January 21, 2009

New data show much of Antarctica is warming more than previously thought

Scientists studying climate change have long believed that while most of the rest of the globe has been getting steadily warmer, a large part of Antarctica — the East Antarctic Ice Sheet — has actually been getting colder.

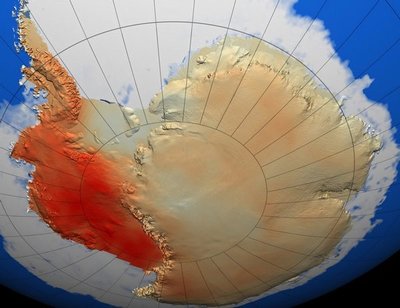

But new research shows that for the last 50 years, much of Antarctica has been warming at a rate comparable to the rest of the world. In fact, the warming in West Antarctica is greater than the cooling in East Antarctica, meaning that on average the continent has gotten warmer, said Eric Steig, a University of Washington professor of Earth and space sciences and director of the Quaternary Research Center at the UW.

“West Antarctica is a very different place than East Antarctica, and there is a physical barrier, the Transantarctic Mountains, that separates the two,” said Steig, lead author of a paper documenting the warming published in the Jan. 22 edition of Nature.

For years it was believed that a relatively small area known as the Antarctic Peninsula was getting warmer, but that the rest of the continent — including West Antarctica, the ice sheet most susceptible to potential future collapse — was cooling.

Steig noted that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, with an average elevation of about 6,000 feet above sea level, is substantially lower than East Antarctica, which has an average elevation of more than 10,000 feet. While the entire continent is essentially a desert, West Antarctica is subject to relatively warm, moist storms and receives much greater snowfall than East Antarctica.

The study found that warming in West Antarctica exceeded one-tenth of a degree Celsius per decade for the last 50 years and more than offset the cooling in East Antarctica.

Co-authors of the paper are David Schneider of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo., a former student of Steig’s; Scott Rutherford of Roger Williams University in Bristol, R.I.; Michael Mann of Pennsylvania State University; Josefino Comiso of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.; and Drew Shindell of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City. The work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation.

The researchers devised a statistical technique that uses data from satellites and from Antarctic weather stations to make a new estimate of temperature trends.

“People were calculating with their heads instead of actually doing the math,” Steig said. “What we did is interpolate carefully instead of just using the back of an envelope. While other interpolations had been done previously, no one had really taken advantage of the satellite data, which provide crucial information about spatial patterns of temperature change.”

Satellites calculate the surface temperature by measuring the intensity of infrared light radiated by the snowpack, and they have the advantage of covering the entire continent. However, they have only been in operation for 25 years. On the other hand, a number of Antarctic weather stations have been in place since 1957, the International Geophysical Year, but virtually all of them are within a short distance of the coast and so provide no direct information about conditions in the continent’s interior.

The scientists found temperature measurements from weather stations corresponded closely with satellite data for overlapping time periods. That allowed them to use the satellite data as a guide to deduce temperatures in areas of the continent without weather stations.

“Simple explanations don’t capture the complexity of climate,” Steig said. “The thing you hear all the time is that Antarctica is cooling and that’s not the case. If anything it’s the reverse, but it’s more complex than that. Antarctica isn’t warming at the same rate everywhere, and while some areas have been cooling for a long time the evidence shows the continent as a whole is getting warmer.”

A major reason most of Antarctica was thought to be cooling is because of a hole in the Earth’s protective ozone layer that appears during the spring months in the Southern Hemisphere’s polar region. Steig noted that it is well established that the ozone hole has contributed to cooling in East Antarctica.

“However, it seems to have been assumed that the ozone hole was affecting the entire continent when there wasn’t any evidence to support that idea, or even any theory to support it,” he said.

“In any case, efforts to repair the ozone layer eventually will begin taking effect and the hole could be eliminated by the middle of this century. If that happens, all of Antarctica could begin warming on a par with the rest of the world.”

###

For more information, contact Steig at (206) 685-3715, (206) 543-6327 or steig@ess.washington.edu.