August 19, 2010

A different, greener way of making things — call it ‘humblefacture’

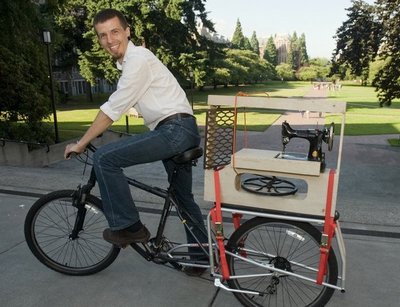

Dominic Muren will go to the U District Farmers Market Aug. 21 on a bicycle towing a sewing machine. While there, he’ll use scrap materials to create shopping bags that he will give away to anyone who can give him a source for more scrap materials.

Why, you might ask, would the lecturer in the UW School of Art’s Industrial Design Program want to do such a thing? Well, it’s all part of Muren’s passion for localizing the production of goods.

“A lot of the problems we have today come out of the way we make stuff,” Muren said. “So we have social issues like child labor and instability of local economies. We have environmental issues like pollution and the amount of plastic in the oceans. And we also have political issues, like the stability of countries or the stability of economies, and it all comes down to how things are made. I think that by choosing a different way of making things, we can address all these problems and can also get to some other things that modern manufacturing doesn’t even start to address.”

Making a few shopping bags out of fabric scraps won’t solve all these problems, of course, but the project — carried out with a grant from the local arts organization 4Culture — does illustrate some of the things Muren believes are the wave of the future: He’s using local, recycled materials; he’s transporting goods on a human-powered bicycle; he’s making a product for a particular individual as part of a face-to-face interaction with that person. Moreover, the parts of this project, which he calls “The Production Cycle,” are readily available.

The sewing machine is a Singer featherweight with a 15 series treadle and drive wheel that are stock and available on eBay. The featherweight requires an adapter collet (a metal band or ring) for a better hand wheel, and this part is available for download from Thingiverse.com. The bike extension that carries the sewing machine is available from Xtracycle.com. And the plywood parts that anchor the sewing machine to the bike both when the machine is being carried and when it’s in use (see photo) are available in plans on Thingiverse.com.

“So anyone around the world can take this design and create his or her own ‘factory’ and ride around producing goods,” Muren said.

He calls this process “humblefacture,” a play on manufacture. If more goods were made via this process, he contends, more people would be employed, goods could be produced more cheaply and with less pollution and products could be more easily tailored to the person who will use them.

The idea of Muren’s 4Culture project — he’ll be visiting three other farmers markets — is to spread the word about these ideas by talking to the people for whom he makes the shopping bags. Spreading the word is one of the things he does best, as he was chosen this year as a TED Fellow. TED is a small nonprofit devoted to “Ideas Worth Spreading.” It started out in 1984 as a conference bringing together people from three worlds: Technology, Entertainment, Design. Since then its scope has become ever broader and it now sponsors two annual conferences. The TED Fellows program is designed to bring together “young world-changers and trailblazers who have shown unusual accomplishment and exceptional courage.”

But why would an industrial designer want to turn away from industry? Maybe because he’s experienced the problems industry can cause firsthand. Muren’s first job after his undergraduate degree was at a small, independent toy invention firm, which would seem to be a designer’s dream.

“But,” he said, “the conglomeration of small toy retailers into Walmart, Target, K-Mart, and Toys-R-Us, along with the conglomeration of small toy manufacturers into Hasbro, Mattel, and Spinmaster (with a sprinkling of other small players) meant that there were fewer available shelf slots to place toys, and fewer manufacturers to license your ideas for those slots. In short, the small inventor was being squeezed, and shortly after I left to go to graduate school, the company folded.”

The experience fired his graduate studies at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, where he worked in the shop on new materials and tools to allow “garage manufacturers” to make products. And since then he’s been thinking especially about electronics, because electronics are “really really energy intensive.” To make a laptop, for example, requires 100 times the CO2 emissions required to make a kilogram of aluminum, even though aluminum is a notoriously energy-intensive material to make.

Muren’s proposal is to make electronic products modular, using a method he calls skin, skeleton, guts. To illustrate, he pulls out a watch. The guts consists of an Arduino board — an open source microcontroller with a software suite for programming it. The watch only requires one module, but the board is designed in such a way that it can easily be connected to other modules, so with different programming and more modules it could become a different product. The skeleton — the part that would enclose the face of a conventional watch —was designed and produced by Muren and consists of two pieces of plastic that snap on. He fashioned the skin — the watchband — out of leather.

The modularity, Muren explains, allows products to be more easily repaired rather than replaced, as well as modified to operate differently or morphed into new products entirely. And the fact that the designs for the pieces are open source means that anyone can open a humblefactory without a major investment or a large physical plant.

Not that everyone should engage in producing goods. “This design is not so that you can make your own watch,” Muren said. “This design is to make it easy enough so that somebody, like a tailor, who is already in your community, could start making a product that doesn’t exist in your community. That’s what I want. I would love to see a world where you went to the local x, where x was the manufacturer of whatever product you needed, and ordered up a product made specifically for you. You wouldn’t make everything yourself, but you would have a much richer existence because you would be interacting with the people who make your products.”

Where does this scenario leave industrial design, the field Muren’s students are entering?

In a fluid state, Muren said, as we move toward a world in which people think that you should sell matter and you should give away information. If someone designs something and makes the plans freely available online, and someone else uses them and makes modifications, who is the designer?

“It opens up design to more people. That’s really what’s exciting,” Muren said. “The more users you have involved in the conversation, the more appropriate the designs are.”

How will designers make money, then? That’s one of the questions seasoned designers ask Muren when he talks about his ideas.

His answer: “I don’t know. But this is going to happen. This is not something I want to make happen. This is a consequence of information availability. Because information describes objects. We’re making tools, like the 3D printer, that will allow us to transform matter with that information more and more easily. And industrial design made those tools. So we did it to ourselves. This is a more digitally informed product world. A more flexible manufacturing world is inevitable. It will happen. My job isn’t to teach students how to make this thing because they’re going to make it next year when they graduate. I need to teach them how to think this way.”