May 1, 2008

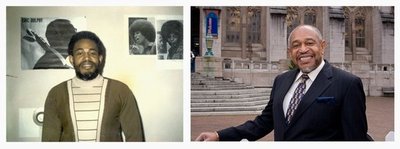

‘Elder statesman’ Pitre helped plant seeds of change in the 1960s

When Emile Pitre arrived at the UW in the fall of 1967, he had already overcome a number of barriers. The son of a sharecropper in Louisiana, he was the first of the eight children in his family to graduate from high school. Then he became the first in his high school to go to college on a full scholarship. Buoyed by the support he received at historically black Southern University, he was accepted for graduate school in the UW’s chemistry department.

“I came here because another student at Southern had come here, and also because I’d been told that Seattle was very progressive, that it didn’t have the prejudice that we did down South,” Pitre said.

But soon after Pitre’s arrival, a white student called him the N word. “That helped me realize that prejudice existed all over, so joining the Black Student Union and being involved in the struggle seemed to me to be an appropriate thing to do.”

Pitre, who is now associate vice president for minority affairs, is among the members of the 1968 Black Student Union who will be honored with the Charles E. Odegaard Award at Celebration 2008, slated for Wednesday, May 7, at the HUB. The event will also honor the winners of the Educational Opportunity Program’s scholarships. It’s all part of a celebration of 40 years of diversity at the UW, most of which Pitre has been part of. (Read our story about the UW’s celebration of 40 years of diversity <a href=http://www.uwnews.org/uweek/uweekarticle.asp?cachecommand=create&articleID=41470>here</a>.)

The Black Student Union was formed in January of 1968, evolving out of a group that had formerly been called the Afro American Student Society, Pitre said. “The society was purely a social support organization, but the BSU was all about political action.”

The change came about after a group of students attended a youth conference in California and returned fired up with the idea of changing the University, and through it, society. Pitre was not among those who went, but he was very receptive to their message.

“I had begun to go through a transformation, even when I was at Southern University,” he said. “H. Rapp Brown, who later became the leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was a student at Southern University, and things had started to change on campus. Then Stokely Carmichael came to give a talk at Southern, telling us we should call ourselves black rather than Negro. When I heard Stokely Carmichael, I was starting to change my consciousness.”

So were the students at the UW when they decided to change their name to Black Student Union and to push for a more diverse campus. At the time, the University had only one African American professor, and of the 32,000 students enrolled, only 4 percent were students of color. Nonwhite staff members were concentrated in the most unskilled jobs.

Over a several month period, BSU members discussed their concerns and drafted a letter to then-President Charles Odegaard, demanding that the University recruit more students of color and support them after their arrival, create a Black Studies Program for academic study of black history and culture and recruit more faculty, staff and administrators of color. It was sent on May 6.

“President Odegaard was understanding and we believe was very sympathetic to what we wanted as students,” Pitre said. “His daughter later told us that he used to discuss issues with her, and that he wondered why the University didn’t serve a wide cross-section of the citizenry. So he believed things needed to change.”

But he couldn’t make things happen overnight, and the students became impatient. On May 20, they held a sit-in in Odegaard’s office. Pitre participated, but with some misgivings.

“I was a little concerned about the sit-in because I had a fellowship and I could have lost it. I could have been kicked out of school,” he said. “But I got caught up in the movement and was willing to take the risk for what I considered a just cause.”

The sit-in lasted only a little over four hours, ending with Odegaard’s promise to move forward on the demands. And indeed, recruitment of students of color did begin almost immediately. To support those students, who were assumed to be coming in underprepared, the University set up what was then known as the Special Education Program (now the Educational Opportunity Program). It also began planning for a Black Studies Program.

Pitre suffered no repercussions for his role in the sit-in, and continued in his graduate program. He also remained active in the BSU as other developments came along, including the founding of the Ethnic Cultural Center and the hiring of Samuel Kelly as the first vice president for minority affairs. But in 1972 he left the UW.

By 1982 he was working as a chemist in Greensboro, SC, when he got a call offering him a job as a chemistry instructor at the Instructional Center, where EOP students get academic help. Even though it meant a pay cut, Pitre accepted.

“I missed Seattle,” he said, “and I missed academia. I’d always liked being in the Instructional Center environment because it was a position where I could help others do better. It was a natural fit.”

He became the center’s assistant director in 1985 and director in 1989. While there, he began collecting data to try to learn what impact the tutoring had on students’ performance in classes, access to majors and graduation rates. He moved to Minority Affairs and Diversity in 2002, and has been there ever since.

“I’ve taken to calling Emile our elder statesman,” said Sheila Edwards Lange, vice president for minority affairs and vice provost for diversity. “He has tremendous institutional memory and has built strong relationships on campus and beyond. I often look to his judgment on decisions I need to make.”

Pitre brought his data analysis skills to Minority Affairs, and now is attempting to track all underrepresented students in the same way he tracked those at the Instructional Center. Lange calls him a “genius” with data, and has placed him in a position where that is his primary responsibility.

“I miss the contact with students,” Pitre said, “but the more I do this job the more I recognize the value it has, not only within Minority Affairs but campus wide.”

Looking back at the movement he was part of 40 years ago, and an association with the UW that is nearly that long, Pitre said he feels proud. “If we look at the number of students of color who have graduated since the event [the sit-in] I like to call the event that changed the University of Washington forever, there have been 49,000. It was one of the defining moments in the history of UW.”