August 10, 2009

Life and death in the living brain: Recruitment of new neurons slows when old brain cells kept from dying

Like clockwork, brain regions in many songbird species expand and shrink seasonally in response to hormones. Now, for the first time, University of Washington neurobiologists have interrupted this natural “annual remodeling” of the brain and have shown that there is a direct link between the death of old neurons and their replacement by newly born ones in a living vertebrate.

The scientists introduced a chemical into one side of sparrow brains in an area that helps control singing behavior to halt apoptosis, a cell suicide program. Twenty days after introduction of the hormones the researchers found that there were 48 percent fewer new neurons than there were in the side of the brain that did not receive the cell suicide inhibitor.

“This is the first demonstration that if you decrease apoptosis you also decrease the number of new brain cells in a live animal. The next step is to understand this process at the molecular level,” said Eliot Brenowitz, a UW professor of psychology and biology and co-author of a new study. His co-author is Christopher Thompson, who earned his doctorate at the UW and is now at the Free University of Berlin.

“The seasonal hormonal drop in birds may mimic what is an age-related drop in human hormone levels. Here we have a bird model that is natural and maybe similar genes have a similar function in humans with degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, as well as strokes, which are associated with neuron death.”

The research involved Gambel’s white-crowned sparrows, a songbird subspecies that winters in California and migrates to Alaska in the spring and summer to breed and raise its young. The sparrow’s brain regions, including one called the HVC, which control learned song behavior in males, expand and shrink seasonally. Thompson and Brenowitz previously found that neurons in the HVC begin dying within four days hours after the steroid hormone testosterone is withdrawn from the bird’s brains. Thousands of neurons died over this time.

In the new work, the UW researchers received federal and state permission to capture 10 of the sparrows in Eastern Washington at the end of the breeding season. After housing the birds for three months, they castrated the sparrows and then artificially brought them to breeding condition by implanting testosterone and housing them under the same long-day lighting conditions that they would naturally be exposed to in Alaska. This induced full growth of the song control system in the birds’ brains.

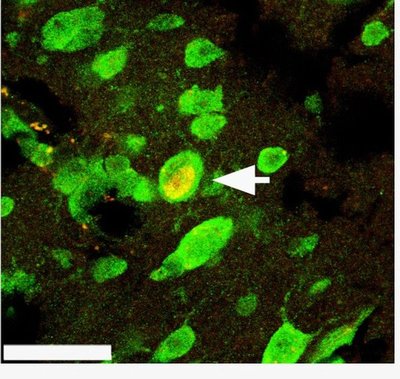

Next the researchers transitioned the birds to a non-breeding condition by reducing the amount of light they were exposed to and removing the implanted testosterone. They infused the HVC on one side of the brain with chemicals, called caspase inhibitors, that block apoptosis, and two chemical markers that highlight mature and new neurons. Twenty days later the birds were euthanized and sections of their brains were examined under a microscope.

These procedures were done with the approval of the UW’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the National Institute of Mental Health. The latter funded the research.

The HVC straddles both hemispheres of the brain but the two sides are not directly connected. When Thompson counted the number of newly born neurons that had migrated to the HVC, he found only several hundred of them among the hundreds of thousands of mature neurons he examined. And there were nearly half the number of new neurons in the side of the HVC where brain cell death was inhibited compared with the other, untreated side of the HVC.

“This shows there is some direct link between the death of old neurons and the addition of new cells that were born elsewhere in the brain and have migrated,” said Brenowitz. “What allows new cells to be incorporated into the brain is the big question. This is particularly true on a molecular level where we want to know what is the connection between cell death and neurogenesis and which genes are responsible.”

The paper was published in a recent issue of the Journal of Neuroscience.

###

For more information, contact Brenowitz at 206-543-8534 or eliotb@u.washington.edu