and Minichillo, co- authors of the paper are Miryam Bar-Matthews of the Geological Survey of Israel, Erich Fisher of the University of Florida, Paul Goldberg of Boston University, Andy I.R. Herries of the University of New South Wales in Australia, Zenobia Jacobs of the University of Wollongong in Australia, Antonieta Jerardino of the University of Cape Town in South Africa, Panagiotis Karkanas of Greece’s Ministry of Culture, Ian Watts from London, Peter J. Nilssen of the Iziko South African Museum and Arizona State University graduate students Erin Thompson, Hope Williams and Jocelyn Bernatchez.