May 27, 2010

Ultraviolet radiation not culprit killing amphibians, research shows

In nature, ultraviolet radiation from sunlight is not the amphibian killer scientists once suspected.

Naturally occurring murky water and females who choose to lay their eggs in the shade keep embryos of one of the nation’s most UV-sensitive amphibian species out of harm’s way most of the time, new research shows. Less than 2 percent of the embryos of the long-toed salamander received lethal doses of UV in 22 breeding sites across nearly 8 square miles (20 square kilometers) in Washington state’s Olympic National Park.

For a second amphibian, the Cascades frog — known to be among the least UV-sensitive Pacific Northwest species — the researchers found no instances where eggs received lethal doses.

Declines in amphibian populations around the globe remain a real concern, but the cause is not increasing UV radiation, according to Wendy Palen, lead author and a Simon Fraser University ecologist who conducted the research while earning her doctorate from the UW, and Daniel Schindler, UW professor of aquatic and fishery sciences. The work is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and is available online.

“These findings don’t contest hundreds of studies demonstrating the harmful effects of UV radiation for many organisms, including humans,” Palen says. “Rather, it points out the need to understand where and when it is harmful.”

Papers published in the late 1990s and early 2000s raised the alarm that UV exposure was triggering amphibian declines, with many of the findings based on Pacific Northwest amphibians. Previous research wasn’t wrong: some species proved extremely sensitive to UV radiation — with especially high mortality for eggs and larvae — as shown in physiological studies done mostly in highly controlled laboratory experiments or at just one or two natural ponds or sites, Palen says.

But conditions in labs or a few isolated sites are not what the animals typically encounter in the wild and they do not behave in labs as they do in their natural habitat, the new study of a large number of breeding sites, 22 altogether, revealed.

“When simple tests of species physiology are interpreted outside of the animal’s natural environment, we often come to the wrong conclusions,” Palen says.

For one thing there are lots of “natural sunscreens” in the water. They are in the form of dissolved organic matter — remnants of leaves and other matter from wetlands and terrestrial areas that are dissolved in the water, much like tea dissolved in a mug of water. The more dissolved organic matter, the less UV exposure.

And in places where the water is crystal clear, the females from the susceptible salamander behaved differently.

“There hasn’t been a lot of work on whether organisms are capable of sensing UV intensity, but these salamanders certainly do,” Schindler says. “They change their behavior, with the females laying their eggs in the shade when the clarity of the water puts their eggs at risk.”

If for some reason UV radiation were to become much more intense, it could reach a point where amphibians can’t behave in ways that protect them, Palen says. But the restrictions on the use of ozone-depleting chemicals, under what’s called the Montreal Protocol, appear to be helping restore the ozone layer, which filters the amount of UV radiation reaching Earth.

“By critically evaluating what appear to be threats to ecosystems, we can refine our research and conservation priorities and move onto those that will make a difference in helping amphibians survive,” Palen says.

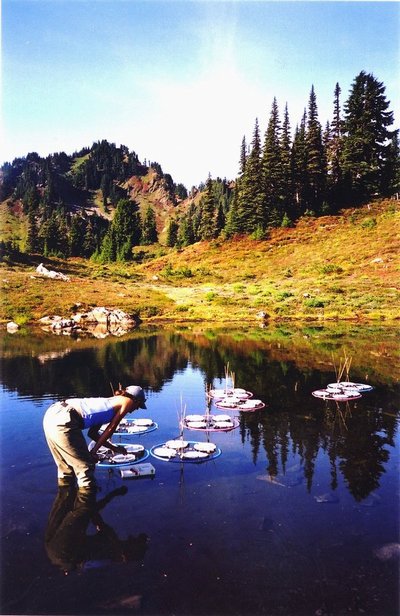

The study area includes one of the richest amphibian habitats in northwest Washington’s Olympic National Park. The work was conducted in the Seven Lakes Basin of the Sol Duc drainage in subalpine terrain, that is, on mountain sides just at the point trees struggle to grow.

Palen and Schindler intentionally looked at the most-sensitive species that has been tested from the region, the long-toed salamander or Ambystoma macrodactylum, and the least sensitive, the Cascade frog or Rana cascadae.

The 4-inch long salamander is black with a bright yellow stripe down its back and gets its name because each of its back feet has a toe that is long compared to the others. On the West Coast, it’s found from Central California to Southeast Alaska. Like most salamanders, it lives its adult life on land but needs water to reproduce. The Cascades frog, 2- to 3-inches long, is brown with black spots and a black mask like a raccoon. It’s the most common frog found in waterways at sub-alpine elevations from Northern California to the Canadian border.

The work was supported by the U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. National Park Service, Canon National Park Science Scholars program and the UW Department of Biology.